As the summer bushfire season of 1943-44 opened, Australia had already endured four years of war with many men and women away overseas or deployed to northern Australia.

In Melbourne’s bayside suburbs, as in all parts of Australia, austerity measures were in place with rationing of food, petrol, clothing, gas, electricity, firewood and other basic goods. There were also severe labour shortages which affected essential services like the railways, as well as community organisations such as the Red Cross and volunteer firefighters.

Melbourne was hot in January, and the driest since colonial records began. Less than three quarters of an inch of rain fell, less than a third of the long-term average, as drought conditions gripped much of southern Australia leaving many areas tinder dry and fire prone.

The early weeks of 1944 produced heat waves with temperatures exceeding 100 degrees on the old Fahrenheit scale.

Bushfires just before Christmas on 22 December 1943 had already killed 10 firefighters near Wangaratta.

Eighty years ago today, on Friday 14 January 1944 bushfires raged at Daylesford, Woodend, Gisborne and other central Victorian towns near Bendigo. To the west of Melbourne there were blazes out of control from Geelong to the South Australian border. Fires burned near towns such as Hamilton, Skipton, Dunkeld, Birregurra, Goroke and Geelong itself.

Friday was hot with a strong dry northerly wind, the maximum temperature rose to 103.2° F with a maximum wind gusting to 54 mph, the relative humidity fell to 6% and the moisture content in fuel plummeted to about 2%.

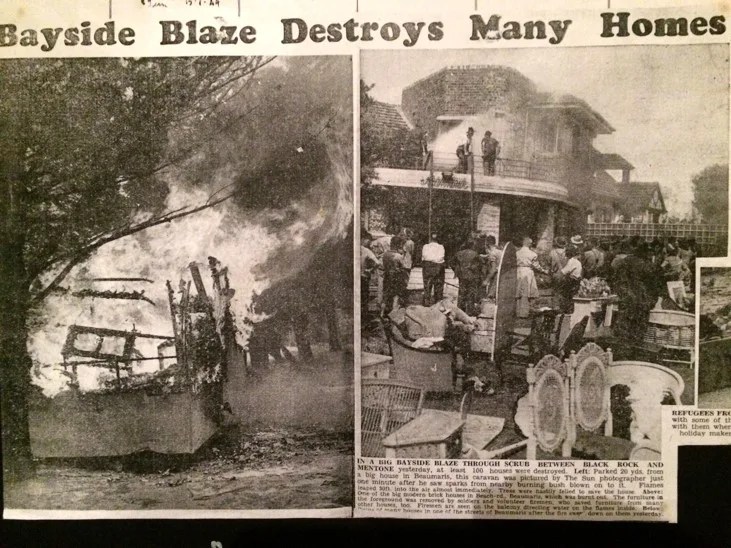

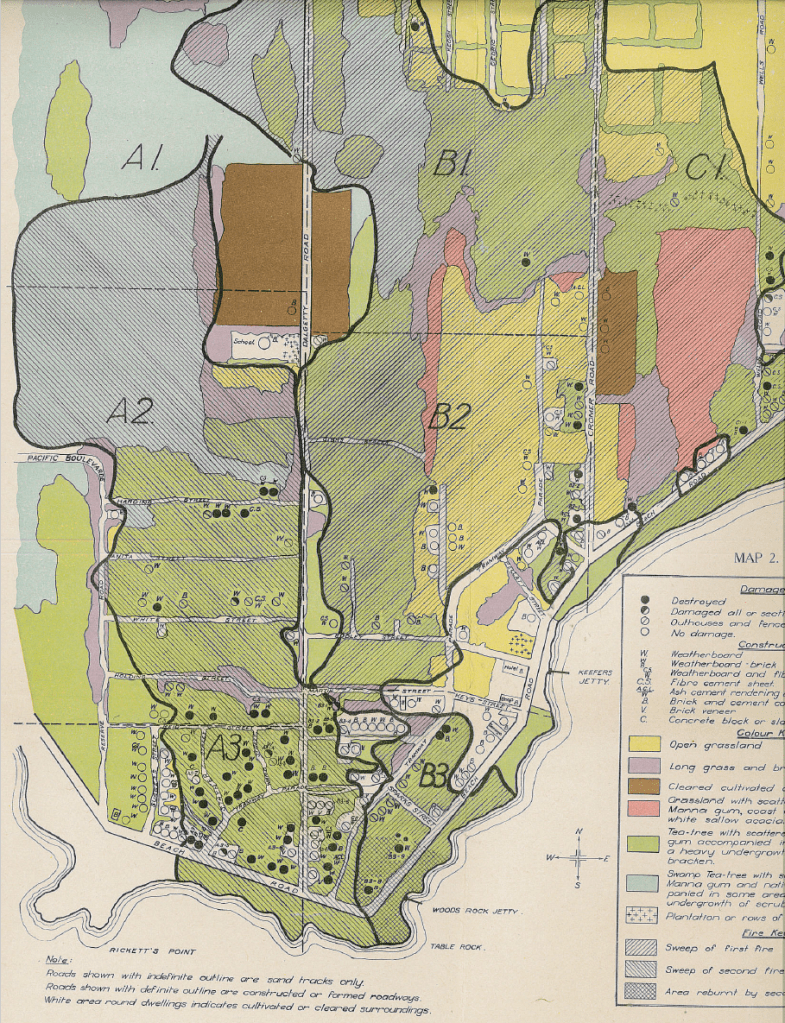

In the sleepy beachside suburbs of Beaumaris, Cheltenham, Black Rock and Mentone, about 12 miles south of Melbourne, the threat came swiftly as two overlapping bushfires broke out during late morning. The first began near the corner of Bay Road and Reserve Road and spread into the grounds of the Victorian Golf Club. It was followed by another nearby blaze soon after.

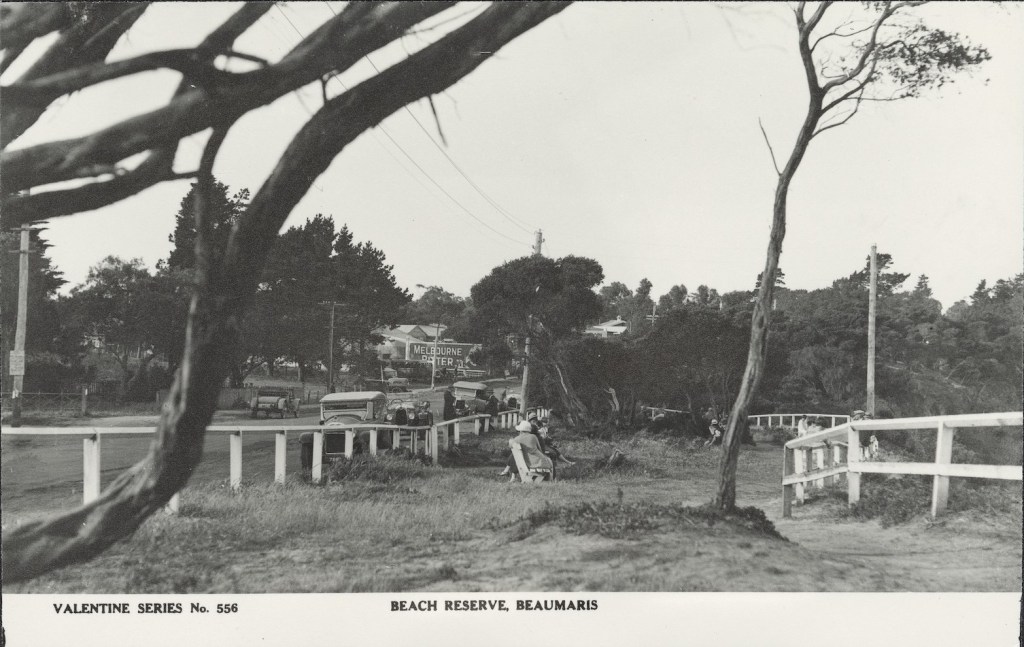

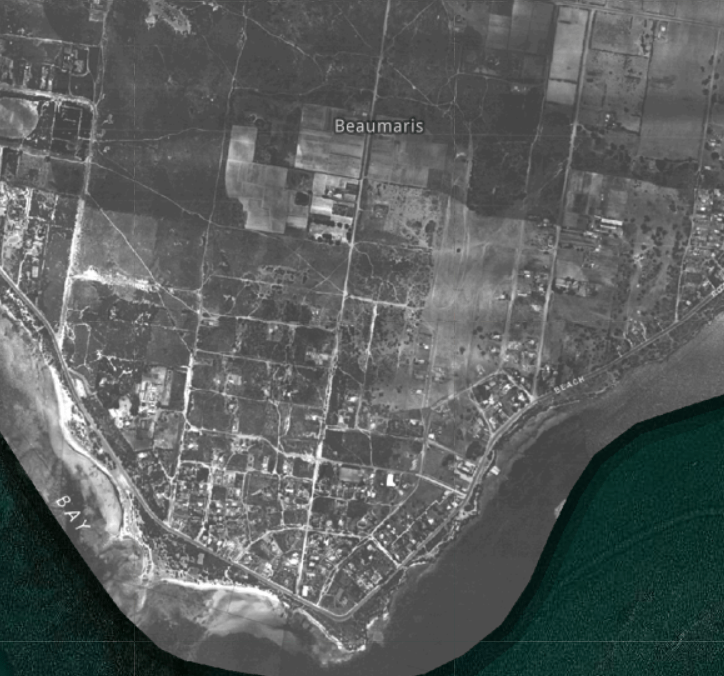

At the time, these neighbourhoods resembled small coastal villages with unmade roads, sandy tracks and modest weatherboard and fibro-cement houses scattered throughout the dense thickets of t-tree scrub with overhanging manna gums and an understory of acacias and tall bracken. There was also a string of more substantial brick homes with manicured gardens along Beach Road overlooking Port Phillip Bay.

The inferno headed south and burned properties along Beach Road towards the Beaumaris Hotel and eventually reached the foreshore near Table Rock.

Fire brigade officers reported that the water pressure was so poor that their hoses were useless, the flow being little more than a trickle even when pumps were used.

The fire also cut telephone and electricity as the timber poles burned and fell blocking many streets.

The fire occurred before the formation of the Country Fire Authority (CFA) and there was limited coordination and communications amongst volunteer firefighters. Control was quickly handed over to the Melbourne Metropolitan Brigade’s (MFB) Chief Fire Officer, James Kemp, when the extent of the disaster became obvious.

Large numbers of volunteers, air raid wardens, army personnel from barracks at Caulfield, State Electricity Commission (SEC) staff, police, residents and regular firemen fought the blaze.

Some residents evacuated to the relative safety of the beach. It’s reported that some put what possessions they had managed to grab into small boats to keep them safe. But one boat loaded with suitcases broke loose and drifted out to sea, driven by the strong northerly wind and was eventually recovered the next day near Williamstown.

The fire eventually burned itself out late on Friday afternoon when it reached scrubland on the coast near Rickett’s Point.

The overall fire area was comparatively small at about 1500 acres, and the part burnt by flames only totalled 700 acres. But the ferocity of the blaze placed some 118 houses in grave danger and 58 homes were destroyed, with 8 others suffering serious damaged. An additional 57 properties sustained damage to outside sheds, dunnys and fences.

Most of the losses were behind the iconic Beaumaris Hotel in the Tramway Parade area. Another eight homes were lost along Dalgetty Road. Cromer Road, Coreen Avenue, Hardinge, Rennison and Stayner Streets. The caravan park on Beach Road was also burned with the loss of seven vans and five motor cars.

Thankfully no lives were lost, but 20 were killed in other parts of Victoria.

The Prime Minister, John Curtin, announced an immediate £200,000 Commonwealth grant for fire victims in NSW and Victoria, while the Victorian Premier, Albert Dunstan, added a State grant of £50,000. Public appeals were also opened which were co-ordinated by bayside councils.

As is always the way, the aftermath of the Beaumaris fires produced a flurry of finger-pointing and attempts to shift blame.

Issues arose over road construction, power and water supplies as well as restrictions on clearing of native vegetation. The risks of charcoal gas producers on cars and uncontrolled burning off by residents also received notable mentions.

Because of wartime austerity measures and shortages of building materials, it took years for communities to rebuild. Many families simply moved away, and it wasn’t until the 1950s and Melbourne’s post-war housing boom that the suburbs rebounded.

There was also justifiable public outcry at the lack of government action after similar events five years earlier in 1939 and the landmark Royal Commission by Judge Stretton. One of his key recommendations had been to create a single fire service for country Victoria.

These fires, along with those at Wangaratta and Yallourn a month later on 14 February 1944 finally forced the State Government to act. The Premier Sir Albert Dunstan and Minister for Forests Sir Albert Lind, who had both delayed legislative changes in Parliament, decided there was no alternative but to ask Judge Stretton to chair a second Royal Commission.

Stretton’s report returned to his earlier themes and once again highlighted the lack of a cohesive firefighting ability outside the Melbourne area.

After nearly six months of debate and argy-bargy in State Parliament, legislation to establish the Country Fire Authority (CFA) was finally passed in two stages on 22 November and 6 December 1944. The Chairman and Board members were appointed on 19 December 1944. The CFA came into legal effect on 2 April 1945.

https://localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au/articles/319

Excellent write up

LikeLiked by 1 person