Unlike other military conflicts, the records of Forests Commission staff who served in Vietnam are not consolidated or recognised on honour boards.

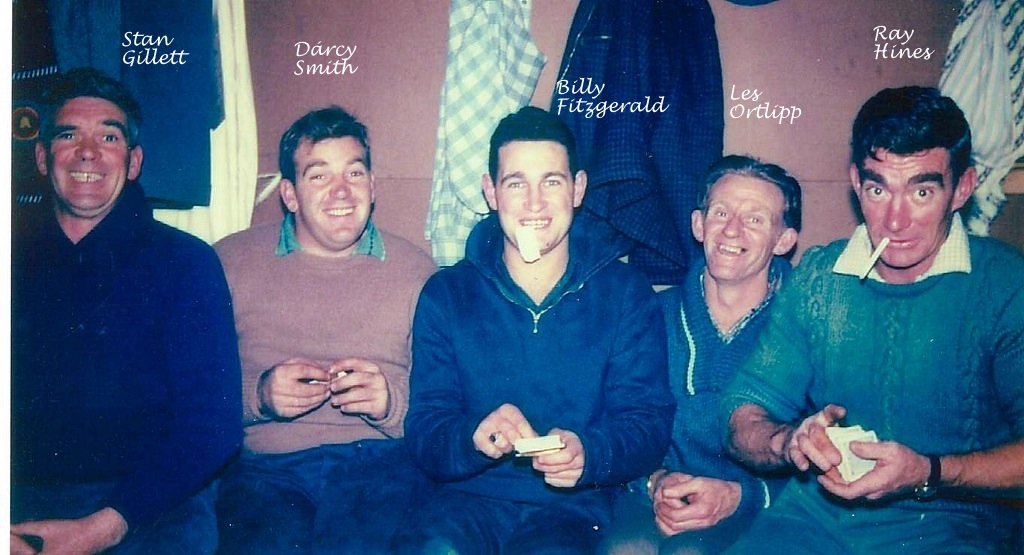

I know a few names…

One of the most notable was Des Collins who worked on the crew at Daylesford and was killed along with his workmate, Alan Lynch, at the Greendale fire on Saturday 8 January 1983.

Des had never really travelled far from Daylesford until he was conscripted into National Service in September 1965.

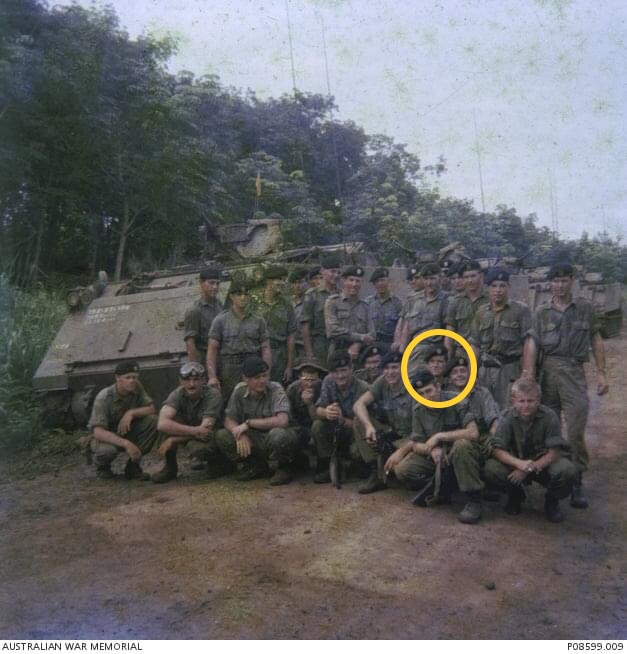

Sent to nearby Puckapunyal, Des completed his basic recruit training before being posted as Trooper (3787452) to the newly formed 1st Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron (1 APC Sqn).

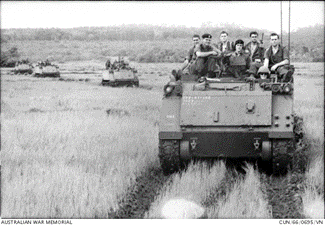

Des trained as a driver of an M113 Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC), and in May 1966 sailed on the HMAS Sydney to South Vietnam to join the 1st Australian Task Force at Nui Dat.

Upon its arrival, the first tasks for the APC squadron were to secure the new base by erecting defences and keeping the road between Vung Tau, on the coast, and Saigon open.

Because there were so few APCs at Nui Dat, the squadron was constantly busy supporting infantry, fire support, reconnaissance, cavalry roles, offensive manoeuvres against enemy positions, troop transport, moving equipment, towing artillery guns and casualty evacuation.

The squadron’s most notable battle was on 18 August 1966 to transport soldiers from A Company to relieve 108 soldiers of D Company holding out against overwhelming odds of about 2500 Vietcong, in the pouring rain, in a rubber plantation at Long Tan.

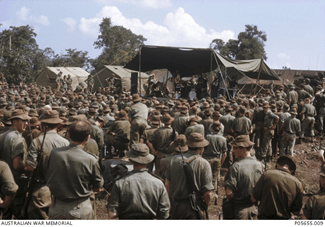

The day was supposed to be relaxing for the troops at Nui Dat with a concert by entertainers Little Pattie and Col Joye.

An artillery barrage began around mid-day on enemy positions 2.5 km away while RAAF helicopters flew over the beleaguered solders of D Company to resupply them with ammunition.

The rain became very heavy as Des Collins rumbled his APC out through the wire surrounding the base around 6 pm. It was a typical tropical downpour, but it muffled the noise of the engines and squeaking of the tracks which confused and surprised the Vietcong.

On arrival on the battlefield across the soggy rice paddies and flooded creeks, the APCs fanned out to make a sweep through enemy lines where they inflicted heavy casualties, before the Vietcong broke off and melted back into the jungle.

The battle ended and the monsoonal storm abated, as suddenly as both began. Under cover of darkness, the Australian units withdrew and regrouped while the dead and wounded were evacuated by helicopters. Soldiers spent a restless night as artillery and air strikes continued to pound the battle site and likely enemy withdrawal routes.

The next morning, a combined force of infantry and armoured personnel carriers went back into the battlefield to conduct a thorough clearance.

The Australians lost 18 men killed and 24 wounded. One of those killed was from 1st APC Sqn, and for their actions, three men from the squadron received gallantry awards.

After spending 12 months overseas in Vietnam, Des was honourably discharged in September 1967 and returned home to Daylesford. Like many other veterans, Des rarely spoke of his experiences.

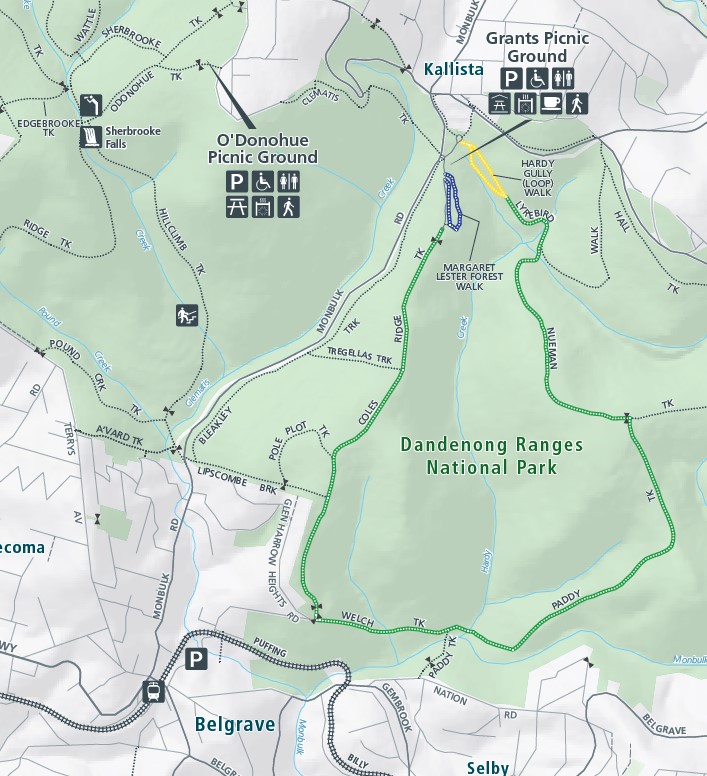

Des remained an active member of the local football club, playing and then coaching juniors. He was also a member of the Daylesford RSL and CFA.

Around 1969, Des got a job on the crew with the Forests Commission at Daylesford, a job he loved.

One of his good friends was Alan Lynch, who also worked for the Commission on the crew, and they often walked to work together.

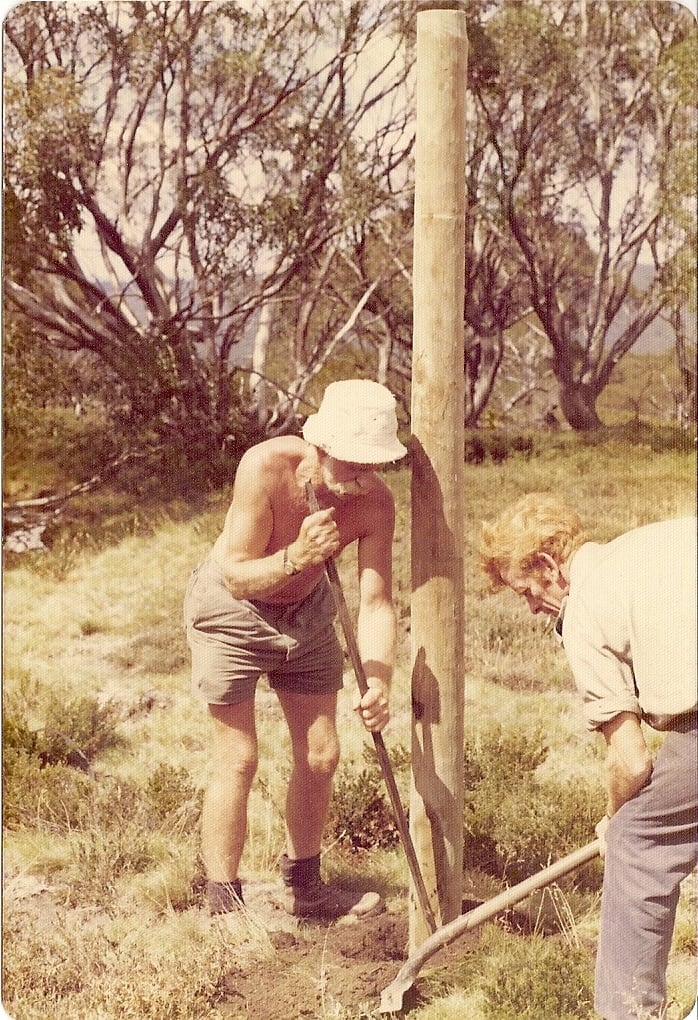

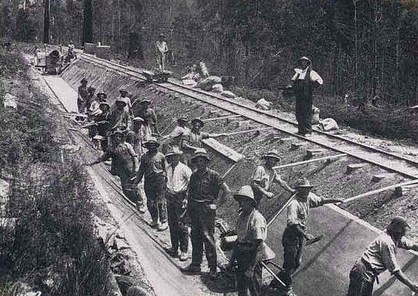

Both Alan and Des had many practical bush skills including roadbuilding, firefighting and driving heavy machinery.

But their tragic deaths in a bushfire at Greendale when their machine was overrun by fire were somewhat overshadowed by the major Ash Wednesday bushfires of 16 February 1983 only a few weeks later.

A 40th anniversary memorial service was held for the two men earlier this year.

https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/stories/national-service-1951-1972