On 1 September 1939 war broke out across Europe, which was followed by the Italian leader, Benito Mussolini’s declaration of war on the 10 June 1940. Then on 7 December 1941, the Japanese Imperial Navy bombed Pearl Harbour, starting war in the Pacific.

With the renewed conflict, combined with the terrible memories of the previous war still raw, there was an outbreak of fear within the wider Australian community.

Australians felt geographically isolated and alone. They also feared invasion which led to the introduction of the National Security (Aliens Control) Act in September 1939. Importantly they overrode all other State and Federal laws.

The Australian policy was drafted in accordance with one developed in Britain, reflecting Australia’s continuing reliance on Britain during the War.

Each State applied the national regulations slightly differently, but all aliens were required to register, and their travel was restricted.

It’s important to distinguish the subtle differences between groups. Firstly, there were aliens who were permitted to remain at home, but with travel restrictions. Then there were enemy aliens who were required to register with the Civil Alien Corps (CAC). Some enemy aliens were arrested and interned in special camps, and lastly there were Prisoners of War (POW).

Unfortunately, these terms are often get used interchangeably. To add to the confusion the different categories of people sometimes lived together in the same camps.

Prisoners of war, enemy aliens and internees had different rights and authorities treated them differently. For example, prisoners of war could be forced to work, while enemy aliens working for the CAC and internees were paid for any work they did. POWs were also subject to the standards of the Geneva Convention.

Prisoners of war and internees were held in camps behind barbed wire fences and the Department of Army kept meticulous records for each person. In time, some placements to work camps for prisoners of war did not necessarily require barbed wire.

There is a common misuse of the term “internee” when discussing forestry workers. Forestry workers as a member of the Civil Aliens Corps were not internees. They were civilian aliens. Some might have previously been interned, but at the time of their enrolment in the Civil Aliens Corps they were no longer classified as an “internee”.

Men who worked in the Civil Aliens Corps were employed by the Allied Works Council which had a different reporting and administrative system, and not all records are freely available or were appropriately archived.

Many records (including those in old FCV files) as well as references, particularly those found on the internet, don’t clearly distinguish between the various categories and tend to muddle the terminology. But language matters.

Enemy Aliens and Internees.

With the outbreak of the War in Europe in 1939, and later Japan in 1941, thousands of Australian residents suddenly found themselves identified as potential threats to Australia’s national security.

The war led to panic that tens of thousands of Australian residents might become sympathisers, saboteurs or spies.

Sweeping national security laws were aimed at identifying and isolating anyone deemed by military intelligence as a security risk. There were limited rights of appeal.

It was not only Italians, Japanese and Germans who were identified, but also Greeks, Russians, French, Maltese, English and many other nationalities.

By November 1939, over 12,000 potential threats to national security had been screened by Victorian Authorities. They included:

- Men who were naturalised British subjects but of Italian or German descent, and living in Australia, could be drafted into the armed forces. They were often used as Interpreters.

- Men who were resident in Australia, but were not naturalised British subjects, had to register as aliens at the beginning of hostilities.

- Aliens only became an enemy alien when their country made declarations of war. Some were later arrested and interned, while others were required to register for the Civil Aliens Corp (CAC).

- Women and children who were identified as aliens were not generally interned unless they were seen as a particular threat.

- Enemy aliens also included some civilians and refugees who were transported to Australia by its overseas allies.

Military Intelligence grouped all aliens according to their suspected security risk. The categories broadly covered people who were suspected of espionage; or who were suspected of belonging to the Italian Armed forces; had any association with Communist organisations; or a foreign political organisation such as the Fascists; or criminal gangs such as the Mafia.

In addition, those who were involved with shipping, transport and communications, factories for war materials and any other operations with an opportunity for sabotage were included in the screening.

All leaders of influence within the Italian community, such as the Church, and all Italian males of military age were included.

Some “aliens” were interned because they were “educated” and authorities felt they were capable of leading an uprising while others who were illiterate were interned because they were likely “followers”.

Seventh Day Adventists were also swept up in the process.

Aliens were required to register with authorities and obtain permission to travel or change abode within their local police district.

Restrictions meant that aliens were not permitted to be in possession of firearms or other weapons; cameras or surveying apparatus, any apparatus capable of signalling, any carrier or homing pigeon, motor cars, motorcycles or aircraft, or any cipher, code, or other means of conducting secret correspondence.

In addition, it was an offence for aliens to speak in a language other than English on the telephone.

The regulations were divisive and encouraged the public to report suspicious activity. Many members of Melbourne’s Italian community recalled being reported for just speaking Italian by their neighbours.

Midway through the war, more than 12,000 people – mostly men, but some women and children, were held in internment camps. They included about 7000 Australian residents, including 1500 British nationals.

A further 8000 people were sent to Australia to be interned after being detained overseas by Australia’s allies. Italians and Germans arrested in the United Kingdom, Palestine, Singapore and the Malaya Straits and New Guinea were also brought to Australia for internment.

A famous group of Jewish refugees that were interned included 2000+ Dunera Boys, and about 600 chose to stay in Australia after the war. Other examples include the Vienna Boys Choir who had been touring in Australia at the outbreak of the war but were placed under the care and guardianship of Archbishop Daniel Manix in Melbourne.

The Government released many internees before the end of the war. Others could leave the camps when fighting stopped. Those from Britain or Europe could stay in Australia. But most Japanese, including some who were born in Australia, were sent back to Japan in 1946.

Civil Aliens Corps (CAC).

The Civil Aliens Corps (CAC) and the Civil Constructional Corps (CCC) were established in 1943 as a civilian labour force under the Allied Works Council (AWC).

The War Cabinet approved this step as a means of relieving Australia’s worsening manpower shortage as the war progressed. It was felt that aliens and ‘British subjects’ who were not eligible to enlist in the Australian armed forces, were a valuable labour force and as such be directed to work in projects of national importance.

The Allied Works Council took overall control of wartime projects such as construction, forestry, maintenance of camps, roads, aerodromes, railways and docks.

The Civil Aliens Corps (CAC) was established under the National Security (Aliens Service) Regulations. It was primarily composed of male refugees and enemy aliens, between the ages of 18 and 60, who were not interned, but were directed to register for work on infrastructure and defence projects.

The men needed to pass a medical and fitness test, and many were exempted on these grounds. Personal hardship was also a reason for exemption.

Many were exempted because they worked in reserved occupations such as manufacturing or farm labourers.

Overall, across Australia, less than 10% of all enemy aliens were employed by the CAC.

While being engaged in the CAC was sometimes regarded as “national service”, the enemy aliens were paid a wage. The average male wage in Victoria in 1942 was about £5 per week.

The CAC was disbanded in May 1945 and many men transferred into the Civil Construction Corps (CCC).

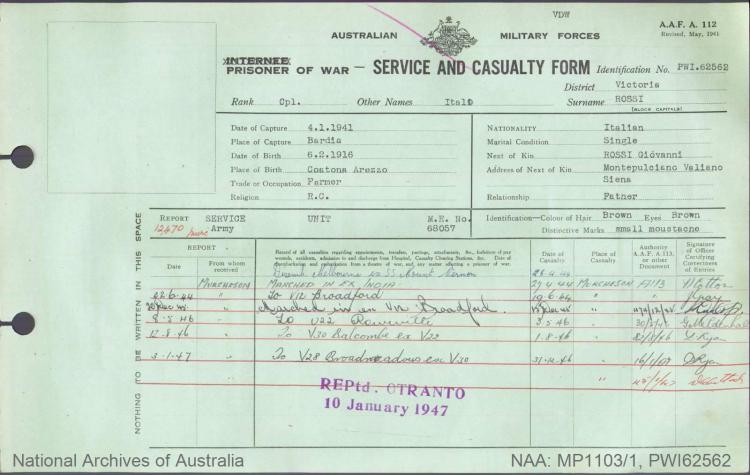

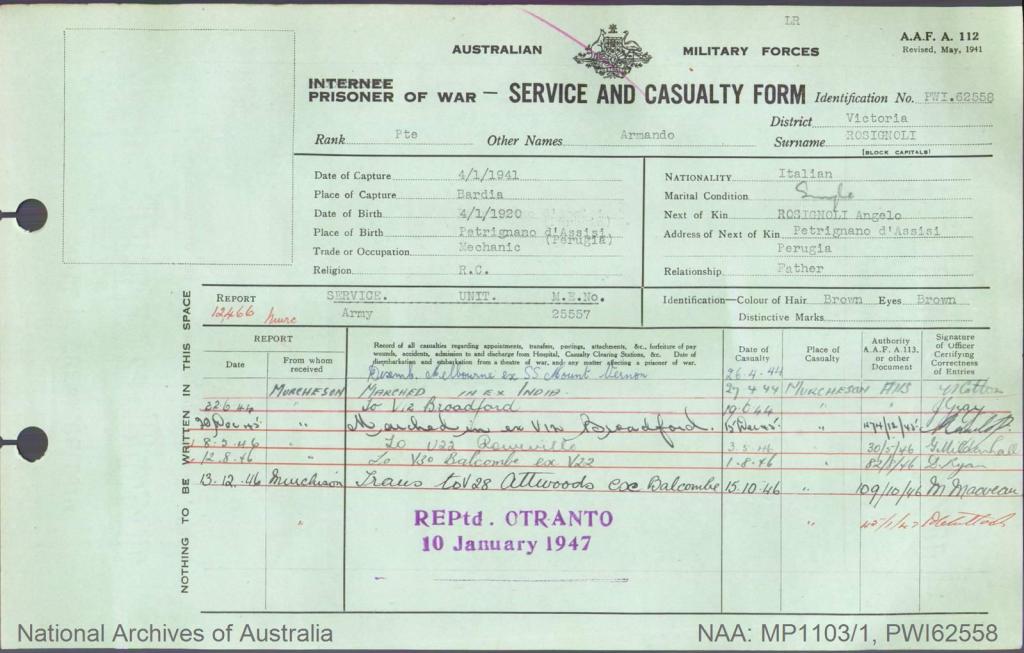

Prisoners of War (POW).

Prisoners of War (POW), unlike internees or enemy aliens, were enemy soldiers who had been captured or surrendered.

Most of the POWs initially sent to Australia were Italians and Germans captured during the North Africa campaign, in Eritrea, Abyssinia, Greece, Albania and the Mediterranean Sea.

The Italian prisoners sent to Victoria were initially held at Murchison Camp #13, which had four compounds each accommodating 1000 men.

An Italian officers’ camp was also built at Myrtleford Camp #5, comprising of two compounds for 500 men each. Myrtleford had a strong and respected Italian-community – mostly tobacco farmers and many POWs were later allowed to work unguarded in local farms.

Sailors from the German raider Kormoran, which sunk off the WA Coast in November 1941, were housed in the first instance at Harvey Camp WA, then Murchison Camp followed by a POW forest camp near Graytown, which was known as No. 6 Labour Detachment Graytown. The German officers were kept at the Dhurringile mansion

Japanese POWs captured in New Guinea were transferred through Gaythorne Camp in Queensland first, then Cowra Camp NSW, Hay Camp NSW and some were sent to Murchison Camp.

For the most part, prisoners of war were dressed in Australian uniforms left over from the First World War which had been dyed maroon. The Italian POWs complained about the colour, to be told that this was the only colour to successfully dye over khaki.

Camps.

Camps were established across Victoria. The level of security and standards of construction varied depending on the category of the inmates and the security risks.

Many were repurposed camps which had previously been used by FCV workers during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Victoria had POW camps at Dhurringile Mansion, Camp #13 near Murchison, Camp #6 near Graytown, Camp #5 near Myrtleford, as well as camps at Tatura, Rushworth and Rowville in eastern Melbourne.

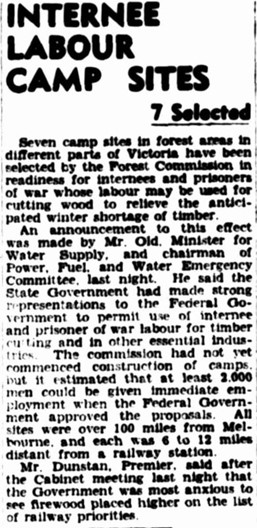

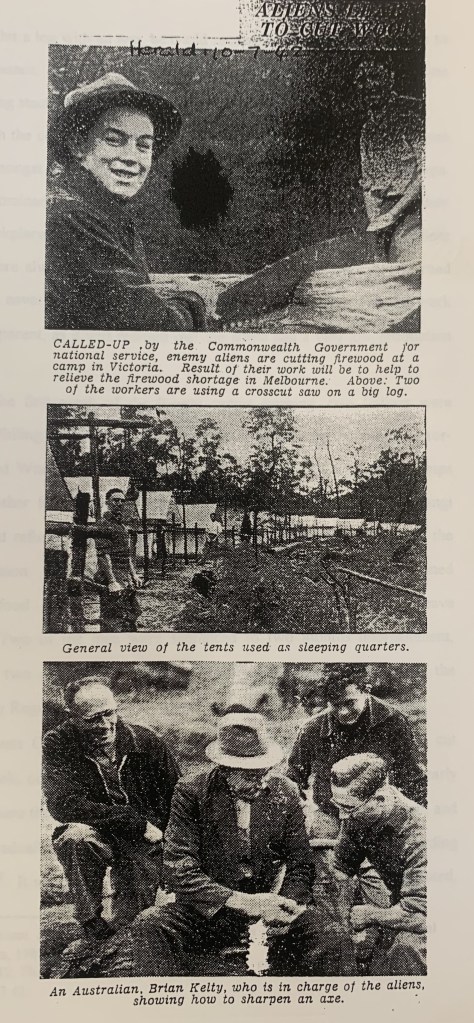

The camp at Graytown, which housed German POWs, was used to cut firewood.

Most of the higher security internment camps were in the Goulburn Valley, with two at Tatura and two at nearby Rushworth, because food was plentiful and there was a good supply of water. They were also far enough away from the coast to deter escapes.

Both POW and Internee camps were enclosed with barbed wire and had guards.

Dozens of smaller facilities without guards were also located across Victoria.

Civil Aliens Corps (CAC) workers often enjoyed more relaxed camps with Stanley Huts or tents in remote forests without fences or guards. The camps were often relatively temporary in nature.

CAC workers accrued holidays and subject to permission were allowed to take holidays. They were allowed to go into town on a weekend, though limited finances often limited this to a fortnightly or monthly visit.

Initially POWs, CAC men and Internees were housed separately, but there are many records of the groups being mixed which adds to the puzzle.

Additionally, but separately, there were also dozens of low security internment and CAC camps for enemy aliens. Together they held between 4000 to 8000 people.

There were at least 17 bush camps operated by the Forests Commission which held smaller groups of CAC workers. Over the period of the war its estimated that about 700 men cut firewood and produced charcoal to help ease Victoria’s energy shortage.

Thanks to Joanne Tapiolas for her help with this complex story.

By March 1945 it was reported that the nationalities of POWs in Australia were –

- 18,000 Italians

- 1,500 Germans

- 4,000 Japanese

There were three levels of camps –

- Prisoner of War & Internment Camp (PW & I Camp) – Administrative and Parent Camp (e.g. Tatura No 2.)

- Prisoner of War Control Hostel (PWCH) – Operated like a small camp and established for specific projects. (e.g. Broadford and Kinglake firewood camps).

- Prisoner of War Control Centre: Without Guard (PWCC) – Placement of prisoners of war on farms.

Prisoners and Internees were often moved between States so it’s tricky to give a definitive number of POWs in Victoria at any one time.

Source: Joanne Tapiolas (2019) https://italianprisonersofwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/victoria.-prisoner-of-war-camps-hostels-and-control-centres.pdf