Foresters, naturalists and the public have always remained fascinated by Victoria’s tall trees and magnificent wet forests.

But by the late 1800s, most of the giant trees reported by Government Botanist Baron von Mueller, and many others, were being rapidly lost to bushfires, timber splitters and land clearing.

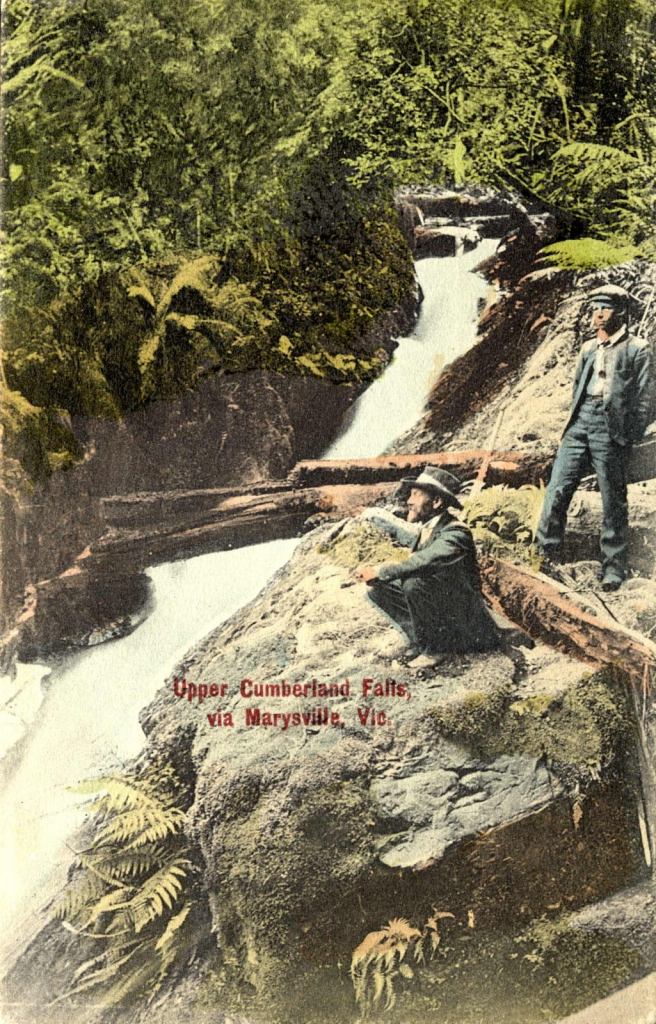

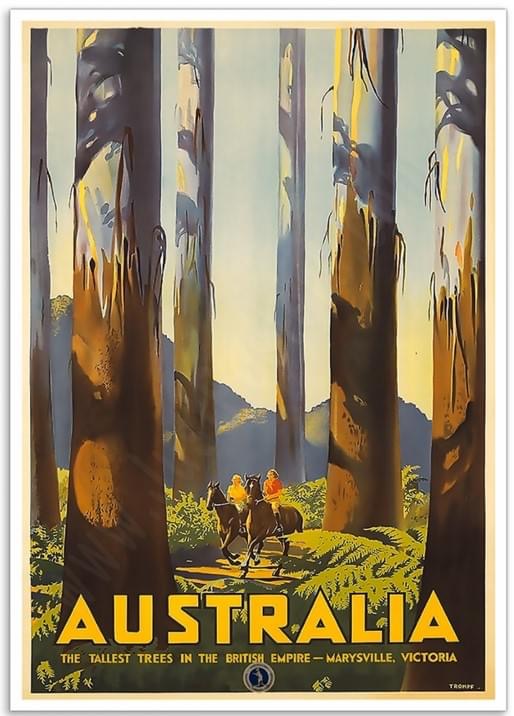

The magnificent stands of mountain ash at the head of the Cumberland Valley near Marysville had already gained an international reputation as the tallest grove of hardwoods in the world and a pristine beauty spot.

In 1896, Mr H D Ingle, then a local forester (later one of the Forests Commissioners of Victoria), often referred to the tall forests in the Cumberland Valley. Trees he claimed were well over 300 feet in height.

Nicholas Caire, famous photographer and naturalist also knew of these big trees and had named the biggest King Edward VII. It had a girth of 88 feet at 6 feet above the ground and a height of 200 feet 1 inch to its broken top. Caire photographed it in about 1907, but it was destroyed by bushfire in about 1920.

The Cumberland Valley had been cut over by timber splitters in the late 1800s and the massive trees were becoming senescent and approaching the limits of their age. They were beginning to deteriorate and fall over.

Access to the valley had always been difficult. It was situated on the old Yarra Track which went to the gold mining fields further east at Woods Point and Mattlock, but the road wasn’t suitable to transport heavy logs or sawn timber.

Various sawmillers and the Forests Commission had explored access to the upper reaches of the Armstrong Creek catchment with an extension of railways and timber tramways up from the Yarra Valley near Healesville, but the terrain and the costs were too prohibitive.

Understanding the unfolding sequence of events surrounding the Cumberland valley dispute is complex. The period coincided with considerable political turmoil. Between November 1920 and March 1935 there were several switches of Government and different Ministers for Forests, each bringing their own perspective.

- Nov 1920 to April 1924 – Alexander Peacock (Nationalist)

- April 1924 to July 1924 – Richard Toucher (Nationalist)

- July 1924 to Nov 1924 – Daniel McNamara (Labor)

- Nov 1924 to May 1927 – Horace Richardson (Nationals)

- May 1927 to Nov 1928 – William Beckett (Labor)

- Nov 1928 to Dec 1929 – John Pennington (Nationalist)

- Dec 1929 to June 1931 – William Beckett (Labor)

- June 1931 to May 1932 – Robert Williams (Labor)

- May 1932 to March 1935 – Albert Dunston (United Country)

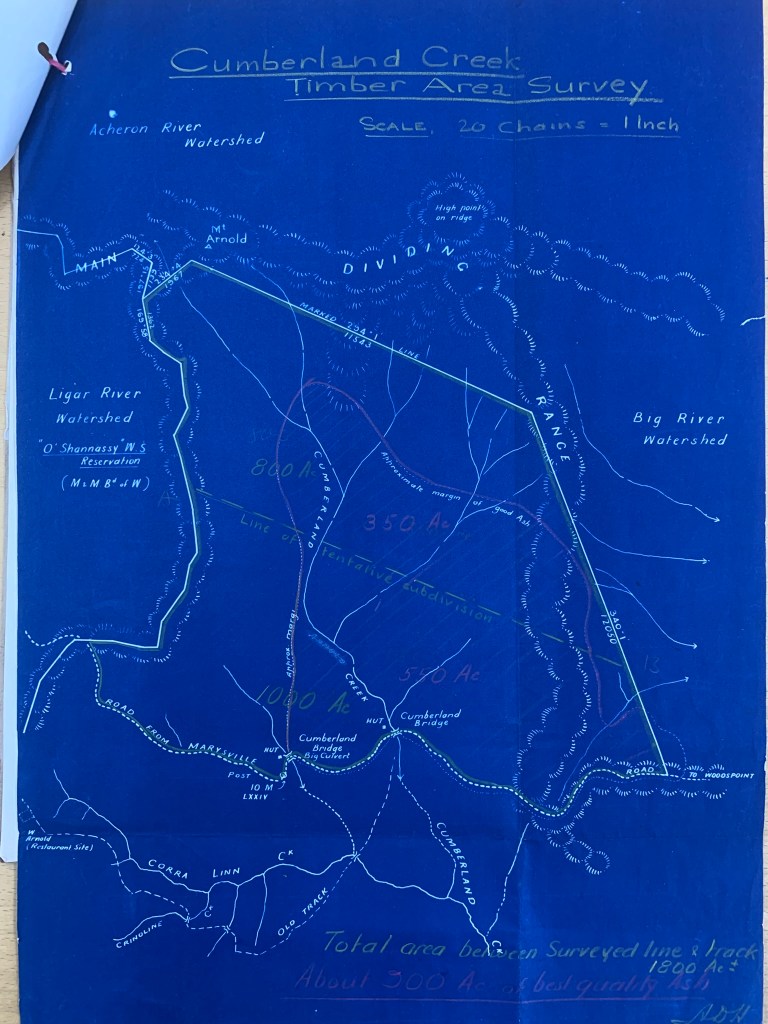

Several surveys and proposals for timber reservation of the Cumberland Valley had been considered. One of the first was by FCV surveyor, Mr Cornell, in January 1922 when he was asked by Commissioner Hugh MacKay to identify a route from the Acheron Mill site, across the Great Dividing Range, to the headwaters of the Armstrong Creek catchment.

A “blueprint” was then produced by FCV draftsman Alfred Douglas Hardy in April 1922 which identified 1,800 acres. It also highlighted the best stands of timber which were to the north of the “Big Culvert” on the Yarra Track.

With the encouragement of the Marysville Tourist Association, a small 380-acre Tourist Reserve was identified by the Forests Commission in October 1923.

At the time, the Cumberland Valley was swept up in the MMBW’s ambit claims for more closed water catchments, including the Armstrong Creek. The government was looking for a compromise to placate the sawmillers for the loss of timber.

William Beckett was both Minister of Public Health and Minister of Forests in the Labor Government of Premier Edmond John Hogan. He considered the mountain ash in the Valley as one of Victoria’s best assets.

In 1927 and 1928, Beckett moved to break the deadlock over the MMBW demand, made four years earlier, for the excision of 90,000 acres of Crown lands for water supply in the Upper Yarra. Beckett finally forced a compromise solution: there would be 45,000 acres of water reserve from which logging would be excluded, at least temporarily.

Beckett was soon besieged by deputations from all sides, particularly the Hardwood Millers Association. He soon bowed to pressure and promised to throw open all but 100-acres of the magnificent 40,000-acre old growth in the Cumberland Valley. The Minister was later embarrassed to learn that the Forests Commission had already set aside a 380-acre reserve in October 1923.

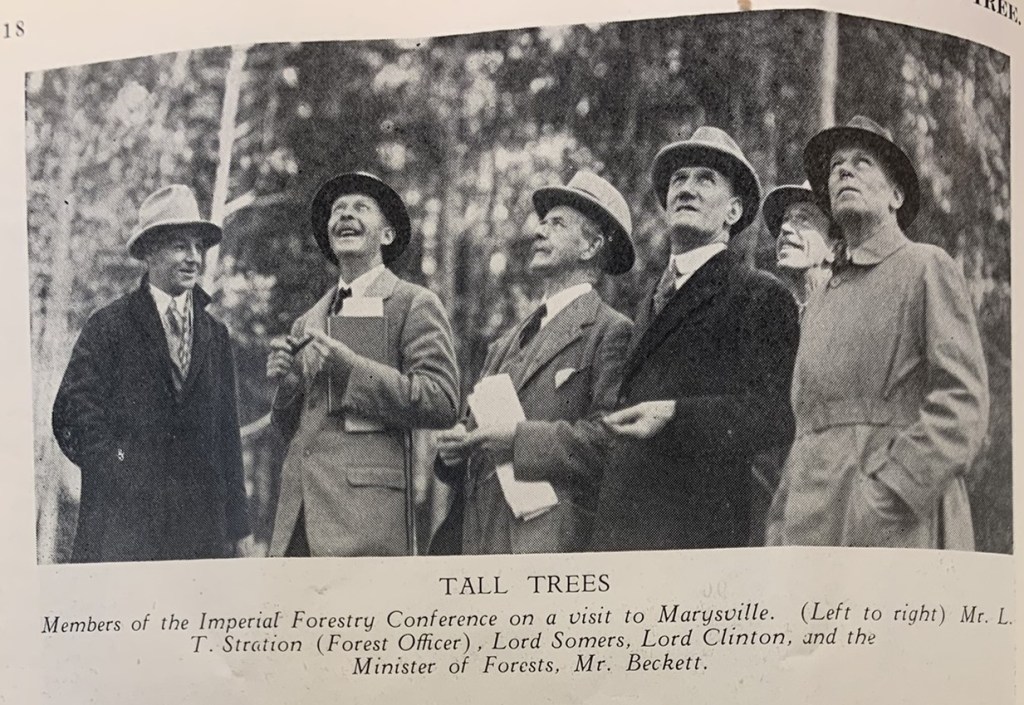

In preparation for the visit of the British Empire Forestry Conference in 1928, the Forests Commission cleared the dense undergrowth from a stand of 27 tall mountain ash trees in the Cumberland Valley, which it then named the “Sample Acre”.

The delegation visited in September 1928 and the Minister for Forests, William Beckett, accompanied them.

The former Inspector-General of Indian Forests, Sir Peter Clutterbuck, marvelled at “the finest stand of timber he had ever seen”.

There was a sudden and unexpected change in the State government in November 1928 with conservative William MacPherson as the new State Premier, and John Pennington as Minister for Forests.

Efforts continued to mount by local communities such as the Marysville Tourist Board and conservation groups led by Russell Grimwade from the Australian Forestry League (AFL), the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria and the Australian Natives Association (ANA) to set aside these forests near Marysville and protect them against logging.

Intervention by the influential Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) led by eminent conservationist Charles Barrett soon followed, and a series of well-attended public meetings in Melbourne and deputations called for the area to be declared a National Park.

Prominent individuals such as painter Arthur Streeton noted in November 1928 of the “endless beauty of the green and living forest” while Professor Ernst Johannes Hartung of Melbourne University proclaimed the Valley ought to be preserved as a rare botanical and zoological sanctuary.

The incoming Forests Minister inspected the area on January 17, 1929, and declared the Cumberland as a “national asset of inestimable value”. But in a tactical move on the following day, Pennington proclaimed a larger one square mile reservation (640 acres), to be known as the Cumberland Memorial Scenic Reserve, dedicated to returned soldiers.

Pennington then re-opened tenders for the Cumberland timber but with the added condition that all mill logs were to be felled by Forests Commission employees and sold to the successful tenderer “in the round” rather than more wasteful method of the past, “off the bench”.

A political furore erupted.

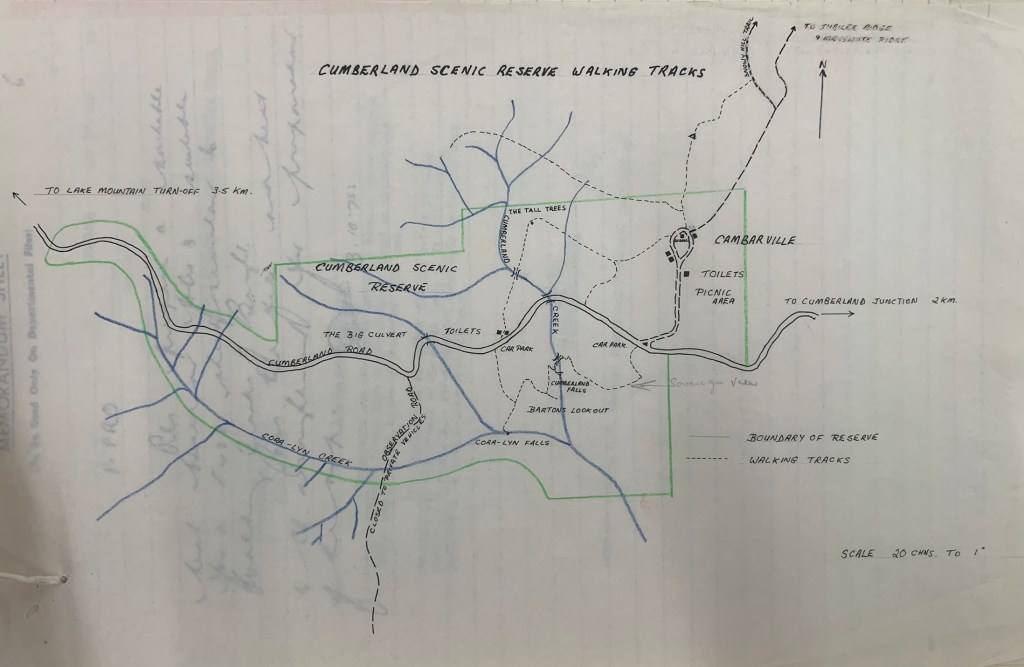

Following Minister Pennington’s promise for a larger reserve in January 1929, a survey was conducted in December 1929 by FCV Surveyor Lionel Camm, together with the local District Forester, Finton Gerraty, to identify the boundaries on-the-ground of a larger 640-acre reserve. The reserve included both the Cora Lynn and Cumberland Falls.

The 27 trees in the Sample Acre were on the northern fringe of the proposed reserve. Lionel Camm said in his report.

“The reserve included a stand of mature mountain ash sufficient ‘to give any one a correct idea of the height, dimensions and characteristics of the mature tree in its native habitat”.

With strong promotion from the Marysville Tourism Association the Cumberland Valley developed into an iconic destination for day trips and was claimed to be Victoria’s most popular tourist spot.

Signs were erected in 1935 directing visitors to the “Sample Acre” listing the dimensions of the tallest trees.

A permanent reserve of 640-acres was set aside by the Forests Commission in 1937. The Marysville Tourism and Progress Association was active on its Committee of Management.

However, the Great Depression during the 1930s, led to a fading interest in the timber in the Cumberland Valley

The road between Marysville and the Cumberland Valley was upgraded in January 1938 with a government grant of £1800. The road was not only good for tourism, but also potentially benefited the timber industry because it provided road access where previous tramway proposals had failed.

Further enlargement of the Cumberland Scenic Reserve was not supported by the Forests Commission because it claimed that “the big trees were at the end of their lifespan, would grow no bigger and when they died there would be no young forest to replace them”.

But the reserve did not placate the critics, and the dispute dragged on for more than 20 years, and was never satisfactorily resolved.

The Australian Forestry League (AFL) renewed its campaign in 1935, as part of a broader push to preserve forests and watersheds. The campaigns continued over the next four years.

The Cumberland Valley only narrowly escaped the catastrophic Black Friday bushfires in January 1939. Although fire entered the sample acre at one point.

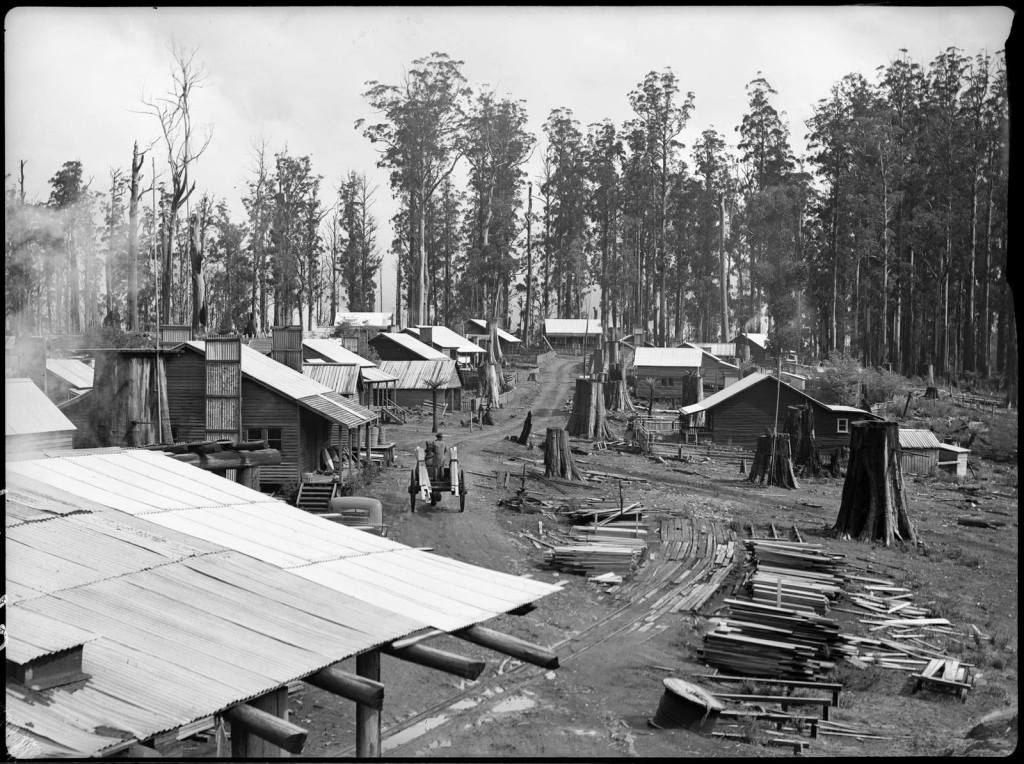

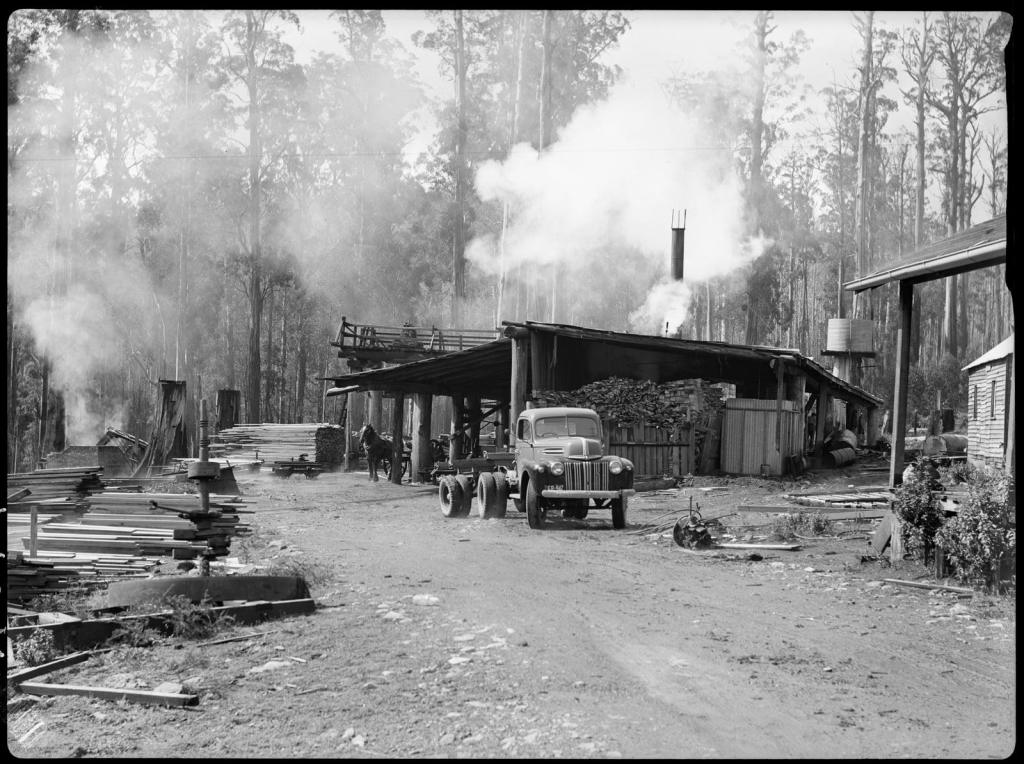

Timber salvage from the extensive fire-killed stands across the Central Highlands took the focus away from the Cumberland. A sawmill was established on the eastern edge of the scenic reserve at Cambarville, which operated until 1970.

The 640-acre area created in 1937 was formally set aside as a Scenic Reserve in 1959, under section 50 of the Forest Act. In 1974, it was extended eastwards by 70 acres to incorporate the historic sawmill site at Cambarville.

In 1968, the Armstrong Creek Catchment, which covers Cumberland Valley, was included in the Yarra tributaries lease agreement with the MMBW. Water was diverted via two small weirs near Reefton into Melbourne’s water supply.

The MMBW had concerns about pollution stemming from the Cumberland Valley and made it clear that it preferred to close the recreation area. But in 1972, the roads, walking tracks and car parks were all realigned and upgraded by the FCV. A toilet facility was also built.

John Pennington’s 1929 ambition of creating a one-square-mile reserve dedicated to returned soldiers was finally realised in 1994 with the unveiling of a plaque at Cambarville by Returned Services League President, Bruce Ruxton.

The Cumberland Valley Reserve and the site of the historic Cambarville sawmill settlement was incorporated into the Yarra Ranges National Park in 1995.

Stephen Legg (2016). Political agitation for forest conservation: Victoria, 1860–1960.

https://1drv.ms/b/c/58c25200497bbbca/Ecq7e0kAUsIggFjjHwAAAAABP0FDO0OTw4_ypKrpCPItFw?e=kgFRcu

Peter Evans (2022). Wooden Rails & Green Gold: a country of timber and transport along the Yarra Track. Light Railway Research Society.

Geoffrey Munro (1991). Cumberland Scenic Reserve, in Tom Griffiths,(ed), Secrets of the Forest, Allen & Unwin.

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3991945