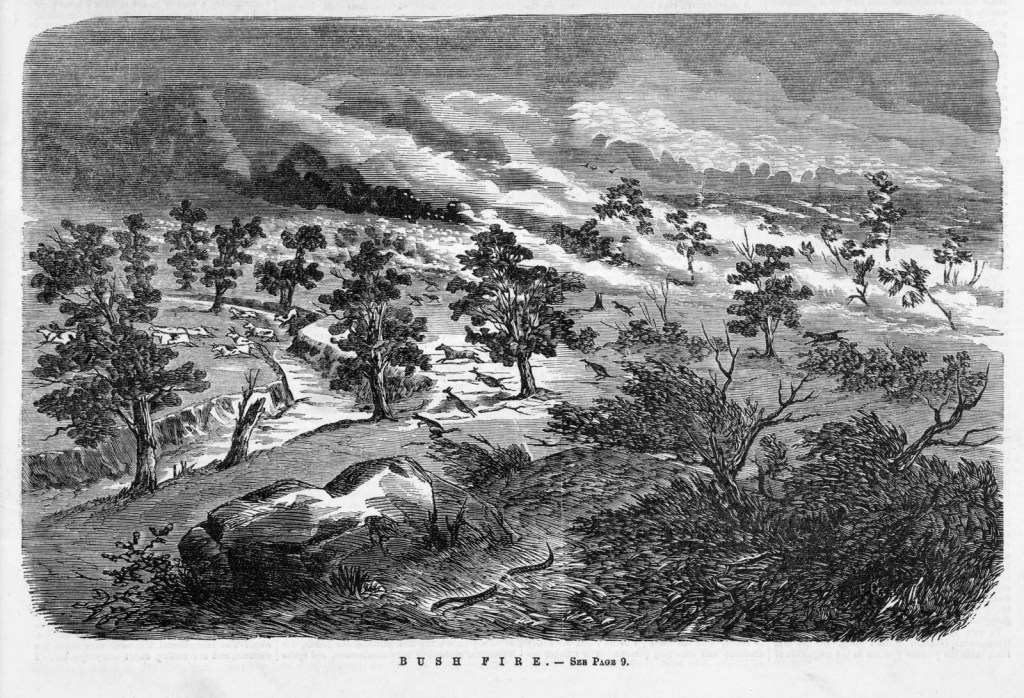

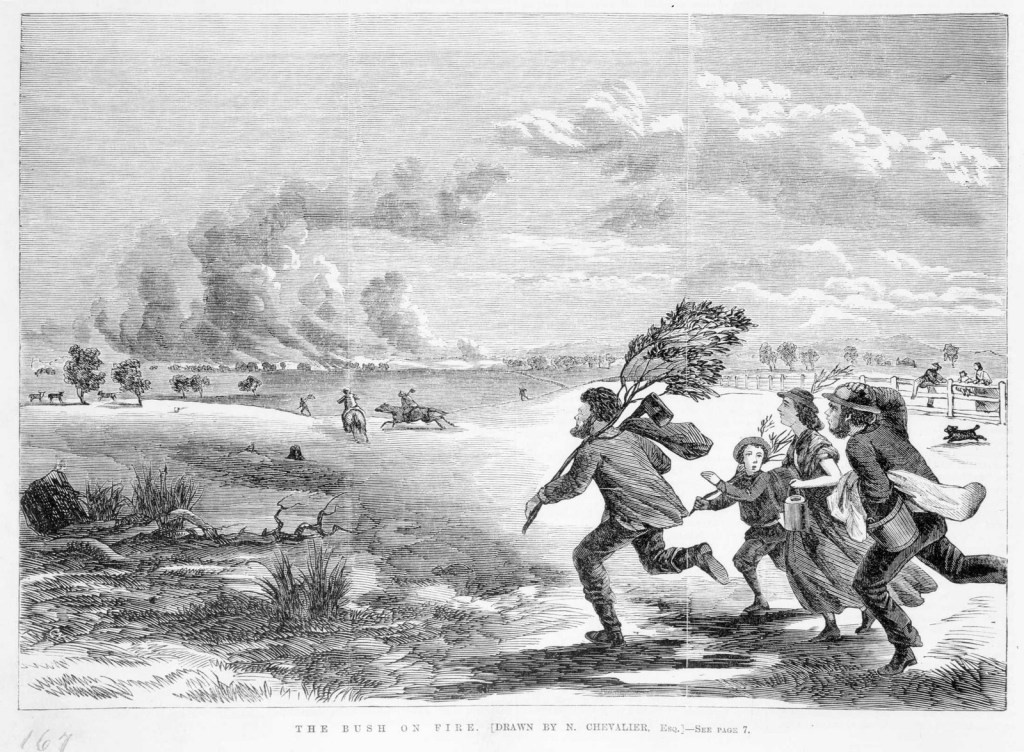

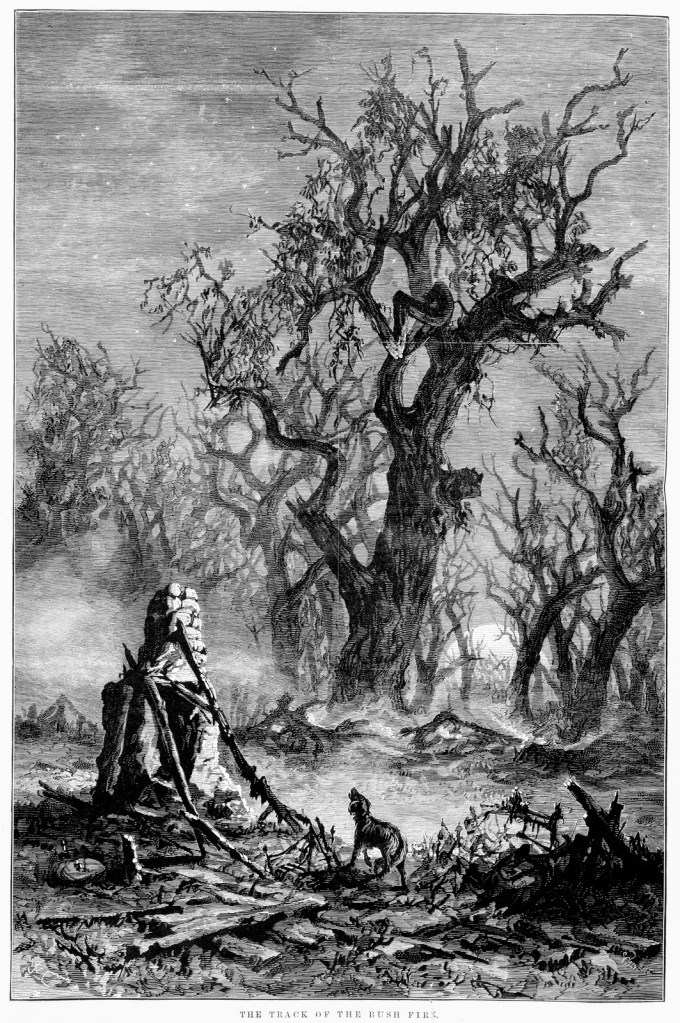

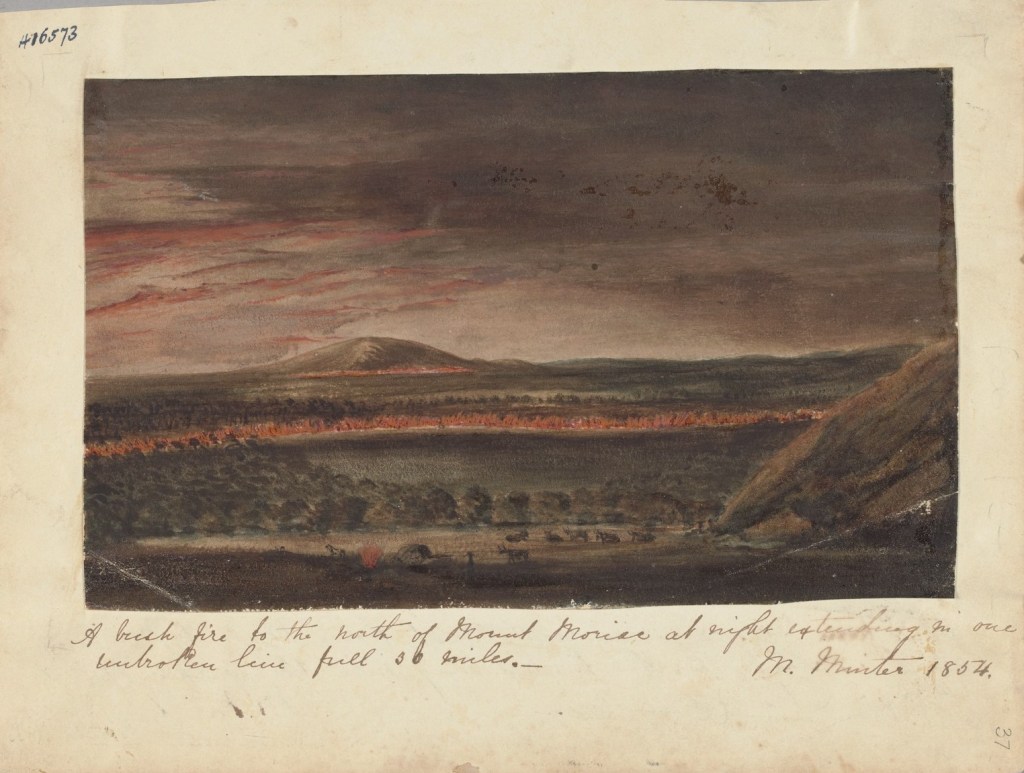

The deadly bushfires, the indiscriminate clearing of Victoria’s public land, and wastage of its forests and timber resources during the 1800s could no longer be ignored.

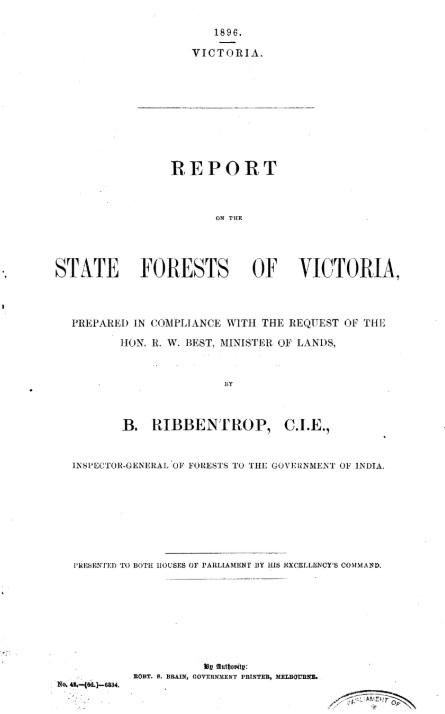

There had already been inquiries and independent reports including those from D’A. Vincent (1887), Perrin (1890) and Ribbentrop (1896) into the parlous state of Victoria’s state forests, but with little result.

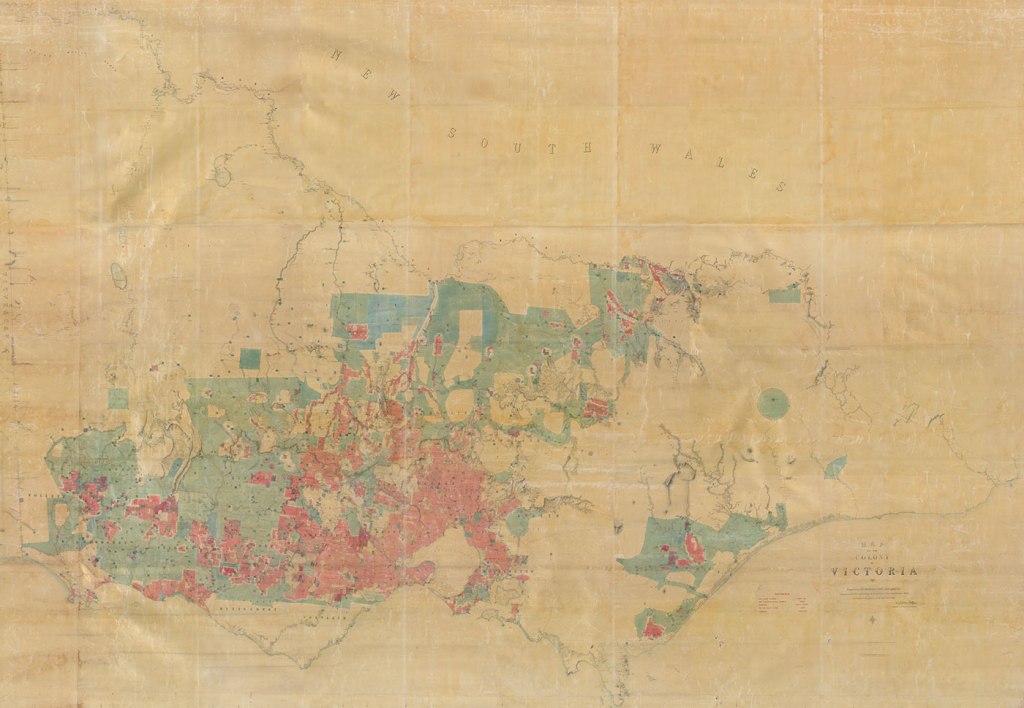

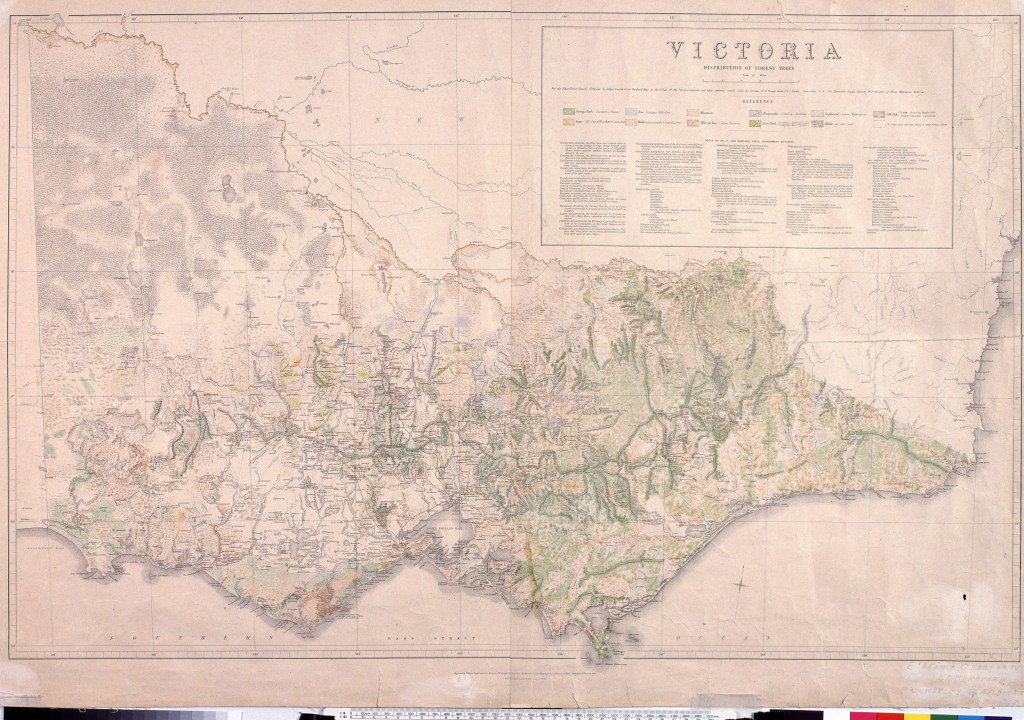

There was no shortage of information on the state of Victoria’s forests, the loss of available crown lands to mining and settlement, the eye-watering wastage of timber and the inadequacies of forest administration.

Some of the important groundwork had recently been done by Perrin, Vickery and Blackburne in their report to Parliament in early 1897 on the “Permanent Reservation of Areas for Forest Purposes in Victoria”.

In June 1897, the Minister for Lands, Sir Robert Best, finally announced a Royal Commission into “the condition of the state forests and timber resources in the colony, with the view of ascertaining if they should be more carefully conserved, and if there is a prospect of a profitable export trade”.

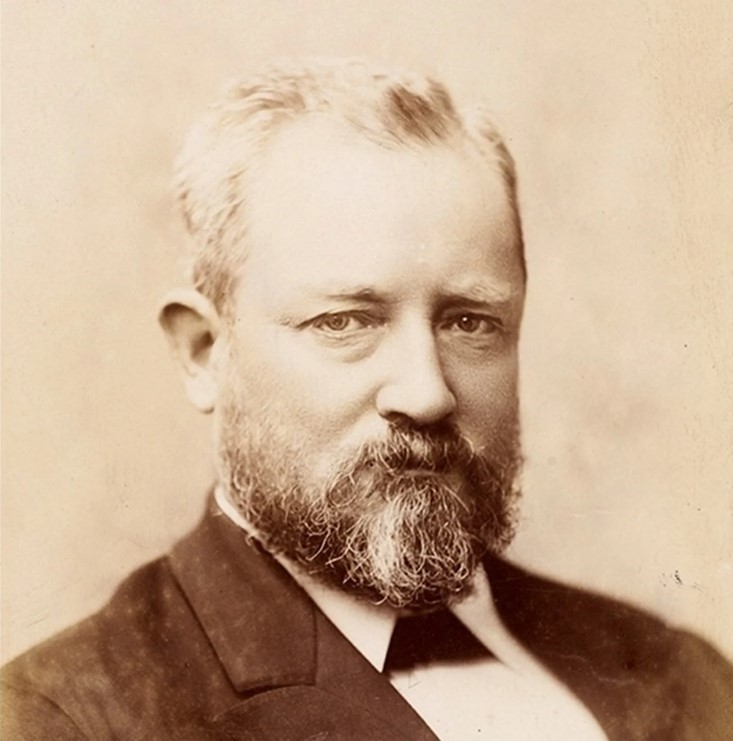

The well-respected parliamentarian, Albert Lee Tucker MLA, was appointed Chairman. He had previously been President of the Board of Land and Works and Commissioner of Crown Lands and Survey between 1883 and 1886. He was well equipped for the position because of his experience as chairman of the 1878 royal commission on closed roads and member of the 1878 commission of inquiry into crown lands.

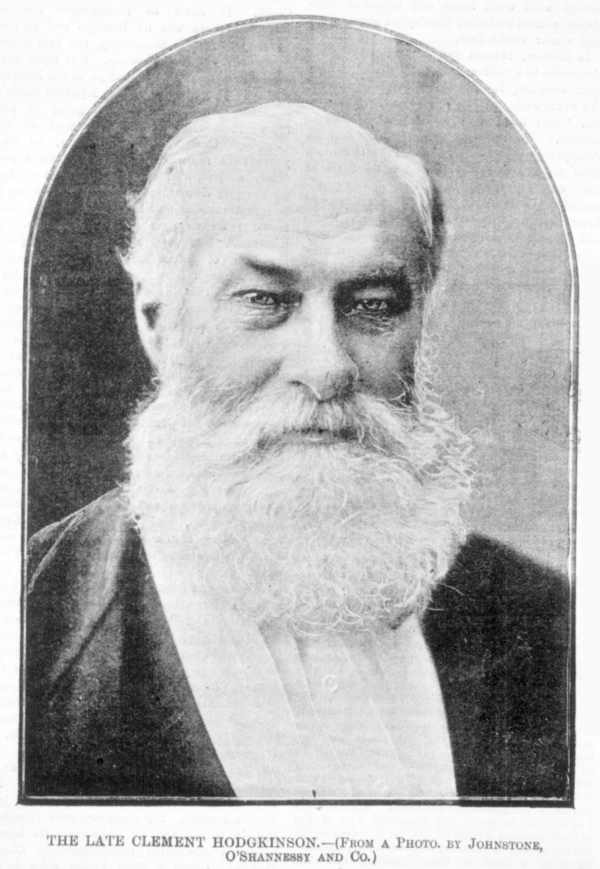

The Royal Commission consisted of ten members of Parliament, representing sawmillers, miners, woodcutters, sleeper-hewers, and settlers. The Inspector of Forests, Hugh Robert MacKay, was appointed as Secretary.

To meet its expenses, the Royal Commission was granted the sum of £150, later increased by £250. After receipt of its first progress report three further increases were made up to the magnificent sum of £800 for four years solid work.

Over its four years of sittings and public hearings across the state, the Commission completed fourteen reports (a total of 289 pages) and was working on two more before being terminated.

Under the authorship of Hugh MacKay, nine of the reports dealt with forests in specific localities, each inquiry dealing with “resources, management and control”.

One of the most damming reports was for the Wombat Forest which was considered by the Royal Commission to be a “ruined forest” because of the indiscriminate and uncontrolled cutting by miners, sawmillers, splitters and settlers. However, it was also noted as Victoria’s “most important forest” because of its immense stands of young regrowth timber, particularly messmate, stringybark, manna gum and peppermint, along with its rapid growth rate.

The other five reports focussed on a variety of themes including sleeper-hewing, forest royalties and the royalty system, fire protection in country districts, questions relating to forestry in metropolitan catchments, including Board of Works control.

The Commission’s fourteenth report outlined detailed consideration of legislation, reservations, administration and control, conservation and inspection, the protective staff, forage allowance, police patrol, working practice (including timber, improvement fellings, wattle bark, grazing, rates and charges), fixed licences, water frontages, fire protection, and technical training.

Their reports noted –

“all previous investigators who have inquired into the condition of our forests have adopted the same view”.

Their key recommendation was wresting control of the forests from ministerial influence and the powerful Lands Department and vesting them in the hands of an independent commission, to be modelled on similar bodies in Great Britain and many of the German states.

Source: Stephen Legg (1995), Debating Forestry: An Historical Geography of Forestry Policy in Victoria and South Australia, 1870 to 1939.

Royal Commission – Scope of Inquiry.

1. As to (a) state forests and timber reserves, which should be permanently reserved; (b) whether the timber reserves or any portion of them should be proclaimed state forests; (c) whether any Crown Lands in any state forest or timber reserve should be proclaimed a state forest; (d) as to which, if any, of the reservations of the areas as timber reserves or state forests should be revoked wholly or in part, and made available for selection.

2. To consider and report upon the existing system of working state forests, and as to what additional steps, if any, should be taken for the further conservation or growth of timber.

3. To report upon the existing system of licences, and particularly as to whether it is advisable to abolish wholly or in part the licensing system, and substitute there-for the royalty system.

4. To report as to whether the growth and distribution of trees to public bodies and the general public for planting should be continued, and if so on what conditions or terms such distribution should be.

5. To report as to whether any state forest or timber reserve at present inaccessible for the purpose of profitable working should be opened up.

6. To report as to whether an export trade can be established with profit, and what steps should be taken to attain that object.

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/9154474

Royal Commission on Forests – Reports.

1. 20/10/1898, 9pp.,Sleeper-hewing in Forest Reserves and on Crown Lands.

2. 8/12/1898, 9pp.,Victoria Forest: Its Resources, Management, and Control.

3. 15/3/1899, 12pp.,The Redgum Forests of Barmah and Gunbower: Their Resources, Management, and Control.

4. 27/6/1899, 14pp., Wombat Forest: Its Resources, Management, and Control.

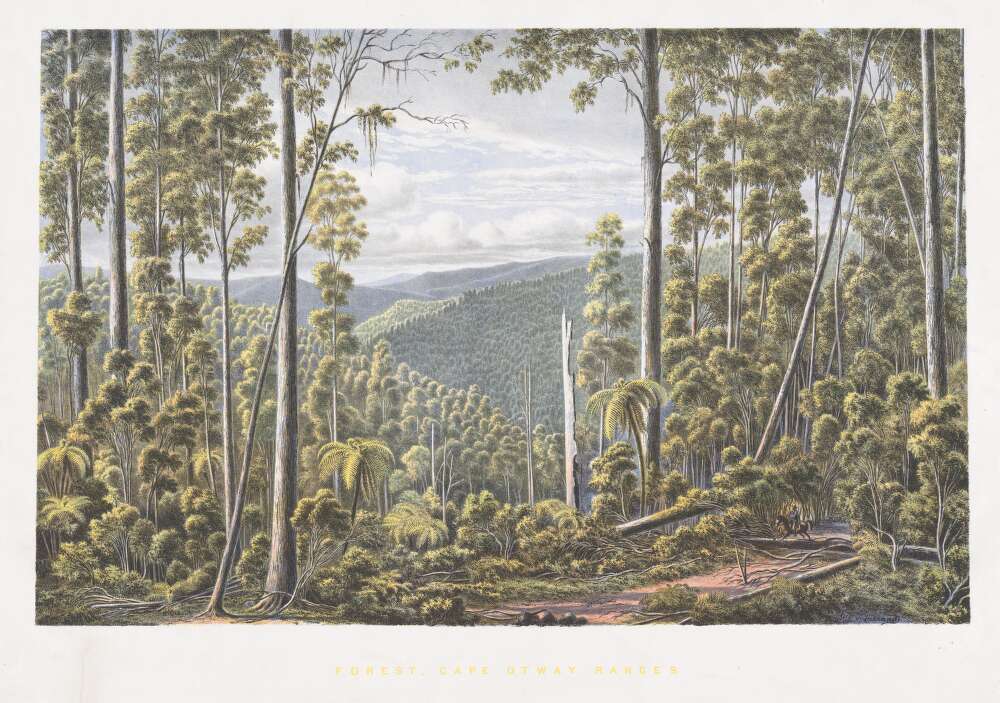

5. 23/8/1899, 16pp., The Otway Forest: Its Resources, Management, and Control.

6. 27/9/1899, 7pp., The Stanley and Chiltern Forests: Their Resources, Management, and Control.

7. 6/12/1899, 15pp., The Forests of the County of Delatite; being the King River, Winteriga, Dueran, Toorour, Toombullup, and minor reserves: Their Resources, Management, and Control.

8. 20/12/1899, 5pp., Grazing Lands in the Parishes of Wurrin, Wangarabell, Koola, and Demdang: Genoa River Forest East Gippsland.

9. 7/3/1900, 6pp., Pastoral Lands in the Parishes of Connangorach, Mockinyah, Daahl, and Tyar, County of Lowan, known as the Black Range Forest, Upper Glenelg District.

10. 20/6/1900, 21pp., Forest Royalties and the Royalty System.

11. 18/7/1900, 26pp., Fire Protection in Country Districts: Being a report on the measures necessary to prevent the careless use of fire or the spread of bush or grass fires on public and private lands.

12. 18/9/1900, 12pp., The Pyrenees and Minor Kara Kara Reserves, North Western District, and Tambo Reserves, North Western District, and Tambo Reserves, East Gippsland; with a short review of the work of the commission.

13. 10/10/1900, 36pp., Proposed Diversion of Water from Upper Acheron for Supply of Metropolis, and question of vesting catchment area in Metropolitan Board of Works.

14. 7/3/1901, 101 pp., Forestry in Victoria, Australia. The Legislation, Control and Management requisite; with some account of the Forest Resources of the other Colonies of Australasia, and of Forestry in other Countries.

Proposed Forest Bill – 1901.

The Royal Commission in its 14th Report of March 1901 developed a proposal for Forests Bill but it was not implemented due to delays in Parliament and lack of political support.

1. Independent control of the forest reserves, and the withdrawal of the administration from the Lands Department.

2. The dedication in perpetuity of “Reserved forests”, which term will include all permanent reserves for the growth of timber, or for climatic reasons, or for both purposes.

3. The dedication for an indefinite period of “Timber reserves”, being as a rule small areas useful for mining timber, fencing material, and fuel, and for their reduction in area or abolition, on a resolution of both Houses of Parliament only.

4. The control of “Protected forests” which term will include all unreserved mountain timber lands, and, generally, all unoccupied Crown lands, or public lands occupied for grazing or other purposes by persons having no claim to the fee-simple thereof.

5. The reasonable protection of all timber, scrub, or brushwood growing along the banks, or at the sources of rivers and streams; along the shores of lakes, lagoons, and other bodies of fresh water; on sea-coasts, or along the shores of bays, estuaries, and other inlets of the sea; on drift sands, or sand hills and ridges, or on the public roads.

6. The protection from wanton injury or damage of all exotics or indigenous trees planted on public or private lands, on public or municipal reserves, or on streets, roads, or lanes.

7. The demarcation on the ground of all “Reserved forests” which have hitherto not been surveyed within a fixed period.

8. The protection of the reserves and Crown lands from the misuse or careless use of fire.

9. The encouragement of tree-planting in bare districts.

10. The encouragement of persons who protect and maintain on their freehold lands, or on lands in course of alienation from the Crown, a fixed proportion of indigenous trees useful for timber and shade purposes.

Source: Royal Commission on Forests, 14th report.