“One of the grandest public estates in the Colony”.

Conservator George Perrin – 1894.

The European settlement of the Red Gum forests along the Murray River, like many other places, followed the initial routes of early explorers such as Hume and Hovell, Charles Sturt and Major Mitchell.

Despite attempts by the NSW Governor to restrict land settlement to 19 counties around Sydney, the squatters soon established pastoral runs.

In December 1840, Edward Curr, a Tasmanian merchant and landowner, acquired a sheep run near Heathcote. With the help of his sons, Edward and Thomas, they took up several additional runs.

To overcome the problem of summer grass they selected a tract of country on the south side of the Murray River known as Moira. The forests were flooded for several months during the winter and spring but then flourished over summer with excellent sheep fodder.

Red Gum seedlings are sensitive to fire and the openness of the forests may have been explained by indigenous burning.

The Curr’s were soon joined by other pastoralists, and by the mid-1840s the Red Gum forests at Barmah were surrounded by other squatters.

Efforts by Governor Gipps in 1844 to tax the squatters were strongly opposed and eventually thwarted in both Sydney and the Colonial office in London. The pastoralists were then left in control of one of the richest grazing and forest assets of the Colony at ridiculously low prices.

A one-square-mile, or 640-acre, “Presumptive Right” was granted to Roderick McDonell in February 1854 to surround his small farm, slab hut, stockyards and stable at Yielima, and remains a legacy of the pastoral era.

The discovery of gold at Bendigo and Ballarat in 1851 increased the fortunes of the grazier’s by supplying the miners.

A railway line was extended beyond Bendigo to Echuca in 1863 and sleeper cutters fanned out across the nearby Red Gum forests. Collier and Barry were the main contractors, but they closed the mill when the railway was completed in 1864.

With the new railway line to Melbourne, Echuca developed into a thriving inland-port, and by mid-1865 a fleet of 26 paddle steamers were working the Murray River plying the profitable wool trade.

In the 1860s, durable species like Red Gum was in big demand for the construction of wharf piers and for export to India for railway sleepers and construction timber. As Bendigo’s quartz mines began to go deeper and deeper, red gum was found to be an excellent timber for the slabbing of shafts.

The later expansion of Victoria’s railways under the notorious “Octopus Acts” of 1880 and 1884, once again fuelled the demand for sleepers, and at least six millers were at work in the Red Gum forests.

Interestingly, the sleepers were cut in spot mills rather than hewn with axes, which was a very wasteful practice, and one which the Forest Conservator, George Perrin, had continually fought the railways over.

Some of the first mills were established near the Goulburn River junction and Collier and Barry in 1863 and James Macintosh, a migrant from Elgin in Scotland in partnership with Amos and Taylor. After a flood in 1867, Macintosh bought out his partners and shifted his Goulburn Junction mill to Echuca East in 1868. Five or six other smaller mills also located there.

The competition between sawmillers was unscrupulous and cutthroat. It was alleged that in the mad scramble to access the best timber, millers attempted to exclude newcomers by sending gangs of men to new sawmill sites, where they would fall and brand all the available trees, regardless of their condition or size, and make no attempt to remove them.

As the timber trade in the Barmah forest expanded, the mills of James Mackintosh and his competitors in Echuca evolved into vast and complex industries. In 1873, Mackintosh’s Echuca East works consisted of sawmills, offices, stables, a blacksmith shop, Mr Macintosh’s substantial home, and houses for his employees. A tramway had also been laid down from the river to the mill.

James Macintosh was not only a pioneer entrepreneur of the red gum trade, he was also, a prominent local citizen, a Borough Councillor and Mayor, as well as an elder of the Presbyterian Church. The unusual memorial archway in Echuca made of Red Gum was erected by Macintosh to honour the visit of the Colonial Governor, Sir Henry Brougham Loch, in 1884.

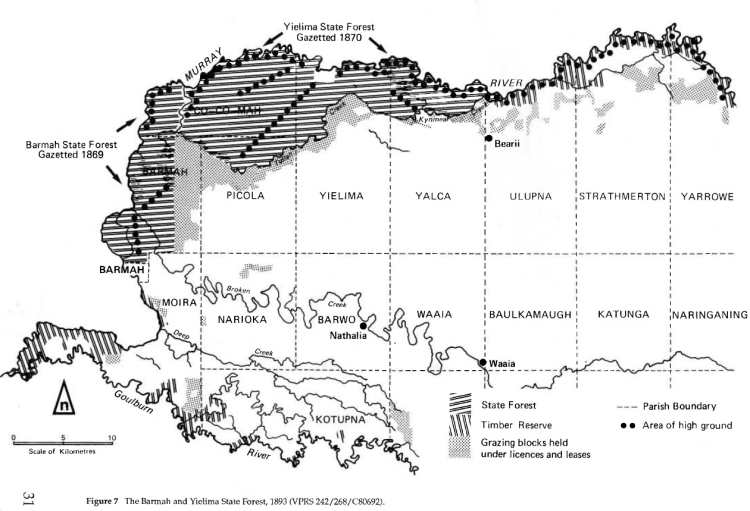

As early in 1869, Crown land bailiff, Henry Stephenson, warned his superiors of the impact of over cutting of the forests. He pointed to magnificent stands of tall and straight trees which still remained. He strongly advocated for the creation of the Barmah Timber Reserve and in July 1869 some 19,600 acres was proclaimed.

Just one year after Stephenson’s report, the newly appointed “Overseer of Forests and Crown Land Bailiff, William Ferguson, wrote of the riches of the River Red Gum reserves and pointed out the threats to his senior officers in Melbourne. These included the Assistant Commissioner of Crown Lands and Survey Clement Hodgkinson, and Baron Von Mueller.

In many places he counted 80 to 100 trees per acre, upwards of 60 feet tall and 18 to 20 inches in diameter. Great preparations, he warned his superiors, were being made for hewing down the best timber and sending it to India. Already huts had been erected, and preparations were being made to bring portable steam engines into the forest.

Ferguson concluded that:

“with proper care and protection these forests on the Murray may be made available for generations as they are magnificent nurseries for young trees which are now being so ruthlessly destroyed.”

Ferguson’s advice was acted upon with the proclamation of the Yielima State Forest in July 1870, which brought the total area reserved to roughly 45,000 acres. The Lands Department to ceded to the request because the Barmah forest was flood prone and not suitable for alienation into farmland.

Timber harvesting was permitted in the State forests but mechanisms to regulate it was full of loopholes and there were few foresters on-the-ground to enforce them.

Clement Hodgkinson then attempted to regulate the sawmillers in 1874 by restricting cutting areas to 5000 acres, to give the forest a chance to recover. But the opposition from millers, some rural politicians and the local press was too strong, so the plan was shelved.

A local Forest Board was proposed for the Red Gum by Premier James McCulloch, river boat owner and later sawmiller. Legislation to create the Boards had been enacted in 1871 and was intended to give Boards the power to grant licences, to manage and control Timber Reserves, to appoint bailiffs, to conduct prosecutions, give penalties and collect moneys.

But many observers felt that the power and local influence of sawmillers, particularly James Mackintosh, made it unwise to establish a local board for the Red Gum forests. A change of government in 1877 scuttled the idea altogether.

In its almost unregulated state, the Red Gum trade continued to expand. In 1875, it was estimated that seven sawmillers in the Echuca district alone employed almost 400 men and cut almost 400,000 superficial feet of timber from 1000 logs per week.

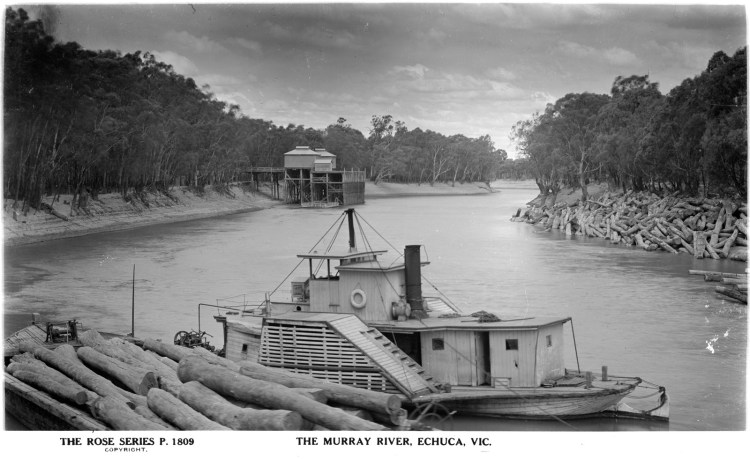

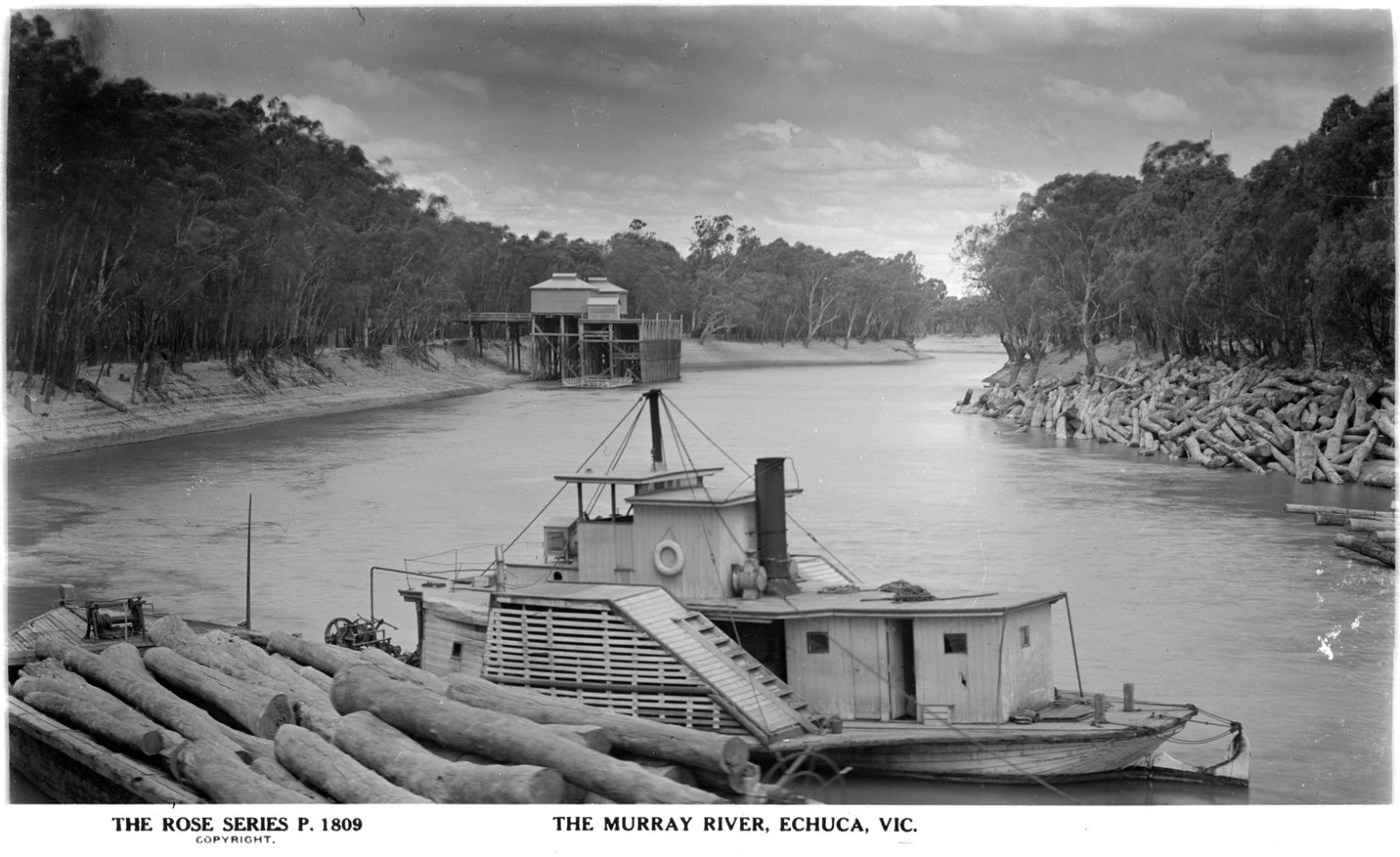

The annual winter flooding of the forests impacted the pattern of timber harvesting and transport. When the forest dried out in spring, logs were cut and taken to the banks of the Murray River by bullock or horse teams and waited to be loaded onto barges and towed or floated downstream to sawmills. Some of the logs were stockpiled on the banks of the river near Echuca.

In 1873, Mackintosh owned two steamers, the Enterprise and the Julia. It’s said that he was the first sawmiller to use river transport to bring the logs to a mill with log barges which could carry 40 tons or about 30,000 super feet.

Barges were either insiders or outsiders. Logs were either placed inside the barge or chained below the out-riggers hanging across the gunwales.

The famous Paddle Steamer, Hero, later to be owned and operated by the Forests Commission during WW2 to solve Victoria’s fuelwood crisis, was launched from Mackintosh’s sawmill in September 1874.

Steam engines were also used to operate small portable spot mills in the bush to cut logs from the late 1800s until the 1940s.

In November 1877, in an effort to regulate cutting and conserve young forest regrowth, the Red Gum trade took another hit when the Minister for Trade and Customs Peter Lalor (of Eureka Stockade fame) announced a duty of 10 shillings per 100 super feet would be levied on timber exported to other states and overseas. Sawmillers and contractors protested loudly as their markets collapsed overnight.

Alexander Robert Wallis, Secretary of Agriculture and member of the Central Forest Board, was sent to investigate the complaints. His scathing report from 20 July 1878 justified the Government’s stance as he witnessed for himself the forest devastation. He estimated that only 4 to 6 years of timber remained, but that careful controls could ensure that the forests were not exhausted.

Unsurprisingly, the locals strongly disagreed with Wallis’ assessment. In August 1878, the local MP, Duncan Gillis, claimed that nearly 1,000 people were unemployed as a direct result of the duty.

Sawmillers and mill workers reacted swiftly by organising protest meetings against the Government and deputations were made directly to the Premier, Graham Berry.

The Government capitulated and suspended the duty for a year from August 1878. But they required millers to enter into bonds to pay the duty if the legislation was reimposed. A long period of uncertainty followed. The duty was suspended twice more, before being finally repealed in August 1881.

The economic depression of the early 1890s, together with the crippling state tariffs, forced James Mackintosh into liquidation. Other sawmillers either amalgamated or closed.

The industry had been brought to a standstill. Where 14 mills had been hard pressed in 1877 to cope with demand for sleepers, only 3 mills remained by 1881.

The Red Gum trade had seen its greatest days.

However, Richard James Evans, who came to Australia from Wales, then founded a sawmilling firm in Echuca in 1899. The mill was moved to the present site near the wharf and current historic precinct in 1923. The Evans Bros. also owned and operated the paddle steamers Edwards and Murrumbidgee, which were used to transport of logs until 1956. Three “outrigger” barges were named Alison, Impulse and Clyde while two “insider” barges were named Ada and Whaler.

In 1892, it was then pointed out to the Colonial Government that while Victoria granted the right to cut Red Gum at nominal fees, across the River in New South Wales a royalty of 12/6 per 1,000 superficial feet was charged.

Under this arrangement a sawmill in Echuca obtained 1,600 logs at Yielima for the payment of 31 pounds while the same number of logs obtained from across the river in NSW would have generated a royalty of 700 pounds.

To prevent excessive cutting of the Victorian Red Gum, the State Government was forced to follow suit, and in 1892 a royalty of 5 shillings per 1,000 super feet was introduced.

One of the only other active measures for maintaining the Forest was the thinning of 15,000 acres by unemployed workers in 1892, under the direction of the Conservator of Forests, George Perrin.

The Royal Commission on State Forests and Timber Reserve reported critically in 1899 on the state and management of the Barmah and Gunbower forests.

The Royal Commissioners also noted that the River Red Gum forests were under the supervision of only one forester, who was stationed near Barmah. His duties were to patrol the reserve from end to end (a distance of about 70 miles); measure logs for the sawmills and assess royalty; and supervise the sleeper hewers, who were at work along the course of the Goulbum River. Grazing in the forest also received their critical concern, which echoed Perrin’s earlier complaints.

Following the formation of the State Forest Department in 1907, and later the Forests Commission Victoria in 1919, foresters attempted to put controls on the previously haphazard and wasteful cutting of timber.

The Commission was able to put greater focus on producing a sustainable level of harvest of sawlogs and sleepers, better silviculture to regenerate and thin the forest, regulating flooding, better licensing of grazing and apiary, building roads and controlling bushfires.

Rather than the previous unregulated arrangement of “sawmiller selection”, the bush was assessed by an authorised forest officer and individual trees blazed on the trunk and given a “toe brand” at the base with a hammer featuring a crown and an identifying number before being felled. Cut logs and sleepers were also branded by the local forester and measurements recorded for the payment of royalties.

Priority was given to producing mill logs from the main trunk. The head and spreading branches, as well as inferior shaped trees, were then cut for sleepers, strainers and fence posts.

Sleepers were first cut into nine-foot lengths then split into billets which were squared with a broad axe and adze. Tall and straight trees produced by thinning were used for posts, piles and poles. Firewood and wood for charcoal was cut from the residue.

From 1945 onwards, the availability of ex-army blitz trucks and tracked diesel tractors to load logs progressively replaced the paddle steamers on the river.

From about 1950, petrol chainsaws and swing saws increased the speed and output of cutting.

Following deliberations of the Land Conservation Council, the Barmah State Park was proclaimed in 1987 which continued to permit timber harvesting and cattle grazing. It was later legislated as the Barmah National Park in 2010.

Source: Charles Fahey (1988). Barmah Forest. A history. CFL Historic Places Branch

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1GpnPhkTf-9kettUVLkj9VwCN10dWgtF7/view

Thank you for putting together this dispassionate documentation of timber getting of red gums around Echuca. The mind boggles and the heart keens.

LikeLiked by 1 person