Water-borne diseases were killers in all major cities throughout the nineteenth century. There was shocking news about the outbreak of cholera in Britain in the late 1840s.

Such diseases were caused by a lack of clean drinking water, together with unhygienic wastewater and sewage disposal.

Melbourne grew rapidly after the 1851 gold rush and the city initially sourced its water from wells, tanks and from a pump on the Yarra River, but this soon became hazardous to public health.

All the night soil, trade waste, as well as waste from kitchens and homes was just thrown into open channels in the street and it simply flowed wherever gravity took it… mostly back into the Yarra. The problem got so bad that some British journalists unkindly described the City as “Smellbourne”.

Responsibility passed from the City of Melbourne to the Sewers and Water Supply Commission (SWSC) in 1853, and the Yan Yean reservoir was built on the Plenty River soon after in 1857. It was Australia’s first water supply reservoir and was based on the innovative gravity-fed design of ex-convict James Blackburn.

Continued delivery of poor-quality water from Yan Yean forced access restrictions to be imposed in 1879. This undoubtedly established the precedent for the closed catchment policy of the MMBW.

The Toorourrong Reservoir, near Whittlesea, was constructed in 1883-1885 as an extension of the Yan Yean system to tap into Wallaby Creek and the upper reaches of the Plenty River.

The completion of the Yan Yean and Toorourrong Reservoirs on the Plenty River prompted a preliminary survey of the 35,500-acre Watts River catchment in the wet mountain forests east of Healesville.

The initial surveyor’s report of the Watts River was completed in 1880 and suggested two engineering alternatives. The first incorporated a large storage dam 105 feet high, while the second and cheaper option called for a low diversion weir near Healesville. Both schemes included 41 miles of aqueduct to take the water to Preston. The Watts River scheme was intended to supplement the winter supply for Melbourne while the Yan Yean Reservoir refilled.

William Ferguson was appointed as Victoria’s first “Caretaker and Overseer of Forests” in 1868 and was dispatched by Clement Hodgkinson in 1872 to assess the timber in the Watts River catchment.

He reported dense stands of tall and straight trees on the spurs averaging from 100 to 150 trees to the acre. On the rich river flats, the trees grew less densely but attained an extremely large girth, especially in the Watts Valley. He recommended that every acre in the prized Watts Valley be reserved as State forest for timber production.

Ferguson also reported to Hodgkinson, and in the Melbourne Age in February 1872, about a massive tree which had fallen across a tributary of the Watts River with an astonishing length of 435 feet from the roots to the top of its broken trunk. But many remain sceptical of this unverified claim.

The decision on the Watts River scheme was made in 1886 for the construction of a low diversion weir about 5-miles east of Healesville, along with the aqueduct to Preston. The system was officially opened on 18 February 1891.

Water was augmented from small diversion weirs and aqueducts on the Coranderrk and Donnelly’s creeks as well as Grace Burn near Healesville.

Between 1885 and 1891, all the alienated freehold land in the Watts River catchment was compulsorily purchased and the small settlement of Fernshaw on the Black Spur was removed.

The Blacks Spur Road which runs through the middle of the Watts catchment, between Healesville and Narbethong, was realigned in parts and remains one of Victoria’s premier tourist drives.

The current Maroondah Dam was completed in 1927, submerging the earlier diversion weir on the Watts River.

A Royal Commission into Sanitation was established in 1888 to address concerns about the spread of disease, particularly typhoid. The Melbourne & Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) was established with its first Board meeting on 17 March 1891, as a tangible outcome of the inquiry.

The 1890 legislation established a Board of 39 unpaid Commissioners, all drawn from Melbourne and Metropolitan Councils, with a full-time elected Chairman, Edmund Gerald FitzGibbon.

Planning the future water needs of Melbourne’s growing population became a fundamental responsibility for the new MMBW.

In a bold and visionary political move, the control of the water catchments was transferred from the Lands Department to the newly established MMBW.

The Board then announced a closed catchment policy where timber harvesting, recreation, mining, farming, grazing, settlements and all public access was not permitted, mainly as a step against the threat of disease.

Melbourne’s catchments are very unique because safe drinking water is supplied directly from closed forested catchments to customers with very little retention in storages or chemical treatment.

The deep soils and rich organic layer under the mountain ash trees also act like a giant sponge which slowly releases water over the dry summer months and reduces the reliance on storage reservoirs.

The manoeuvring over the water catchments occurred at a time when the Lands Department was still trying to alienate and sell more Crown land, the beleaguered Forests Conservator, George Perrin, was trying to save as much productive forest as possible to ensure the state’s timber needs, while the general public, and most of their elected representatives, remained largely indifferent.

Diverting additional water from 12,800 acres in the upper reaches of the Acheron River into the Watts catchment was a detailed matter for the 1897-1901 Royal Commission into Forests and Timber Reserves. The Acheron River flows north of the Great Dividing Range into the Goulburn River. The catchment had valuable timber resources, and the river was important for irrigation, and its redirection into Melbourne was too politically unpalatable for rural parliamentarians to swallow.

Interestingly, the water catchments had not been formally vested[1] in the MMBW when it was formed in 1891, a matter the Board regarded as an administrative oversight. The catchments were however included as Permanent forest reserves, and under the control of the State Forests Department in the proposed Forest Bill in 1907. The MMBW moved quickly and successfully lobbied the Premier and Ministers against the inclusion.

Furthermore, when the Forest Act was being drafted, the Board of Works insisted on the insertion of Section 16 (6) to allow for State forests to be excised for water supply purposes in the future.

A series of sequential and expansionary steps soon followed as the MMBW sought to increase Melbourne’s water supply from further afield.

The first claim was made by the MMBW in February 1908, just weeks after the appointment of the new State Forest Department, for the 32,650-acre O’Shannassy catchment.

Foresters and sawmillers were well-aware that the headwaters of the O’Shannassy catchment had some of the state’s best timber resources and together with the local municipality vigorously opposed the reservation based on economic grounds. But their calls fell on deaf ears, and the O’Shannassy was vested with the Board in 1910 and the diversion weir and aqueduct running along the contour below the Mount Donna Buang Range was completed in 1914.

The Board then lodged a renewed claim for the entire Upper Yarra catchment in April 1915, a total of 50,000 acres.

Plans were well advanced for an extension of railway lines and new sawmills to access these heavily timbered forests. The Shire of Upper Yarra, the Lilydale-Warburton Railway Trust and the State Forests Department were again livid and raised emphatic and angry protests arguing the timber harvesting and water supply were compatible.

The magnificent Cumberland River in the mountains east of Marysville was renowned for having some of Victoria’s tallest remaining trees. It was subject to a long running campaign in the 1920s to have land set aside as a scenic reserve.

The Cumberland was also on State forest within the Armstrong Creek catchment, although there was also an ambit claim by the MMBW.

The matter of closed catchments was always contentious, and the Forests Commission formally announced its contrasting policy in 1922.

The stage was set for decades of disagreement and argy-bargy between the FCV and MMBW over the closed catchment policy. But on a positive note, the debate was also the driver for some world-class catchment hydrology research.

The Commission lobbied vigorously, consistently (and mostly unsuccessfully), that timber harvesting under tightly controlled conditions was entirely compatible with the protection of water quality. It pointed out that the practice of “multiple use” was widely practiced in other rural water catchments across the State, and in other places around the world.

The MMBW was always very politically astute and well-connected, and many said it was an open secret that the Board of Works wanted to take control of all the forested catchments on the whole of the southern fall of the Great Dividing Range.

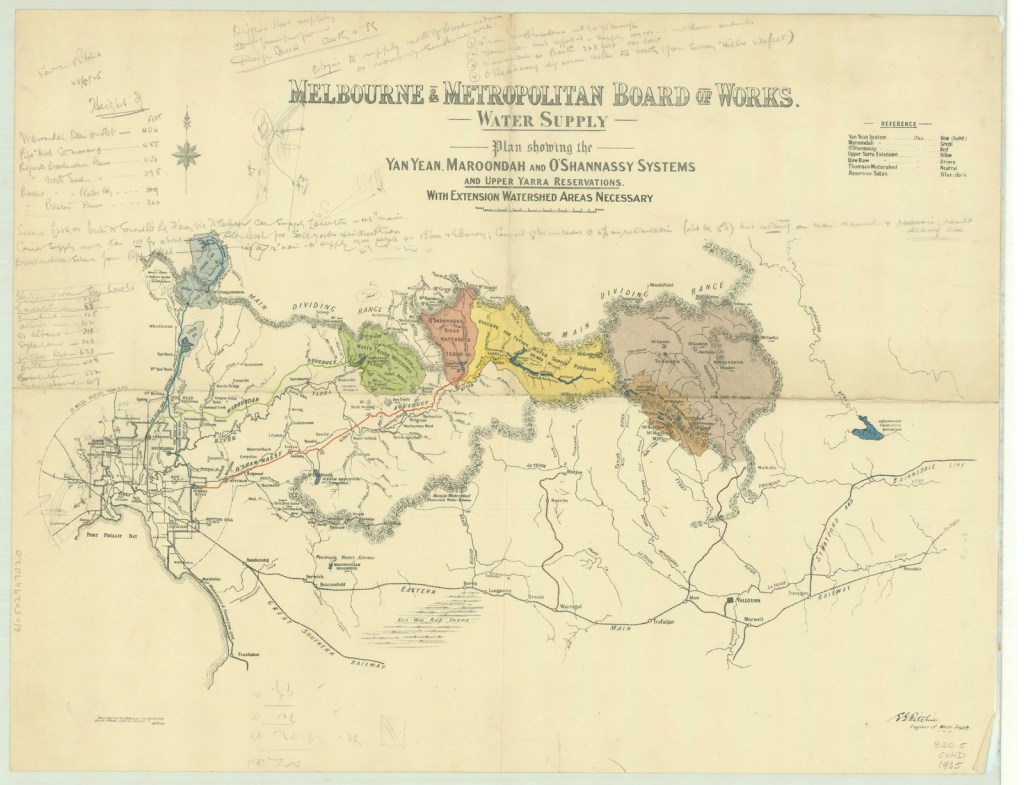

A map produced by the MMBW in 1922 unashamedly shows the Board had their eyes on the entire Upper Yarra catchment together with the Baw Baw, Thomson and Aberfeldy Rivers, which flow into the Gippsland Lakes.

The construction of the Silvan Dam in the eastern foothills of the Dandenong Ranges began in 1927 to supplement the O’Shannassy scheme and was completed by 1930. The FCV once again relinquished more State forest to the MMBW.

On completion of the O’Shannassy aqueduct earlier in 1914, and despite protest, the Board pushed ahead with its preliminary survey for the Upper Yarra reservoir which it had first identified as early as 1888.

Unlike other MMBW water catchments, the State forests in the Upper Yarra were never vested in the Board, despite the Board’s request, but were permanently transferred under lease. The MMBW gained effective control and imposed restrictions on public access. Logging was not permitted except in the buffer areas.

In 1928, the Forests Commission and the Board of Works signed a compromise agreement whereby 45,000 acres of State forest in the Upper Yarra catchment, above Walsh Creek, would be reserved for water supply with a smaller area of 5000 acres remaining available for timber harvesting on the buffers to the catchment.

In 1930, the Board changed its mind and arguably reneged on the deal. Matters became strained when the FCV engaged the Crown Solicitor who found the earlier agreement a “model of ambiguity”.

The Commission began to lobby for the right to begin logging the 5000 acres. Permission was finally granted in 1938, but the 1939 bushfires soon after, and the massive salvage operation that followed, disrupted all the Forests Commission’s previous timber harvesting plans.

Timber salvage in the Walsh Creek basin was accelerated following the 1939 bushfires but, in 1940, the Commission surrendered its remaining rights after the Board of Works offered a compensation payment for the loss of timber royalties.

However, timber was salvaged from areas to be submerged, and this was initially under the supervision of the Forests Commission, and later the Board of Works.

But then WW2 intervened in late 1939, and work didn’t resume on the Upper Yarra Dam project until 1948.

Melbourne’s population grew rapidly, particularly in the post-war period, and water demand continued to rise. The average daily water consumption rose from 53.50 gallons per head in 1891 to 76.89 gallons in 1940.

The Upper Yarra Dam wall, constructed of earth and rock fill, was the highest dam of its type in the southern hemisphere when it was completed in 1957. It tripled the amount of water impounded for Melbourne’s use.

The Dam and its associated works, such as the 6,200 foot-long Little Joe tunnel, took 10 years to complete and was the most expensive water supply project the Board had undertaken.

The completion of the Dam coincided with the centenary of Melbourne’s water supply system beginning with the Yan Yean Reservoir.

The Forests Commission continued its long campaign of opposition to the closed catchment policy of the MMBW, arguing that timber harvesting, controlled public access and the protection of water supplies were all compatible.

Between 1957 and 1960, the State Development Committee held an inquiry into the utilisation of timber resources in the watersheds of the State.

Submissions to the Committee were made by both the Forests Commission and MMBW, with the Commission once again strongly advocating for logging access to closed water catchments. It advanced as evidence its successful conduct of harvesting in many proclaimed catchments across rural Victoria. The Commission also pointed out the State was spending £10 million per year on importing timber.

The Committee recognised the importance of timber to the State and its summary report said …

“it is practicable for logging to be carried out without deleterious effects provided strict supervision is maintained over operations”.

But the Parliament had no appetite to overturn the closed catchment policy which had stood since 1891, and the status quo remained.

The Forests Commission was disappointed, but probably unsurprised, by the decision. They were more concerned that future access to the timber resources in the Thomson and Aberfeldy catchments could be restricted with the construction of any new storage reservoir.

It’s also fair to say there was a lack of scientific data to make an informed decision, so politicians were very unlikely to risk the safe water supplies for over 1.8 million people in Melbourne without compelling evidence.

The MMBW had commenced research into forest cover on water supplies as early as 1930. It included species trials with planting of Coast Redwoods and other conifers at Cement Creek.

Following the Parliamentary Inquiry in 1957-60, the Board set up an innovative series of paired catchment experiments in the wet mountain forests at Coranderrk near Healesville. They were designed to measure the long-term impacts of timber harvesting and bushfire on water quality and quantity.

It took another 10 years for the preliminary results to emerge, and there were a few key conclusions:

- timber harvesting could be carried out without detriment to water quality given good planning and rigorous implementation of prescriptions,

- the most dramatic threat to stream flows was not timber harvesting but remained catastrophic bushfires like those on Black Friday in 1939. (see Kuczera curve)

The 1960s again saw more prolonged droughts and deadly bushfires on the fringes of Melbourne.

The drought stoked growing concerns about long term water supply security, and in 1965 a Parliamentary Public Works Committee began another inquiry into future water supplies for the growing city. They reported in 1967.

In response to the Inquiry, the Bolte Government immediately approved works for a 20km diversion tunnel from the Thomson River into the Upper Yarra reservoir. Detailed planning began for the construction of the massive Thomson Dam in Gippsland to add to Melbourne’s water storage capacity.

The Inquiry also led to the construction of Cardinia, Greenvale and Sugarloaf Reservoirs, which are all off-river storages. Sugarloaf has a full treatment plant while Cardinia and Greenvale are chlorine dose only.

A diversion from the Big River, which flows into Eildon Weir, was also considered, but scuppered by the Premier on political grounds when he boldly stated that no water shall flow over the Great Dividing Range into Melbourne, (conveniently overlooking the Wallaby Creek).

In addition to the Thomson, some smaller diversion catchments known as the “Yarra Tributaries” were set aside. A 10-year lease agreement was struck between the Commission and the MMBW in 1968 to augment water supplies. Five small concrete weirs on the Armstrong Creek (east and west), Starvation, McMahons and Cement Creeks were built to divert water directly into the Silvan Conduit that connected the Upper Yarra Reservoir to Melbourne.

All the newly designated Yarra Tributaries, as well as the Thomson Catchment, were on State forest, unlike the vested MMBW water catchments. They were partly closed to public access and some gates were erected, but timber harvesting continued with some additional protections.

Construction of the new Thomson Dam commenced in the early 1970s and was completed in 1984.

The debate about closed water catchments subsided during the 1970s and 1980s, and when most of the land was incorporated into the Yarra Ranges National Park in 1995, the long running argument about timber harvesting evaporated.

[1] “Vesting” is the formal legal process of committing, or dedicating, Crown land to statutory authorities like the MMBW for public purposes and involves a notice in the Government Gazette.

Williams, David (2024). The Forests Commission’s Role in Catchment Management.

Peter Evans (2005). The Great Wall of China: Catchment policy and forests beyond the Yarra watershed 1850-1950. Proceedings 6th National Conference of the Australian Forest History Society Inc.

Report number 13 of the Royal Commission on State Forest and Timber Reserves (1900). Proposed Diversion of Water from Upper Acheron for Supply of Metropolis, and question of vesting catchment area in Metropolitan Board of Works.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1BagaOOElDdsaZgViMjdy_RI_E_KZNr-6/view

[1] “Vesting” is the formal legal process of committing, or dedicating, Crown land to statutory authorities like the MMBW for public purposes and involves a notice in the Government Gazette.

Top Image: The original diversion weir on the Watts River near Healesville was completed in 1891 but is now submerged under Maroondah Reservoir. Source: SLV http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/289212

http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/120587

Thorough, as always. The discussion of harvesting to manage bushfire threat, coupled with timber production, still continues amongst professionals in the water industry; however, it’s quashed in Victoria by politics.

LikeLiked by 1 person