By the time of the formation of an independent Forests Commission in 1918, the area of Victoria’s Reserved forest estate had stabilised at about 4 million acres.

All forest experts and enquiries said this figure was far too low for Victoria’s future timber needs and it was claimed that a minimum of 5.6 million acres of productive and accessible forest were required.

Most of the state’s remaining public land was designated as unalienated Crown land (e.g. Protected forest) and was still subject to sale by the powerful Lands Department.

But there was still strong resistance for more forest reservations by those in government and by those interested in gaining more land for grazing and agriculture, and unfortunately there was general public apathy.

Perhaps foreseeing a threat to the fragile integrity of reserved forest estate in a post war reconstruction period, Hugh MacKay wrote in the 1917-18 annual report –

- It is my duty to call attention to the danger which will threaten the existence of many of the most valuable forest reserves on the northern plains during the coming period of repatriation [of soldiers]. Scattered over a wide expanse of country between Horsham and Chiltern, they afford there the only safe supplies available of fencing timber and fuel for future years. They bear in quantity, in addition to other species, grey box and ironbark, two of the most useful and durable of Australian hardwoods and as a source of supply of railway timber alone their permanent retention as forest is essential…

- It would be an incredible folly after the period of forest destruction which culminated in the ruin of the Otways, of the Moormbool box forest in the Heathcote district and of the Gippsland red gum forest

Following the end of the War almost 78,000 diggers returned home to Victoria.

Soldier Settlement Schemes were designed to provide some of these returned soldiers with a livelihood. It was also a reward for their service. The patriotic notion of “Yeoman Ideal” and of a “land fit for heroes” resurfaced with a promise of prosperous farms, secure families and thriving rural communities.

The Land Act (1898) gave power to the State government to compulsorily purchase portions of large land holdings and sell or lease that land in smaller parcels for farm development.

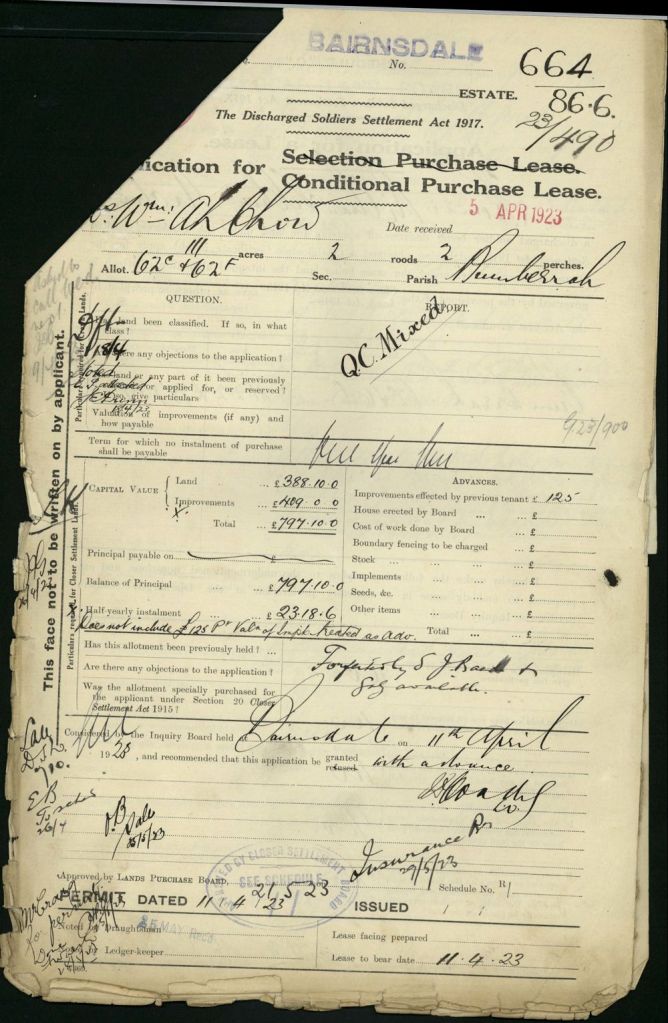

Under the Discharged Soldier Settlement Act (1917), Crown land could be made available for settlement but, as it turned out, much of it was purchased, subdivided and resold.

The scheme was first administered by the Victorian Lands Purchase and Administration Board and, from 1918, by the Closer Settlement Board.

Settlements were established in the dryland farming areas of the Mallee, South Gippsland and the Western District, and in the irrigation areas of the north-west along the Murray, central Gippsland near Maffra and Sale, and the Goulburn Valley.

In addition, the British Government passed the Empire Settlement Act in September 1922, which promised 10,000 migrant settlers for Victoria over the next five years.

By 1930, the Victorian Government had acquired 2.5 million acres and about 12,000 returned servicemen had taken up the scheme.

Low interest finance and no repayments for the first 3 years on 36-year purchase leases were introduced for the settlement of discharged soldiers. From 1922 assisted British immigrants were also settled on the land as part of the Closer Settlement schemes.

Few had seen their block of land before they bought it, and only 20% had any farming experience. It was lottery and some soldier settlers were lucky enough to secure a good block. Some farms remained free from the ravages of pests and disease, but none could escape the plunge in farm commodity prices in the 1920s.

By 1926, nearly a quarter of the soldier settlers had walked off their properties. A Royal Commission in 1925 had identified many shortcomings of the schemes especially the marginal land such as the Mallee and recommended against settlement in future.

Perhaps one of most notable returned servicemen who later worked for the Forests Commission was Bill Ah Chow. He attempted to settle with his wife Myrtle at Mossiface near Bruthen and worked the land for three years, but the shoulder injuries he sustained in the war made farming too difficult.

With his extensive knowledge of the local bush, Bill was offered a job by the District Forester, Jim Westcott, as a Fire Guard and famously built Moscow Villa on Bentley Plain in 1942.

Soldier settlement schemes were revisited again after WW2, most notable at Heytesbury in western Victoria.