The Stretton Royal Commission into the 1939 bushfires considered in detail the use of bushfire dugouts. The report noted –

After the 1926 fires, the question of insisting upon the installation of dugouts at mills for protection of the millworkers was raised by the Forests Commission. The Commission was divided in opinion and the matter lapsed. Again, after the 1932 fires, the question was revived. In May 1932, an engineer’s report upon the desirability of dugouts and on their construction was submitted to the Commission. Further consideration was given the matter and, on the 14th November 1932, the following minute was placed on the file:—

“Commission Decision – All sawmillers to construct effective dugouts in the close vicinity of all sawmills, particulars of such to be forwarded to the Commission”.

The Judge harshly criticised the Commission when he noted:-

Having made its considered decision, the Commission at no time thereafter took any steps to compel the observance of the condition. Instead, for several years, it wrote to millers “strongly advising” and “urging” the dugouts be instituted. In many cases the advice was ignored, and no dugout was constructed. In no case was even a threat of coercion made against the recalcitrant miller.

Many of the sawmillers objected strongly at the Stretton hearings to the compulsory installation of dugouts because of the expense. They objected even more strongly to constructing dugouts at steam winch sites because of their temporary nature.

The Forests Commission explained at the Stretton hearings that it had believed in dugouts as safeguards; that, in the words of the Chairman, A. V. Galbraith, their “belief had been intense”; that it continued to believe in them; but that it had feared it might be liable if people were asphyxiated in them; that it had sought advice of the Crown Solicitor on this point and had been advised that it would not be liable; that it had continued to “urge” the millers to install dugouts; that its fear of causing asphyxiation had remained until the 1939 fires proved it to be groundless.

But well-constructed dugouts had saved the lives of many sawmill workers and their families during the 1939 bushfires. In some locations, they had proved fatal.

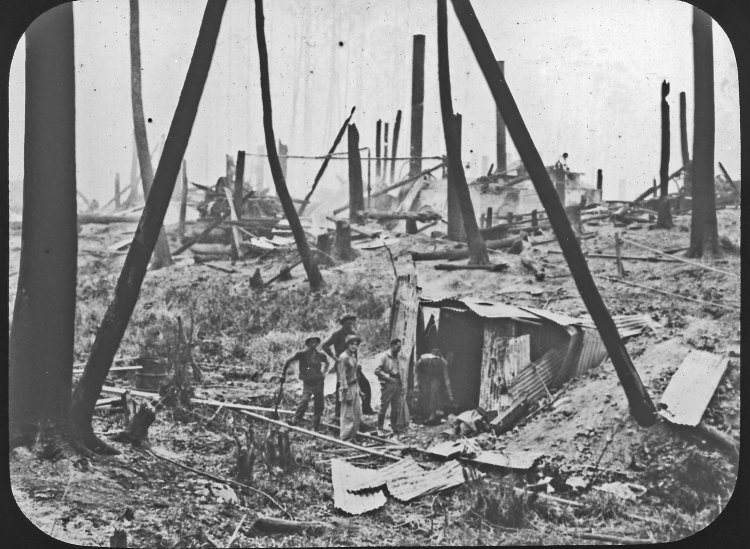

Ironically at Yelland’s mill near Matlock, 26 people were saved because they did not use the dugout, which was roughly constructed above ground of corrugated iron and which stood among standing timber. They instead sheltered in a brick house which was near another wooden building, which soon caught fire, as did a truck outside along with 24 drums of fuel and oil which exploded.

The brick building then also caught alight and the ceiling began to cave in, so the people inside climbed through a window and ran past the burning truck to an area missed by the fire. The sawmill chef, Mrs Vera Maynard, was caught by the flames and burned to death in the house.

Whereas at the nearby Fitzpatrick’s mill, 16 people burned to death because there was no dugout available. Scrub came right up to the borders of mill. Some men tried to find shelter behind the brickwork of the boiler house, but they were driven out by the flames. Others ran to the sawdust heap, thinking it would protect them from the searing heat, but their bodies were later found where they had tried to burrow into it.

The eight mill horses, still harnessed, were caught by the flames and died in their stalls.

One man jumped into an elevated water tank and is often said to have boiled. Other bodies were found in the bush about three-quarters of a mile away as they tried to run. Only George Sellars survived by wrapping himself in a wet blanket.

The two mills were not considered by their owners to be particularly vulnerable, and no worthwhile precautions had been undertaken for the safety of those who worked there.

It’s even reported that Forests Commission Officers, Finton Gerraty and Roly Parke, didn’t think the Matlock forests would burn as they did, and besides, there was a quarry nearby which offered some protection for the mill workers. They also had reservations about their legal power to insist on the owners’ building dugouts.

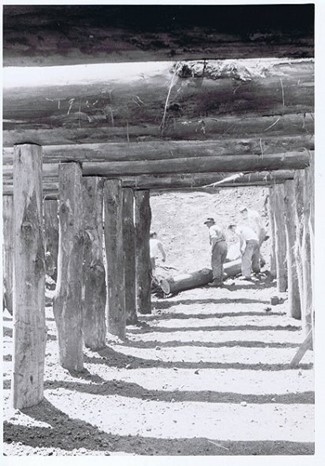

Questions of design of dugouts were debated at the hearings including ventilation, air purification, location, design (for example whether tunnel, or tunnel with cross chamber, or in flat country, shaft and drive), baffles for both for air and smoke, storage of water inside dugouts, supply of medicaments (for example for prevention or relief of temporary blindness and inflammation of the eyes), water sprays and restoratives; the direction in which the entrance to the dugout should face; the question of exposed timbers and sheet iron; and the various other suggestions which appear in the transcript of evidence.

The final recommendations of the Stretton Royal Commission included –

- The construction of dugouts at all mill settlements, and at winches during the fire danger season, should be compulsory.

- The design of the dugout, despite the test to which dugouts were subjected by the fires of January 1939, is a matter for the most careful consideration, of which only technicians are capable.

- It should be mandatory that an area of six chains in diameter, having as its centre the entrance to the dugout, should be kept clear of all trees and scrub, buildings, and material of whatsoever kind. Stores of petrol and oil, stacks of firewood and all other stores of inflammable material should be kept at such considerable distance from the dugout entrance as the State Fire Authority may decide.

And so it came to pass, the Forests Act was amended in December 1939 and dugouts became mandatory for those few sawmills that remained in forest after the 1939 fires. Many remote logging coupes and FCV roading camps also had dugouts installed.

Penalties applied for non-compliance, and the local District Forester was required to make annual pre-season inspections of all dugouts on State forests and those within the Fire Protected Area (FPA). Some were built privately on private land.

Most were primitive construction with a log or corrugated iron roof covered with earth. A hessian bag often hung at the entrance to keep the heat and smoke out. But they were dark and damp with snakes and other creepy crawlies often lurking inside.

By 1940-41, there were 19 new dugouts constructed by the Commission and a further 128 by forest licensees. Ten years later there were 8 new Commission dugouts and 21 new ones built by other interests. By 1960-61 the rate of new builds was declining but the Commission still managed 103 dugouts, while 127 were looked after by others.

However, as the forest road network improved and gave all-weather access to modern two-wheel-drive vehicles, the reliance on dugouts receded.

In 1970, the Commission built a reinforced precast concrete dugout near Powelltown to house 30 people. But the number of dugouts maintained by the Commission had fallen to 61 with another 73 by others.

According to the Forests Commission’s final annual report from 1983/84, one additional dugout was built, bringing the total number under maintenance and use to 30, along with another 14 maintained by other parties.

The use of dugouts came back into sharp focus once again after the 2009 Black Saturday Bushfires.

There are still a few remaining in the bush, but I can’t find any current official figures.