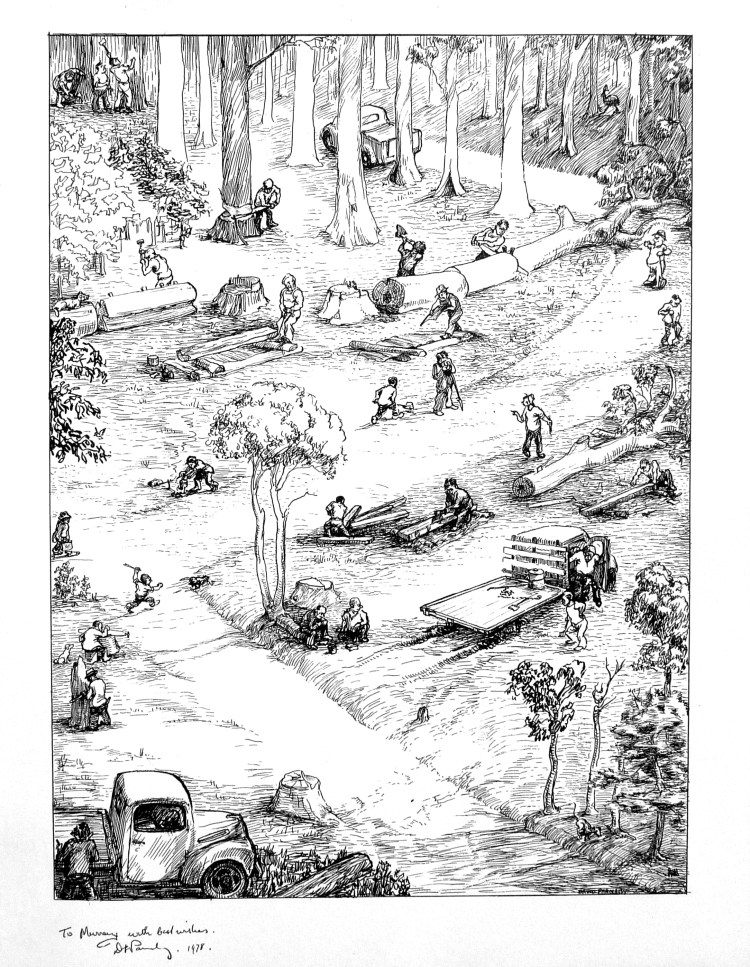

Providing timber for housing and domestic use from the State’s native forests, together with expanding softwood plantations, to support Victoria’s rapidly expanding population had always been an important goal for the Forests Commission.

It had also been a very a clear directive from the State Government to meet Victoria’s timber needs and to expand the State’s rural prosperity.

While there was a local sawmilling industry from the 1850s, Victoria relied heavily on imported timber until about 1900.

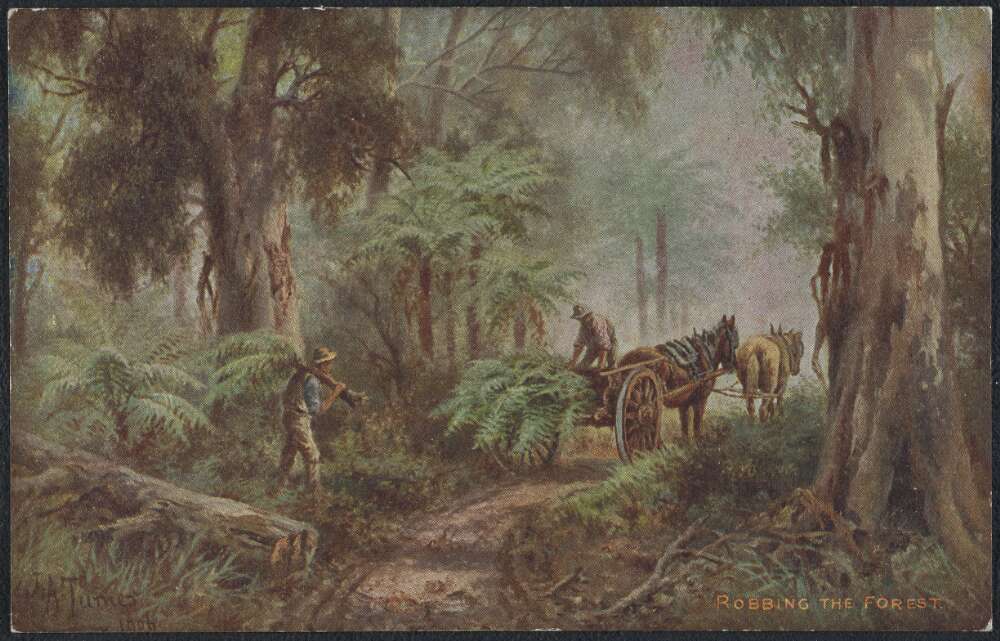

There was also an imperative to restore some of the damage done to the State’s forests caused by the indiscriminate cutting during the gold rush, and the mad scramble for land settlement that followed in the late 1800s.

There were loud calls, particularly after shortages experienced during WW1, to increase timber production from the State’s native forests to reduce the dependence on imports.

The timber supply shock was no doubt a factor in the State Government creating the Forests Commission as an independent entity immediately after the war in 1918.

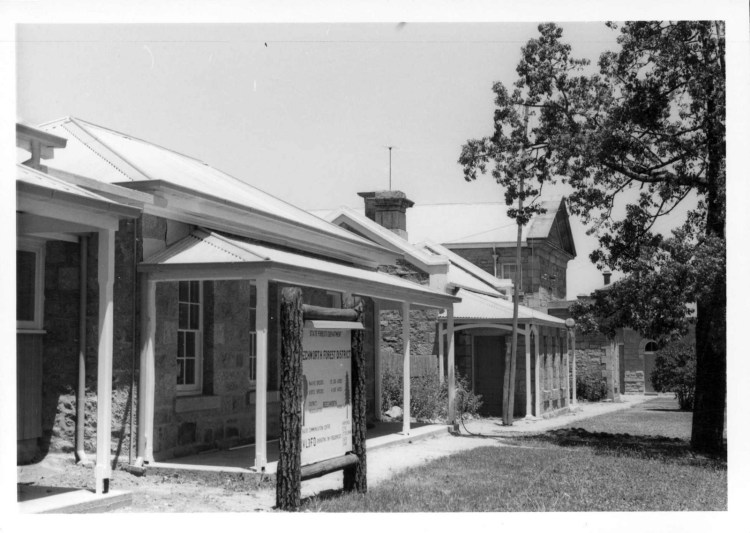

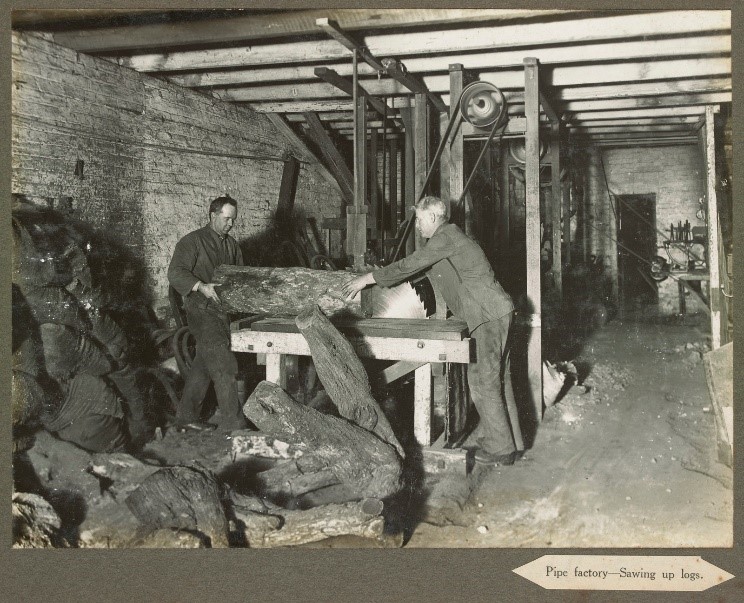

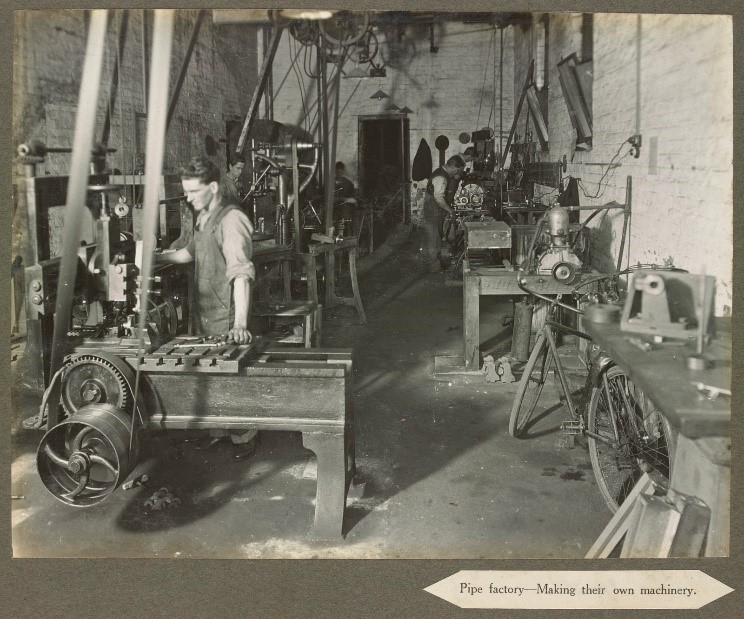

Experimental seasoning workshops and kilns had been established by the Department in 1911 to investigate the properties of local hardwood timbers and to develop a sawmilling industry.

The State Seasoning Works at Newport demonstrated the potential uses of Victorian hardwoods and this pioneering work done in partnership with the CSIRO bore fruit. By 1931 it was estimated that 80% of the flooring laid down in Melbourne was kiln-dried mountain ash cut from the State’s forests.

The research work at Newport and by Dr Herbert Eric Dadswell and his colleagues at the CSIRO from 1929 until 1964 the expanded the understanding and uses of native timbers.

Experimental softwood plantations had been established at Frankston and Harcourt in 1909. The largest plot was some 2,500 acres at the McLeod Prison farm on French Island in 1917, but the major softwood expansion wasn’t until the early 1960s.

Victoria’s native forests continued to provide sawn timber, heavy construction timbers, railway sleepers, power and telephone poles, fencing materials, firewood and pulpwood for papermaking.

Timber for Homes.

The rate of house construction between 1920 and 1939 was relatively steady, except for the period of the Great Depression in the 1930s.

Green scantling timber was used for wall and roof framing and sub-flooring. Dried and dressed hardwoods, particularly messmate and mountain ash, were used for internal flooring, door and window frames and architraves.

Softwood weatherboards were imported from Baltic States for external cladding, while old-growth Oregon was imported from North America for large structural timbers. Asbestos cement sheet was also used widely.

With the outbreak of WW2, the Commission’s efforts were directed towards salvaging the mountain forests burnt across the Central Highlands in 1939 and supporting the war effort.

Sawn timber production for domestic housing increased rapidly in the five years after the war, and then more than doubled by 1955, in the post-war housing boom.

From the mid-1950s the volume of sawn timber remained relatively stable, even though the number of new houses constructed each year increased steadily by an average of about 900 per year, from 20,700 in 1956, to 38,100 in 1976.

The increasing demand for housing during this period was coupled with a trend towards larger homes.

But while local green hardwood timber remained the main material for wall and roof framing, concrete sub-flooring and brick-veneer exterior cladding became increasingly popular which reduced the demand on native forests.

By the mid-1960s, sawmilling was recognised as one of Victoria’s largest rural industries which provided wide opportunities for decentralised employment.

Techniques for cutting and seasoning eucalypt timbers were well established while builders, architects and homeowners had come to appreciate the strength, versatility and beauty of Australian wood.

The Victorian Timber Promotion Council (TPC) was created by an amendment to the Forests Act in 1969. The TPC was supported by the Commission and sawmilling industry with a levy on all sawlogs. It strongly promoted the uses of local hardwood and softwood timbers and produced the popular Timber Framing and Stress Grading Manuals to support builders and architects.

There was a trend in the 1970s for particleboard flooring with carpet or cork covering instead of kiln-dried local hardwoods.

Victoria’s softwood plantation estate (both private and Government) also expanded during this time, but local softwood timber supplies remained very limited until the late 1970s when harvesting from the significant areas of maturing plantations increased.

In the decade from 1974 to 1983, it is estimated an average of 39,500 houses per year were constructed using timber from Victoria’s State forests.

And while average house size was continued to increase the use of timber per unit of floor space decreased steadily over that period. For example, the average house size in Victoria in 1974 was 150 m2, but then increased to 170 m2 by 1983. Over the same period the volume of timber per square metre of floor space decreased from an average of 0.14 m3 in 1974, to 0.11 m3 in 1983.

Over the period that reliable figures were reported (1900 – 2022), the volume of sawlogs harvested from Victoria’s native forests was about 90 million cubic meters. Production spiked during the 1939 salvage and then peaked in the early 1950s but then steadily declined.

And from 1932 to 1992, which coincided with the separation of the Victorian Plantation Corporation (VPC), the production of softwoods from the state-owned plantations was a further 9.5 million cubic meters and was continuing to grow.

There is no doubt that the Forests Commission contributed significantly to Victoria’s economic prosperity for more than six decades by ensuring there was a renewable and sustainable supply of timber from the States native forests and softwood plantations to build millions of family homes across Melbourne and regional Victoria.

Source: David Williams. Hardwood Timber for Victoria’s Houses. https://www.victoriasforestryheritage.org.au/activities1/producing/681-hardwood-production-and-houses.html

Galbraith (1943). Timber Resources of Victoria and Their Relation to Housing https://drive.google.com/file/d/1FPjht6smoS8vxfGzcrupTQdQ9kdU9cTr/view