The timber industry in Victoria was arguably very lopsided with the Forests Commission, as a large government-owned monopoly, controlling forest licencing, allocation and supply of timber to sawmillers.

In most cases the relationship between sawmillers and the local District Forester were cordial and business like, but it was clearly an uneven one at times.

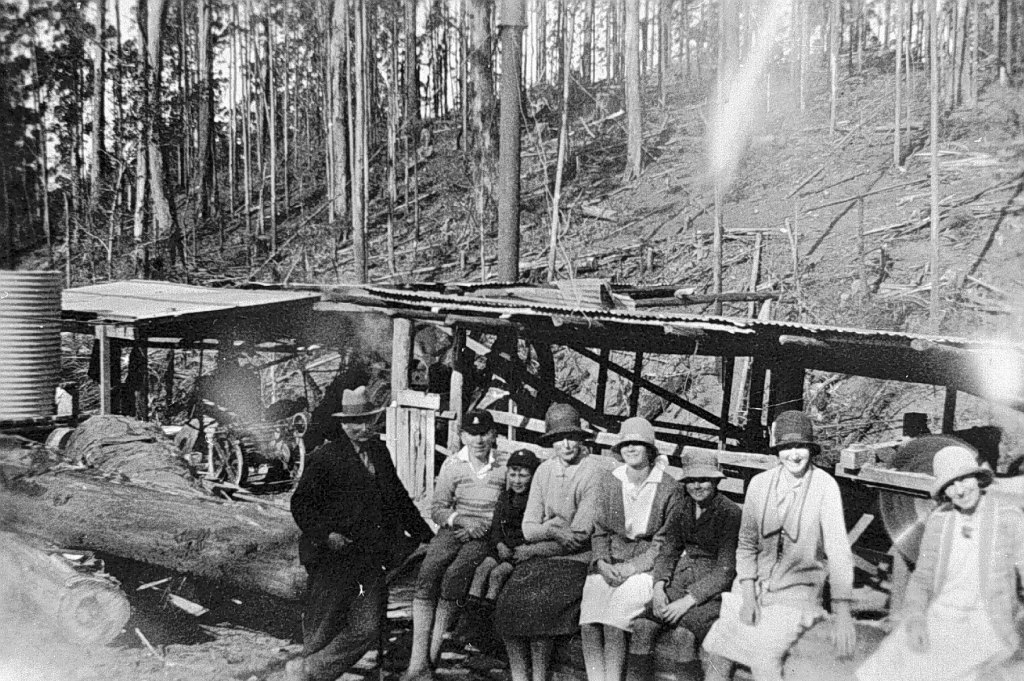

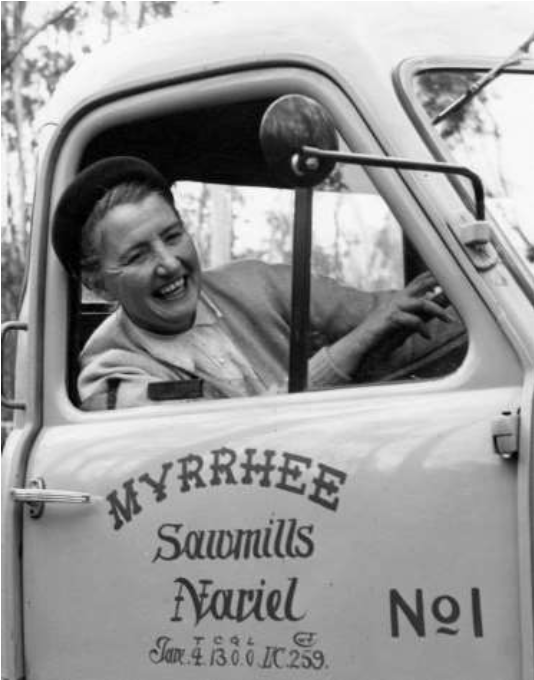

It’s also fair to say that sawmilling in Victoria was primarily a male domain. Women were involved, but they tended to play a lesser role in the business.

Julia Marion Harvey Hale grew to become a formidable legend in Victorian forestry and sawmilling circles and was not going to be intimidated by mere District Foresters, or even the Commissioners.

Born in 1907 in South Australia, Julia became involved in several sawmilling enterprises in northeast Victoria, the first being with a 25% holding in a small mill on the tablelands south of Whitfield in 1936. Her business partner, Arthur Dye, originally came from Gembrook, but the arrangement was short-lived with the sale of the mill in 1937.

Undeterred, Julia Hale formed another business partnership in 1936 with sawmiller James Moore which proved more successful. Moore had ten years’ experience in the Gembrook district, and they started Myrrhee sawmills on Fifteen Mile Creek, north-west of the earlier Tablelands Sawmil in August 1936 to cut timber off private property.

Moore ran the sawmill while Hale the controlling partner oversaw the sales, marketing and financial side of the business. In May 1938, the mill was moved to a new cutting area on State Forest and the company purchased its first crawler tractor, but the forest was steep and rocky making the mill barely profitable.

Meanwhile, Julia became involved with her father and a consortium of others in a murky scheme to buy 6000 acres of forested Crown Land in Tasmania. Normally, the sale would have been refused because of the standing timber, but it was approved in 1938 following the alleged intervention by the Tasmanian Minister for Forests, Robert Cosgrove. This transaction, and several others like it, led to a Royal Commission into forestry administration in 1945. One of the key recommendations was the formation of the Forestry Commission of Tasmania, based upon the Victorian model.

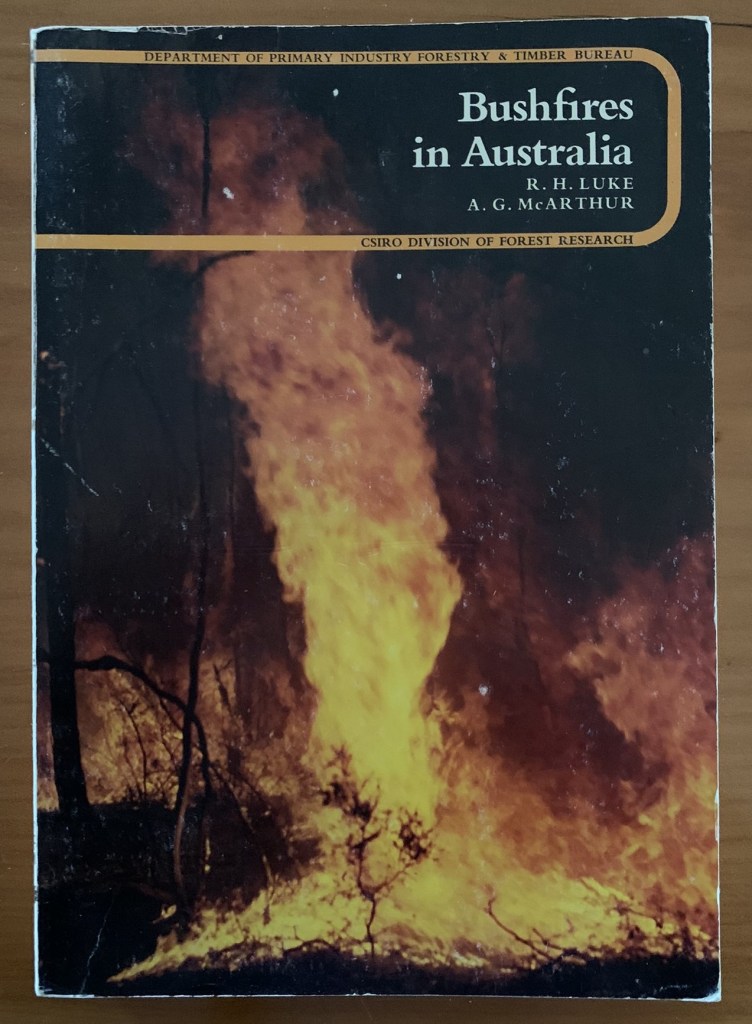

The Black Friday bushfires of 1939 forced an urgent need for timber salvage in the Central Highlands and led to a major shift for the entire Victorian timber industry.

Julia Hale acted quickly, and on 20 February 1939 while the bushfire smoke was still swirling and the Stretton Royal Commission had begun, she lodged an application with the Forests Commission for a 1000-acre allocation at the head of the West Tanjil River north of Noojee. The mill was up and running by January 1940, but constructing access to the mill by either roads or tramways remained a major impediment.

Julia then applied in December 1939 for a second logging area just over the ridge from the first mill in the headwaters of the Thomson River to access fire killed mountain ash, shining gum and woollybutt.

But financial pressures on her ventures were starting to show, so she applied to the Commission for a salvage loan of £1000. But other setbacks, combined with the realignment and slow construction of access roads hurt her bottom line and Julia’s crawler tractor, valued at £2000, was offered as security of this and other loans.

At the time, the mill was supplying sawn timber to the Commission’s seasoning works at Newport, so loan repayments were deducted from the amount paid for the timber.

But Julia’s misfortune didn’t stop there. A major labour shortage caused by the war was made worse by the remoteness of the mill, so a boarding house was built in the hope of attracting enough labour to run her operations. More loans were made, but snow and winter road closures combined with a continuing shortage of labour led to the closure of the No.1 mill in May 1942.

Meanwhile, a new mill was established at Nariel, just south of Corryong, in 1946 to access large stands of high quality old-growth wollybutt near Mount Pinnibar.

The Commission controlled the first section of the road construction and her licence agreement required Julia to extend the logging road at her own cost. But by February 1947, Julia Hale was again in financial difficulties, and she approached the Minister of Forests, Bill Barry, for assistance by getting the Commission pay her to construct the road as a contractor.

In January 1948, W. E. Flanigan applied to the Commission for a logging area in the headwaters of Emu Creek near Milawa. It became apparent to the Commission that Julia Hale was providing the money and was the major partner in the new enterprise. Flanigan later sold his share to Julia and retired in 1950, but the Emu Valley mill burnt down in June 1951.

It was around this time that Forests Commission officers began to have serious reservations about the viability of Julia Hale’s logging and sawmilling operations in both the Central Highlands and Myree. This led to growing concerns about the security of the loans it had made to Julia.

By 1953, the Commission believed that there was a significant sum of money still owing on her loans due to short deliveries of timber to the Newport seasoning works, but Julia considered the total debt had been repaid. The relationship was far from cordial and a series of savage letters was exchanged. But in 1961, the Commission wrote-off the debt. There seems little doubt that poor record keeping and accounting methods by the Commission had contributed to the discrepancy. However, the fallout from the quarrel caused untold and ongoing friction between Julia Hale and the Forests Commission.

But the mill at Nariel finally made Julia prosperous. The post-war boom was in full swing, and the mill had secured some valuable supply contracts.

Julia Hale was in her early forties and in the prime of her life. She made regular visits to the Nariel mill in her white “Silver Cloud” Rolls Royce from her substantial home and farm property known as “Buckanbe”, at 32 Orion Road in Vermont.

Always expensively and fashionably dressed in English tweed skirts and silk blouses, accompanied with sensible shoes, she carried the air of the English aristocracy and was equally at home in the city or the country. While undoubtedly a tough and forthright businesswoman, Julia also took a strong interest in the welfare of her workers and their families.

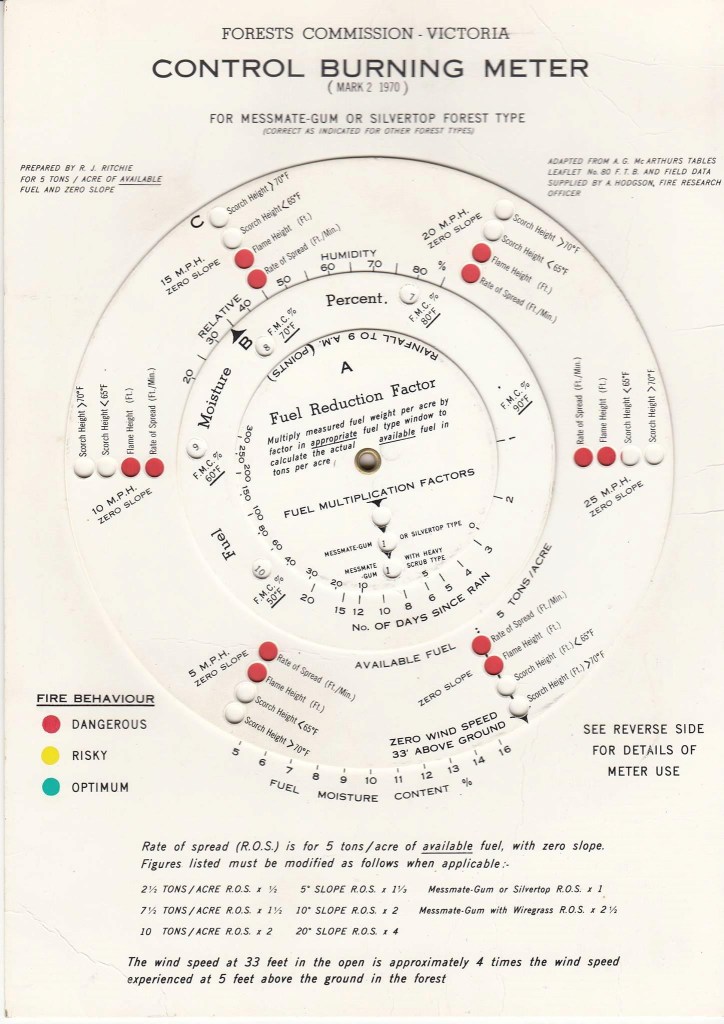

In January 1950, the Commission introduced a new royalty equation system which took account of the distance that logs were hauled from the forest to the sawmill, the standard of the forest roads, the quality and size of the logs together with the distance to central markets in Melbourne. It was intended to reduce wastage but also be simple and equitable for all sawmillers across Victoria.

But in 1952, further tension between Julia Hale and the Forests Commission surfaced over who was responsible for measuring logs and determining inputs into the Royalty Equation. The matter was escalated in 1954 to her local MP, a prominent barrister and Corryong grazier, Thomas Walter Mitchell, who was no friend of the Commission, and he raised the matter with the Premier John Caine in State Parliament.

The minor bickering escalated into a major dispute by early 1957 over Julia’s claim for a refund of royalty to the tune of £75,000, which she claimed was overpaid because of an incorrect road classification under the new royalty system. The subsequent refusal by Julia to sign a new log licence agreement led to the suspension of all harvesting and log supply by the District Forester.

By 1962, the dispute went to arbitration with hearings at Corryong. High profile and expensive lawyers were engaged but the result was a disaster for the Commission, with Julia Hale being awarded substantial compensation. An appeal by the Commission was unsuccessful, but the wound continued to fester until Julia Hale’s death from breast cancer on 19 October 1964.

From the very start, Julia Hale seems to have avoided direct dealings with her local district forester, who would have normally been the first point of contact for any sawmiller. She adopted a “take no prisoners approach” and always went straight to the top and thought nothing of lubricating important relationships with a case of Scotch whisky discreetly delivered to a home address.

It became part of Forests Commission folklore that when Julia made personal visits to the Commissioners in Head Office in Melbourne from her lavish estate in Vermont, to pay her royalty and loan debts, she deliberately parked her Rolls Royce in the Chairman’s carpark out the front. It’s also said that Julia regarded some Forests Commission officers as a bit of “sport”, and she had little tolerance for any bureaucrat who got in her way. While some senior male public servants in the Commerce Branch were said to scurry whenever she arrived in the building.

Julia never married, or had children, and in the wind-up of her estate she first provided generously for her family, including her brothers and sisters, but also for her employees.

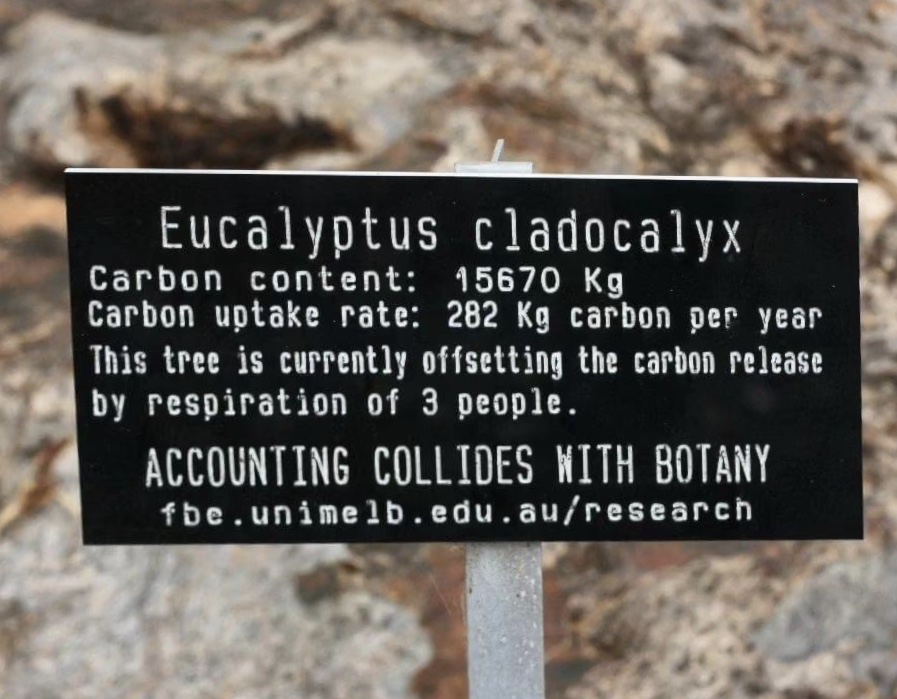

Somewhat ironically, given her long running and fractured relationship with foresters and the Forests Commission, Julia Hale directed in her will that a $1M bequest to be made to the Forestry Department at the University of Melbourne.

This is an abridged version of a more comprehensive account by Peter Evans which was presented at the ninth conference of the Australian Forest History Society at Mount Gambier in October 2015.

https://www.foresthistory.org.au/2015_conference_papers/06%20Evans%20-%20Julia%20Marion%20Harvey%20Hale%20-%20Victoria’s%20most%20prominent%20woman%20sawmiller.pdf

https://vermonthistory.weebly.com/buckanbe-park.html