The declaration of a Total Fire Ban (TFB) in Victoria was for many years the key indicator of a day of extreme fire danger for both the fire agencies and the public. But it also served, and indeed continues, to prohibit a range of activities well beyond a ban on barbeques and burning off.

Total Fire Bans have been around for many years but their origins, naming and application have changed since the first “ban” was applied under the County Fire Authority Act 1944. Originally, the term “total fire ban” was not even used, although this was in effect what was imposed. Instead, warnings and prohibitions were issued about “acute fire danger” days.

Prior to the CFA Act, restrictions upon the use of fire were largely contained in the Forests Act 1927 and these extended beyond the public estate and onto private lands. The Bush Fire Brigades Act 1933 was silent on the matter.

During World War 2, after the disastrous 1939 bushfires but before those of 1944 which spurred on the creation of the CFA, the Government used the provisions of the wartime national security regulations to institute a Rural Fire Prevention Order to provide for the prohibition of the use of fire in rural areas during times of high risk. Originally aimed to deal with enemy action resulting in fire, it was later used as a general fire prevention measure.

The creation of the CFA shifted responsibility for restrictions on fire in the country area of Victoria outside public lands to the new authority. The provision for restrictions on the use of fire during the summer period largely replicated the terms and penalties of the Forests Act in relation to burning off. Clause 41 of the Country Fire Authority Bill 1944 contained provisions in relation to “days of acute fire danger”, on which no fires would be allowed.

In speaking to the bill in the Legislative Council, the responsible minister Hon. Gilbert Chandler pointed out that warnings of days of acute fire danger would be “made available by means of radio broadcasts and through the medium of the police”. A major point of contention around the new law related to its impact upon gas-producers – the charcoal burners in use on vehicles as an austerity measure to save fuel during the war. Their use was to be banned on acute fire danger days. The penalties for lighting a fire in country Victoria in contravention of the new law were the same as under the forests legislation: a fine of up to £200 or two-years imprisonment.

As late as 1959, the Country Fire Authority Service Manual issued to personnel referred to the “important provision of the ‘Acute Fire Danger Day‘”, pointing out that when news of this was broadcast “no fires may be lit or maintained in the open air at all”.

The manual stated: “In practice, whenever possible, the warnings of such days (with a clear explanation) are given at the conclusion of the 7 o’clock news session over the National stations the previous day and are repeated at intervals.”

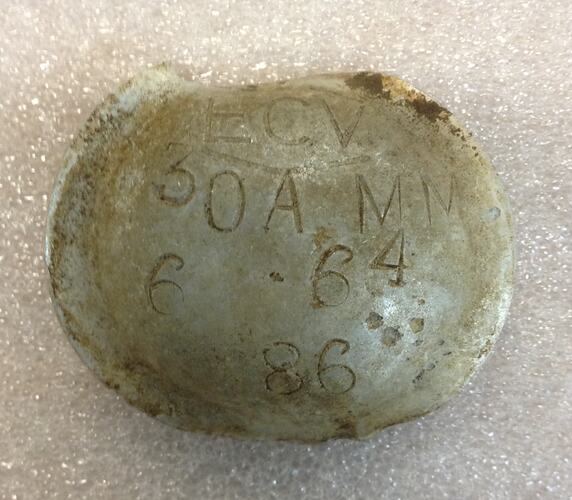

In Victoria, the term “total fire ban” did not come into common use until the mid-1960s. In other states, notably South Australia’, the term “total fire ban” had been in use from the late 1950s and in the early 1960s there was reference to “total bans” in New South Wales. (Interestingly, NSW fire personnel still use the term “To-Ban” [pr. “tow-ban”], whereas in Victoria “TFB” is the more common short version).

By 1965, the term was being used in official communications. The 1966 Victorian Government publication Summer Peril, introduced by an avuncular-looking Sir Henry Bolte, talked about the CFA “Summer Periods” and Forests Commission “Prohibited Periods” and placed Total Fire Bans firmly on the agenda.

“On certain days, when the fire danger is extremely high, the lighting of fires may be totally prohibited,” the booklet stated. “Always watch for this warning – Total Fire Ban To-day”. It went on to explain that the warning would be given over the radio, television and in the press and would usually apply to the whole state, including forest, country and metropolitan areas.

“The ban includes incinerators, barbecues, out-door cooking appliances of all types, including L.P. gas appliances and camp and picnic fires, and burning off for which a permit has previously been obtained.”

Broadcast warnings in the 1960s and 1970s were given in multiple languages. (My father, a German language broadcaster, was among those who did the foreign language voiceovers.)

Until 1985, Total Fire Bans were imposed for the whole of Victoria, a measure seen in some quarters as sensible given the relatively small size of the state. The bans have since been applied to the whole state or to specific fire weather districts, based upon fire weather conditions determined by the Bureau of Meteorology.

Legislation took a little while to catch up with common usage. It was not until 1974 that the words “a warning of the likelihood of the occurrence of weather conditions conducive to the spread of fires” in the CFA Act were replaced by “a declaration of a day of total fire ban”. And it was not until 1983 that section 40 (the original clause 41) was replaced altogether with a new section, ‘Provisions about total fire bans’, which stated: “The Authority may when it thinks fit declare a day or partial day of total fire ban in respect of the whole or any part or parts of Victoria and may at any time amend or revoke such a declaration.”

The declaration of a Total Fire Ban has many consequences, particularly for industry as the range of activities prohibited expanded, while some such as the use of gas barbecues have been modified. A TFB became an important “trigger for action” for community members in making decisions about whether to stay and defend property or leave early.

Determined in consultation with the operational leaders of the other Victorian fire agencies, the TFB in time became the most significant and readily understood indicator of fire danger across all land tenures, both private and public.

However, the significance of TFBs was diminished to some extent by the national fire danger ratings system which came into play after the 2009 Victorian bushfires. The new rating of Code Red (or Catastrophic, as it was in every other state) was confusing to many Victorians who then saw this as their trigger for action, even though it foretold of fire weather conditions far worse than those required for a TFB declaration. Hopefully, the 2022 revision of the national ratings (Victoria has now adopted Catastrophic in line with the rest of the country) and its accompanying campaign will clarify matters.

The declaration of a Total Fire Ban remains crucially important in reducing the potential source of fire ignitions on days of extreme danger and as a trigger point for decision-making and action by the public.

A database of all “total fire ban days” since 1945 is maintained on the CFA website

By John Schauble

Footnote: the 84/85 season was the last for ‘whole of state’ only for TFB. For 85/86 the state was divided into 5 TFB districts – North West, South West, Central (which included Melb & Geelong), North East and Gippsland.

It was in Nov 2010 when it changed to the present nine TFB districts and some BOM forecast district boundaries were slightly altered so that TFB and forecast more generally aligned.