Philip King was born in the remote Glen Valley in far eastern Victoria on the 12 Feb 1933 where he attended the local primary school. It was cold in the mountains where it often snowed, and the Omeo Highway was regularly blocked during winter.

Phil later attended high school at Richmond in Melbourne but soon returned to find a job closer to home in the office of the Glen Wills gold mining company. But the company finally closed in about 1950.

Gold had been discovered in 1861 in Wombat Creek, which flows northeast from Mount Wills. A couple of decades later, tin and silver were also found. Large amounts of money were invested in tin mines, but the results were disappointing.

Sunnyside was established in 1891 and grew by 1893 to have a population of about 300. The bustling townships of Glen Valley and Glen Wills also served the mines with post offices, schools and hotels. A public hall was built in 1936.

But like most small gold mining settlements, prosperity of the valley steadily declined as the gold petered out and all that now remains are a few houses and farms.

The Grand Design.

The devastation of the 1939 Black Friday bushfires was unprecedented. Several townships were entirely obliterated leaving 71 people dead including four Forests Commission staff, 69 sawmills were lost and over 3700 buildings were destroyed.

Nearly two million hectares of Victoria’s State forests were burned. The intense bushfire killed vast swathes of mountain ash, alpine ash and shining gum in the Central Highlands, some for the second time since earlier bushfires in 1926 and 1932.

In the wake of the catastrophic bushfires and the scathing Stretton Royal Commission report, a quiet revolution began across Victoria’s state forests. An epic story that took decades to unfold and where several things were in play.

- Salvage of the fire-killed trees became an urgent and overriding task for the Forests Commission. It was estimated that over 6 million cubic metres needed to be harvested, and quickly, before the dead trees split and the valuable timber deteriorated.

- Severe shortages of labour and other pressing needs during the war years slowed the task but the massive timber salvage program was virtually completed by 1950.

- The mountain ash forests in the Central Highlands were regenerating vigorously after the bushfires but they wouldn’t be available for timber harvesting for many decades to allow them enough time to regrow.

- It was apparent that Victoria’s timber industry needed to shift to the east and northeast but it was always intended that it would move back into the Central Highlands once the ash resource had recovered in about 60 to 80 years’ time.

- Meanwhile, the demand for hardwood timber for the post-war housing boom continued unabated.

- The Forests Commission was under considerable pressure to identify new timber resources to replace the mountain ash lost in the 1939 fires. The alpine ash stands to the north of Heyfield and the east of Mansfield came into particularly sharp focus.

- The Commission also needed to make its own maps of the remote forests using the aerial photographs taken by the RAAF during the war years.

- Based on new and more reliable assessment figures, decisions could be confidently made about the allocation of timber licences and the location of new sawmills.

- The memory of the losses of in the 1939 bushfires was still fresh. And despite strong and vocal opposition, the Forests Commission refused to allow new sawmills to be rebuilt inside the forest as they had before 1939. But those few that still existed were permitted to remain… for a while anyway.

- The advent of more powerful bulldozers, crawler tractors, geared haulage trucks and petrol chainsaws dramatically changed logging practices.

- Diesel and roads were rapidly replacing steam and rails.

- The newly built and expanded departmental road and track network made it feasible for trucks to haul logs directly from the forest to town-based sawmills within a few hours.

- The earlier research done at the Commission’s Newport seasoning kilns was bearing fruit and Victorian eucalypts became highly prized for flooring, joinery and furniture and the timber industry began investing in new value-adding equipment.

- Victoria’s softwood industry was relatively modest at the time until planting expanded in 1961.

- An agreement was negotiated between the Forests Commission and Australian Paper Manufactures (APM) in December 1936 and the mill began taking pulpwood at Maryvale to make heavy-duty Kraft paper from October 1939. This had a big impact on the utilisation of lower quality logs and the economics of the logging industry.

The main social and economic beneficiaries of the Grand Design and the big move east of the Victorian timber industry were small rural settlements like Heyfield, Mansfield, Myrtleford, Bruthen, Nowa Nowa, Orbost, Cann River, Colac, Alexandra and Swifts Creek, which grew into thriving communities based upon State forests.

These places became flourishing “Timber Towns” with jobs, decent housing, schools, shops, sporting clubs, public transport and health care. A more secure and safer place for families than the itinerant sawmills set deep in the bush which was characteristic of the earlier period.

The visionary architects behind the Grand Design were the Chairman of the Forests Commission, A.V. Galbraith, together with the Chief Fire Officer, Alf Lawrence, who was appointed after the 1939 bushfires and later became FCV Chairman until he retired in 1969. Undoubtedly, Sir Albert Lind, the Minister for Forests and local MP for East Gippsland from 1920 to 1961, played an influential role too.

The Forest Assessors.

The Victorian State Government invested heavily. The stakes were high, and it was critical for the Forests Commission to collect accurate timber volume figures because future decisions about new sawmill locations were to have long-term social and economic ramifications.

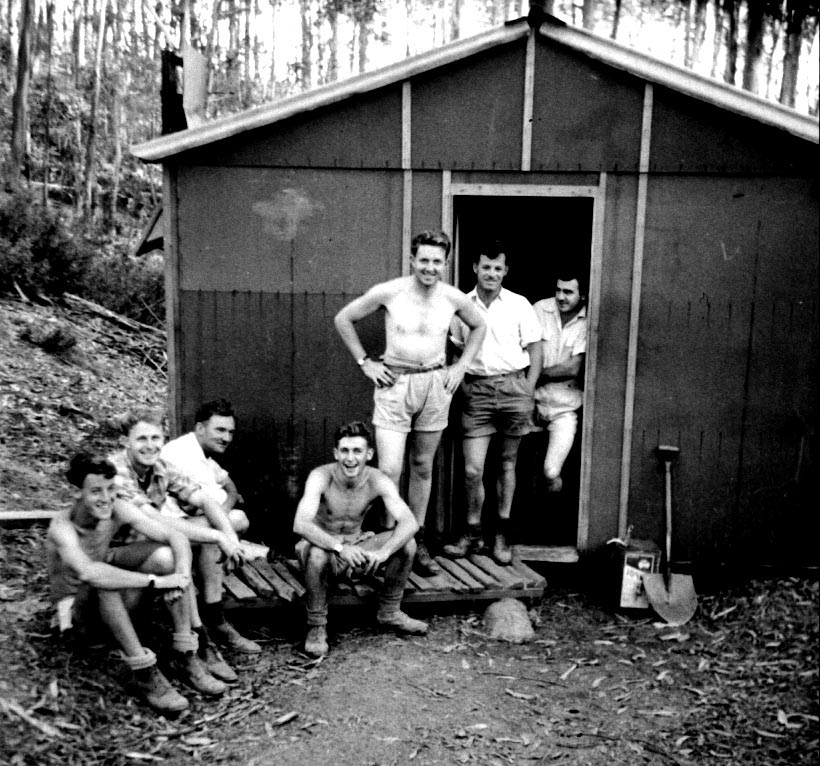

Forest assessment crews were nomadic and established rudimentary base camps deep in the bush. They were also resourceful and lived under canvas, in cattlemen’s huts or sometimes took a couple of portable and prefabricated flat-pack Stanley Huts with them.

They could be away in the mountains for many weeks at a time with little contact with the outside world other than a scratchy RC-16B radio.

They were fit and lean and life was Spartan. Fresh food and supplies travelled on rough 4WD tracks or by packhorse, so crews often supplemented their meagre rations by living off the land.

Rough and steep terrain, sketchy maps, occasionally getting lost, toppling off horses, thick scrub, snakes and wire grass lurking with a myriad of other bighty and prickly things. The vagaries of the weather like heat, snow, dangerous river crossings, falling trees and the ever-present threat of bushfires. There were occasional injuries.

If assessors needed to trek away from their basecamp for a few days, they took the minimum amount of stuff and slept under the stars.

While it all sounds very romantic, it was harsh and lonely and by the end of a long summer bashing through the scrub each day the novelty had worn off and tempers sometimes frayed.

There was also a challenge of crew leadership to be rapidly learned on-the-job. And for many first-year forestry school graduates being posted to Assessment Branch for a couple of years was a rite of passage and a solid grounding.

Leon Pederick graduated from the Victorian School of Forestry at Creswick in December 1950 and like so many others before him was posted to the Assessment Branch. After some initial assessment jobs and more training at the Kinglake Assessment school, Leon led the Glen Wills team to measure trees in State forests near Mt Bogong in October 1952.

Meanwhile, Phil King was only 19 when he returned from a short stint in compulsory National Service with the Army. He was driving a cow home to Glen Valley and happened to be walking past an old timber cottage at Sunnyside which was owned by the Forests Commission and where Leon’s forest assessors were setting up camp. He was approached by Ray Brash about a job as chainman in the assessment crew which he readily accepted.

And so began a lifelong career with the Forests Commission.

Phil’s task was simply to bash through the scrub on a set compass bearing pulling a metal measuring chain while at the same time pushing down the wiregrass and kicking the tiger snakes out of the way. The assessors would follow in his path and measure the trees one chain on each side of the narrow strip. Being chainman was difficult and arduous and not many people had the stamina or fortitude to last long in the job.

Their initial surveying of roads, tracks and ridges through the alpine ash forest near Glen Wills was not difficult, but the work became more strenuous when they had to leave the tracks and follow fixed bearings through the steep countryside.

And for the assessors, having a good sense of direction, being able to read a paper map and use a measuring chain, prismatic compass and dead reckoning were essential skills, as well as a stout pair of walking boots to somehow navigate through the bush and get back to camp at the end of a long day.

But getting lost was embarrassingly common, particularly in broken or undulating terrain with few roads or tracks. And in the days before GPS, walking up to a hilltop or ridgeline to get a better view and reset your bearings was often the most practical solution.

The team were in radio contact with the Commission’s Tallangatta office. Orders for food and supplies were relayed to shops and then transported on the bus which serviced Glen Wills each day.

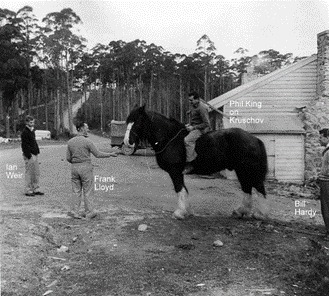

Because Phil showed good horsemanship skills, he was soon elevated to the important job as packman to move supplies and equipment as well as setting up temporary camps at old cattleman’s huts and in the bush for the team.

There was frequent vehicle trouble, with the Land Rover and Dodge truck out of action at regular intervals. Sometimes they were able to take them to Tallangatta for repairs, but other times the crew did their own maintenance and somehow kept them running.

At the conclusion of the Glen Wills assessment, the team moved to Bullengarook near Daylesford and lived in the old internment camp at Bullarto used during World War Two. They had been sent to measure pole-sized mixed species forests that had regenerated after the damage done to the bush in the decades following the Gold Rush of 1851.

It was while at Bullarto that a couple of the crew members pooled their cash to purchase an old 1927 Packard sedan from a Malvern car yard to get around on the weekends. It served the team well providing transport to frivolities in Melbourne every second weekend, costing one penny per mile to cover fuel and running costs.

There were several more assessment projects before Phil transferred to a less transient position based at Tallangatta to build new roads and 4WD tracks working for Kevin O’Kane.

But the lure and adventure of assessment remained, and Phil returned for several more tours at Benambra, Tom Groggin, Heyfield and the Otways.

In 1956, the Forests Commission underwent a major internal restructure by amalgamating the hardwood and plantation divisions to create 56 new forest districts, each under the control of an experienced District Forester. Things remained largely unchanged for the next three decades. In about 1960, Phil secured a role based at Omeo in the newly formed Swifts Creek District working for Moray Douglas.

Forest Forman’s School – 1962.

In 1962, while working at Omeo, Phil was fortunate enough to be selected for the coveted Forest Forman’s school based at the No. 1 Camp in the Mt. Disappointment State forest. Foresters, Max Boucher and Fred Craig, were the main lecturers during the intensive nine-month course.

The camp had previously been used to house Italian internees and later German POWs during the war and was remote from any townships and cold in winter.

But the course changed Phil’s life and he kept in contact with his 1962 cohort of classmates and their families over the subsequent decades.

Forest District Life.

Upon graduation, Phil had short postings with the Forests Commission, firstly at Daylesford for two months, then Orbost for another two months, before finally settling at Broadford in May-1963. He was appointed as a probationary Forest Foreman and, from June 1965, as a permanent Forest Overseer, a job he enjoyed for the next 14 years.

Forest foreman and overseers were the backbone of the Forests Commission and became undisputed kings of their domain with overall operational control of their individual patch of bush. In addition to firefighting, road maintenance and other works, one of Phil’s main tasks was marking trees to be felled in the bush before they were snigged out and loaded onto trucks to go to local sawmills.

Unlike Creswick foresters who were regularly and compulsorily moved around the state by the Forests Commission every few years, Forest Overseers tended to stay in the one place for longer periods and so got to know the bush and their local communities.

But in 1977, Philip King (one L) decided to move back to East Gippsland as a forest overseer based at Nowa Nowa and took supervision responsibilities for all the post and sleeper cutters in the coastal and foothill forest as far as the Lakes-Colquhoun Road. His long-time nemesis Phillip Morgan (two Ls) operated on the other side from Mt Taylor near Bruthen.

And like all forest overseers, Phil had an active role in bushfires and fuel reduction burns but in later years became noted across East Gippsland for his exemplary skills as a catering officer and camp cook. A very important role at any bushfire.

The Forests Commission surrendered its discrete identity in 1983 when it merged into the newly formed Department of Conservation, Forests and Lands (CFL).

It took some years for the new regional structure to settle, but Phil remained at Nowa Nowa largely unaffected by the turbulence going on around him.

However, the tempo of change accelerated after the initial amalgamation in 1983 with many more departmental restructures and name changes occurring over the subsequent decades.

Widely known and well regarded, Phil retired in 1993 after 41 years of service from what by then had become the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (CNR).

And like most forestry employees, Phil was always encouraged to be active in his local community. He had joined the Lions Club of Australia and was later elevated to the senior leadership position of the District Governor.

Phil recently turned 90 and is still fighting fit with a sharp memory and is full of rich stories of his time in the Forests Commission.

Main Photo: Retirement – Sam Bruton, Doug Stevenson (CNR Regional Manager), Phil King, Ray Bennett, Norm Cox – 1993.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1-I-W4LmdJekuTHpjmEiwN_2M-kFPbpkL/view

The assessors.

https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/4CD4F787-FD8E-11EA-BE8C-612FB3FF00FD/content

MIDDLE: David Paterson, Frank Gerraty, Phil King,

FRONT: Ray Brash, Gordon Doran.

Leon Pederick, David Anderson, Eric Bachelard, Bill Clifford.

L / R; Bert Allen, Jack Hutchison, Don Dyke, Geoff Mair, Col English, Ron Smedley, D’Arcy Smith, Ron Harris, Stan Kirkham, Bill Barnes, Des Kelly, Jack Blythman, Clarrie Pring, Len Arnold, Ken Doyle, Tom Waldron and Max Seamer. FCRPA Collection

Peter,

Thanks, a good story.

I see the reference to:

Nearly two million hectares of Victoria’s State forests were burned. The intense bushfire killed vast swathes of mountain ash, alpine ash and shining gum in the Central Highlands, some for the second time since earlier bushfires in 1926 and 1932.

Is there any info that relates to the loss of area of these species due to the repeated bushfires in 1926, 32 and 1939? Or mapping overlays of the three bushfires against current ash to consider possibilities of loss. Or interviews/ reports at the time of the bushfires.

John

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi there. There are no maps of 1926 or 1932 but the Stetton Royal Commission has a good map for 1939. The multiple fires led to large areas that had no eucalypts. This was different from the Strzeleckis and Otways which had been cleared for farming and abandoned. The Commission had several reforestation programs over the years. https://www.victoriasforestryheritage.org.au/activities1/reforesting-regenerating/160-toorongo-reforestation.html

LikeLike

Good morning Peter, What an interesting 🖼 about Phil King. I haven’t seen him for awhile, probably because I don’t spend a lot of time in the shops and I’m away a lot. Moray and I had a lot to do with him when we were at Swifts Creek in the 1960s and then again when we moved to Bairnsdale. Phil was very good to one of our sons who was with the fire crew. He boarded with Phil in Nowa Nowa. Ray Brash was my brother in law. Those assessment lads were a fairly tight-knit group! Hope you are well and have escaped Covid ! Best regards, Rosemary

Rosemary Douglas, Box 1400. Bairnsdale 3875

rosmoray@netspace.net.au

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. I sat down with Phil a while ago to write his story. He is 90 but still pretty sharp. Have mostly avoided Covid. Cheers

LikeLike

great story of life in the early forestry era. Really explains how things actually worked in the bush. From an old Orbost bloke, enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person