On St Valentines Day, 14 February 1926, the bushfires already burning in the State’s forests joined up, fanned by gusty winds up to 60 miles per hour. Places like Warburton, Powelltown, Gilderoy, Gembrook, Noojee and Erica bore the brunt of the inferno in what later became known as Black Sunday.

An accurate and consistent tally of those killed remains elusive. Assessments vary between 30 and 60, but the official figure given by the state government’s relief fund in November 1926 put the toll at 30, although 31 is also commonly quoted.

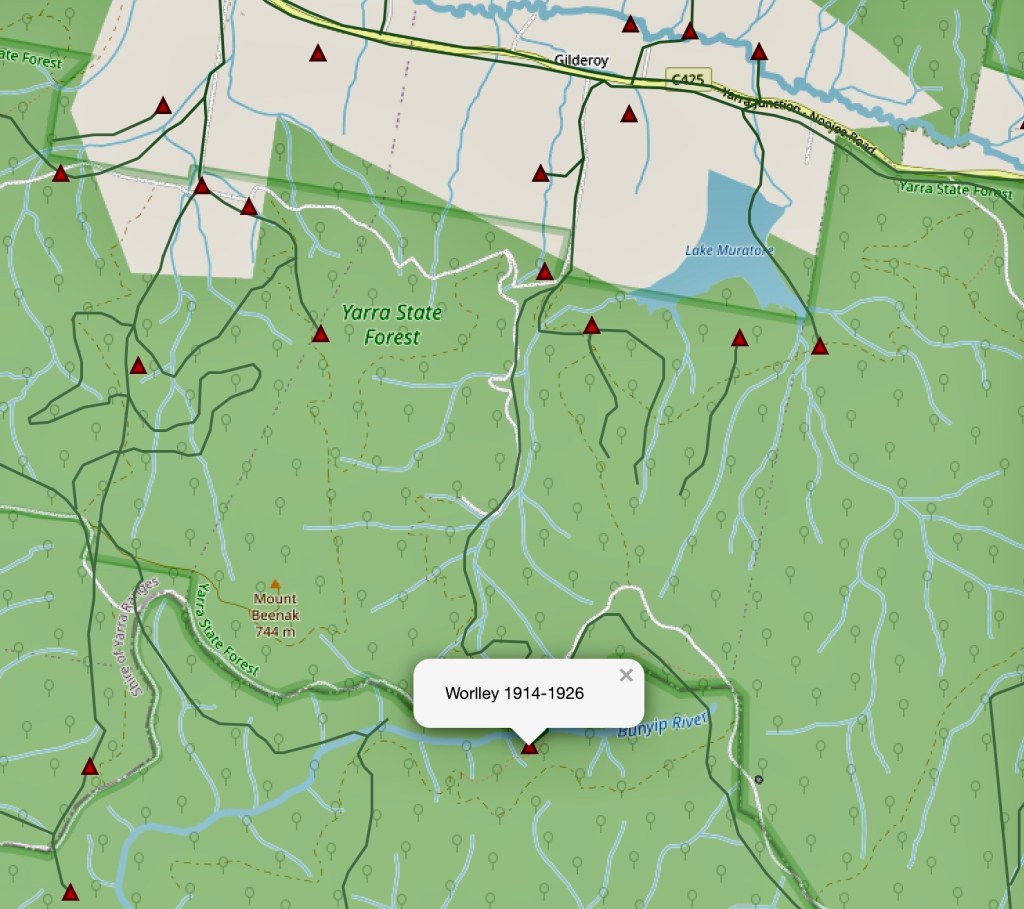

The greatest single tragedy occurred at Worlley’s Mill, deep in the headwaters of the Bunyip catchment, about two miles south of Gilderoy.

The mill had grown into a sizable settlement with a boarding house and storeroom, seven cottages, twelve small huts and horse stables.

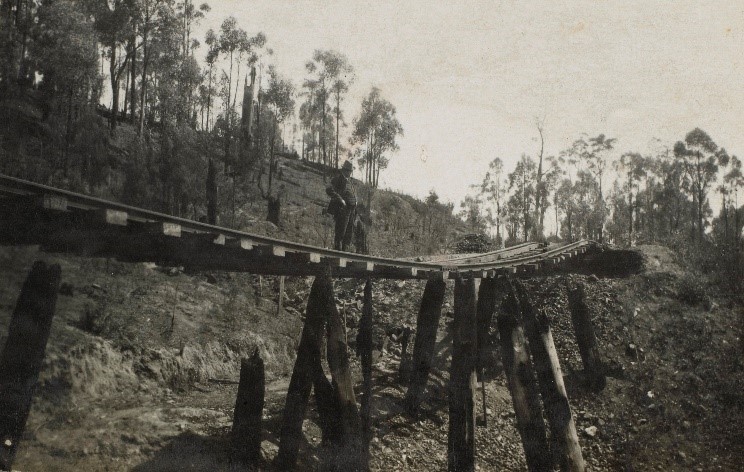

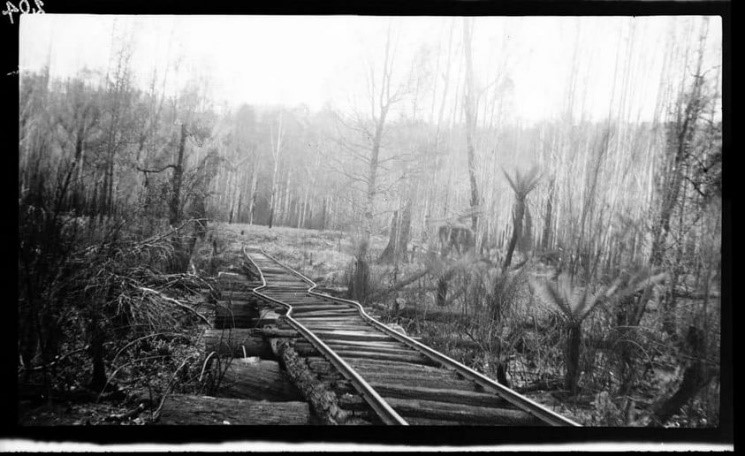

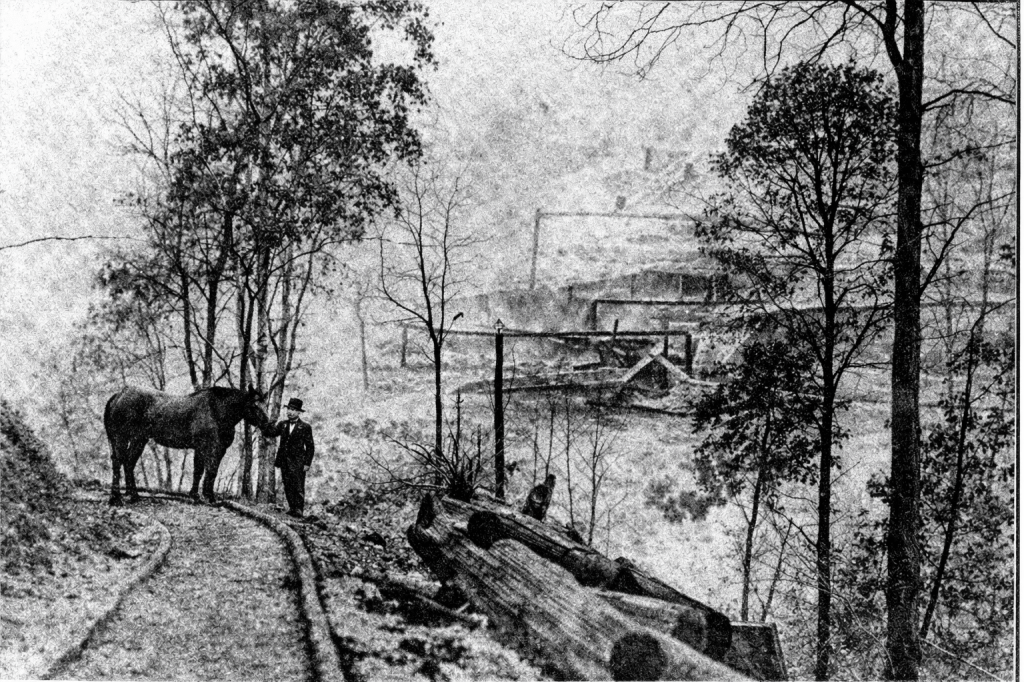

The only access was along a steep and narrow timber tramline running through the bush along Saxton Creek in the Little Yarra Valley

Sunday morning dawned hot with a rising northerly wind and by midday the smell of smoke was strong, with scorched leaves falling around the mill.

The sawmill residents were unaware that a major fire, driven by the strong winds, was moving up Mount Beenak, while another fire advanced along McCrae Creek near Gembrook to the west. The two fires then merged and swept along the ridge towards them at about 2 pm.

A desperate fight was made to save the mill and settlement, but it soon became apparent that it was hopeless. They split into separate groups.

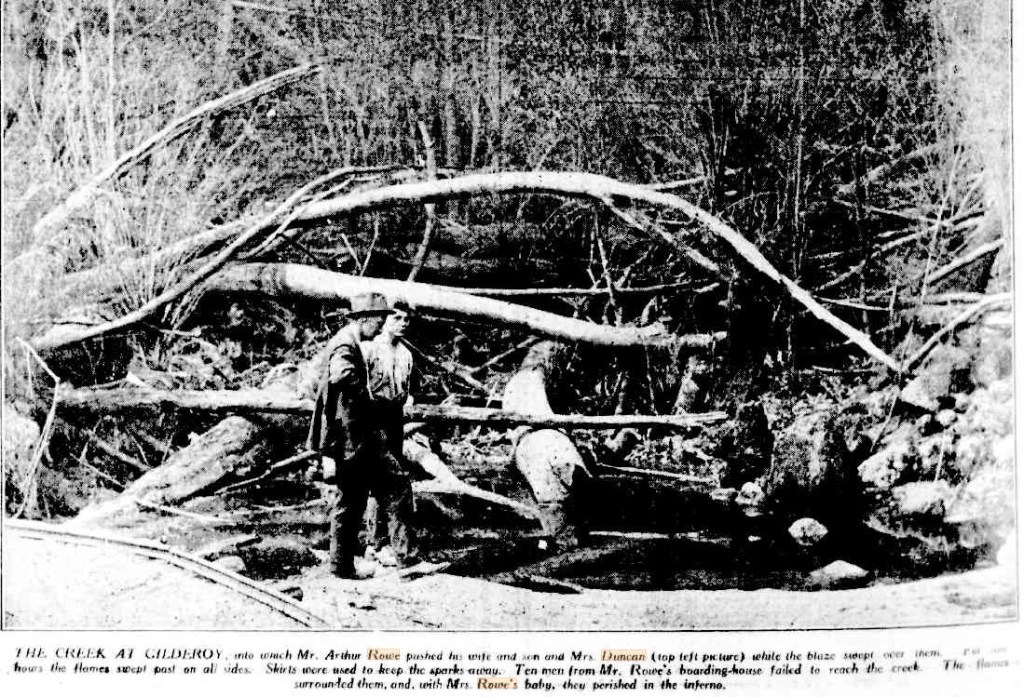

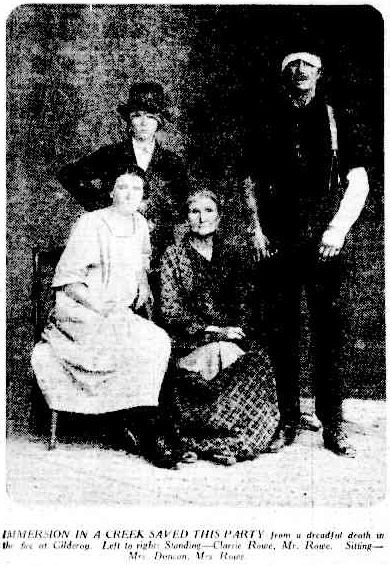

Together with Mrs Elizabeth Duncan, who had only been at the mill for about a week and was helping Mrs Rowe to run the boarding house, the group of four then managed to make their way to a small creek containing about a foot or two of water. Mr Rowe made them lie down and began splashing them with water.

Even though they sheltered in the shallow creek until dusk they were still badly burned, and Mr Rowe was temporarily blinded.

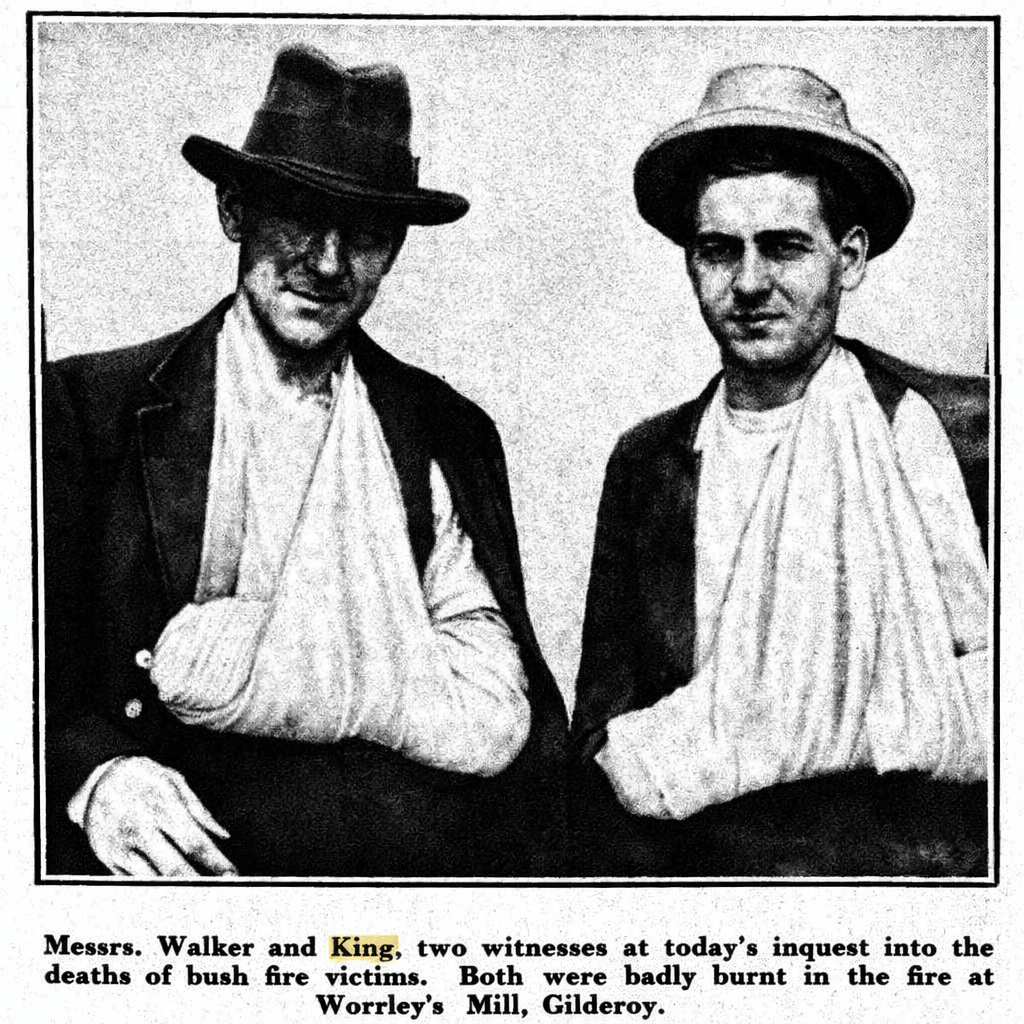

The fire at the mill was closing on three sides and in desperation, Harry King and Arthur (Joe) Walker used their coats to shield their faces and dashed through the fire front. Badly burned and with their hair and eyebrows singed, they managed to reach the same small creek about five or six chains away where they lay for about three hours.

The other group of mill workers and their families, led by Lindsay King, attempted to escape to Beards Farm back along the wooden tramway towards Gilderoy, but their path was soon blocked by fallen trees and cut-off by flames, so they were forced to retreat. But they had nowhere to go and eleven bodies were later found within a radius of just 20 feet.

In the confusion, Mrs Duncan had become separated from her son, Richard, aged two years and seven months, who had been taken by Lindsay King leading the party trying to escape back on the tramway to Gilderoy. This was the last time she saw her son alive.

When the fire had finally passed, all six survivors were exhausted and slept for a few hours before making their way to the Saxton’s house at Gilderoy next morning to raise the alarm.

Fourteen people died that manic Sunday afternoon at Worlley’s Mill including one woman and three children. Most were later buried at Wesburn.

Ten other sawmills near Gilderoy were destroyed, along with numerous homes and many miles of timber tramway.

A dozen horses perished at Powelltown as the women and children sheltered on the bowling green with the sprinklers going. All the houses were destroyed but the mill itself was saved. Many more mills surrounding Powelltown in the bush were destroyed.

The small settlement at “The Bump” railway tunnel was razed.

Further east, Noojee, founded in 1902, had grown into a bustling railway terminal supporting outlying farms and bush sawmills with stores, a post office, hairdresser, hotel, motor garage, railway station, a hydroelectric station, and community hall. The school had opened in 1922 after much local agitation. But every building in the town, including 45 homes, apart from the Methodist Church, hotel and motor garage were destroyed in the bushfires. Parts of the vital connecting railway and bridges were also lost. Newspapers speculated that it was unlikely that the township of Noojee would ever be rebuilt.

It was estimated that another 30 mills in the Warburton and Erica districts were also destroyed.

A cool change arrived late on Sunday evening which brought a little rain.

John Schauble (2019). Victoria’s Forgotten 1926 bushfires, Victorian Historical Journal. Vol 90 (2), December 2019, pp 301-317. https://www.historyvictoria.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/VICTORIAN-HISTORICAL-JOURNAL-December-2019.pdf

Peter Evans. From Central Highlands RFA reports. Pers Comm.

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3735307/445964

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3739040

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/244055584

Argus, Wednesday, 17 February 1926. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3735162

The Sun news pictorial, 17 February 1926 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/31195356

The Sun news pictorial, Wednesday 17 February 1926 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/31195356