The political jousting over the alienation and sale of Victoria’s valuable Crown Land estate began many years before the Colony separated from NSW in 1851. It continued unabated over the following decades as self-interested and wealthy squatters (pastoralists), who dominated the Upper House of Parliament, were fiercely pitted against those keen to see a home on the land for ex-miners and working-class families.

Many of the “mining members” in the Victorian Lower House were among the most radical of parliamentarians, attacking the privilege of the Legislative Council, and giving support to land reform, tariff protection, and payment of members. Their long tradition of militancy could be traced back to the anti-government unrest on the goldfields which sparked the Eureka Rebellion in 1854.

Loopholes in the many well-intentioned Land Acts of the mid to late 1800s had progressively allowed the squatters to claim the best of the available agricultural land, particularly on the open plains of the western district.

The consequences of the Land Act (1869) were so unsatisfactory that a Royal Commission was held between 1878 and 1879.

But still the political push continued from those in the Lower House of Parliament to make more agricultural land available for the yeomanry.

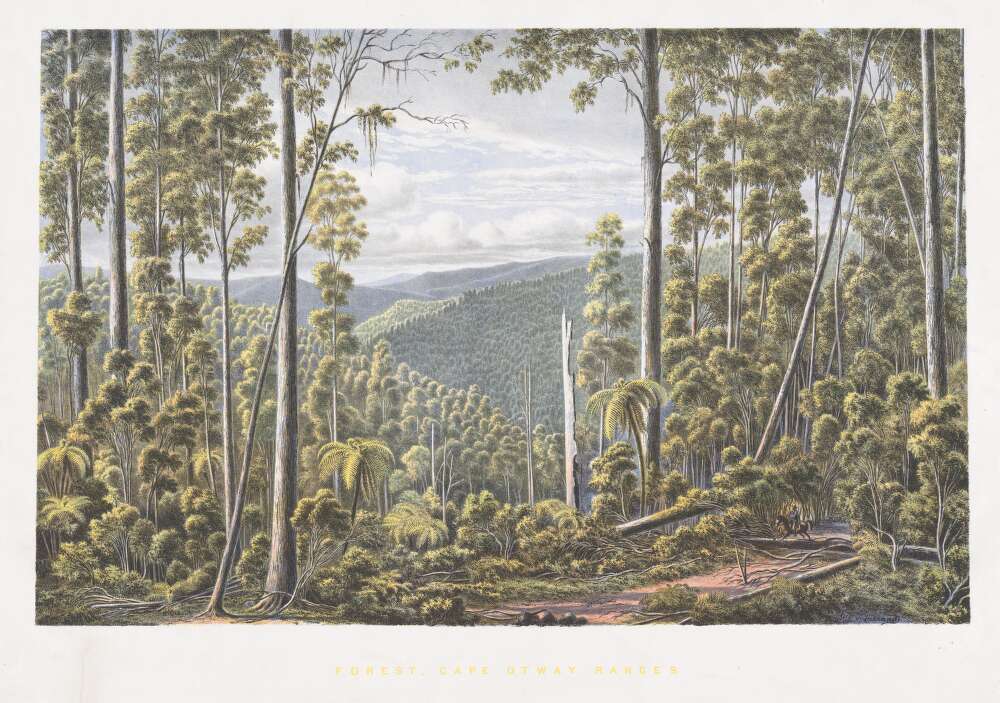

The unmapped forests of the rugged Otways and eastern Strzelecki Ranges, along with the steep mountains of the Victorian alps, and the remote forests of far-east Gippsland, had been largely ignored by the Lands Department. Prospective settlers had also avoided these areas because they were too far from markets, the terrain was too difficult, and the forests were too thick.

Settlement had begun in the foothills of the Otway ranges as early as the 1840s, but by the mid-1870s there were only about 100 selectors.

In 1873, the Minister for Lands set aside 193,000 acres as a Timber Reserve, but after a heated public debate and a change of Minister in 1879, virtually all the Crown land in the Otways (apart from a 36,000-acre tract around Cape Otway, and land which had already been selected) was made available. Blocks were surveyed and put up for selection and the available land around Apollo Bay, which had access to the port, was taken up immediately.

The Land Act (1884) and subsequent Land Act (1890) were the last of the nineteenth-century legislation to make large tracts of unallocated Crown land available for small-scale farming.

Matters came to a head in the 1890s when a severe economic recession hit Melbourne after the heady days of the goldrush.

Many state politicians believed that rural Victoria offered better opportunities for families, but most of the easier farming land had already been selected.

Besides, new settlers in the 1890s had fewer choices so moved into the remaining unalienated Crown lands in the Otway and eastern Strzelecki Ranges. At the same time, large parts of the Dandenong Ranges Timber Reserve, which had previously been set aside in 1867, were revoked in 1893 by the Minister for Lands, John McIntyre, to allow for more settlement. He later justified the decision with this explanation.

“I acted on the principle that men upon the land were better than gum trees”.

Once again, rather than tackle the stranglehold of the squattocracy, the reservation of State forests from alienation to protect valuable timber resources was sacrificed to political expediency.

Ahead of the new wave of Melbourne settlers was the Herculean task of clearing the giant trees and trying to get their produce to market on soggy or non-existent roads.

The Land Act required genuine or bonafide selectors to annually “improve” the land by clearing and making improvements, while some more unscrupulous settlers acquired the Crown land to simply cut down all the trees and sell-off all the timber, leaving a stark and denuded landscape. But, either way, the forest was destroyed just the same.

The rainfall was higher in the dense mountain ash forests, and it was wrongly assumed the land was fertile because of the giant trees that grew there. It proved to be a disaster.

The deadly bushfires, the indiscriminate clearing of Victoria’s public land, and the wastage of its forests and timber resources during the 1800s could no longer be ignored. In late 1897, the State government gave a very wide-ranging brief to a Royal Commission to examine the destruction of the State’s native forests.

The Commission, which sat for four years until 1901, produced 14 separate reports, which are remarkable both in their scope and for their careful description, mostly for the first time, of the principal forests of Victoria together with their condition.

It is equally astonishing how far timber getting had extended into the Victorian bush over a period of less than fifty years since the discovery of gold in 1851.

The Otway Ranges Report was produced in 1899 and describes the magnificent wet forests and how they once contained extremely valuable and high-quality mountain ash, blue gum, messmate and blackwood – perhaps the finest forests in Australia.

But the Otway forests were rapidly succumbing to pressures for land selection. The tragedy was that much of the best forest country was on relatively steep land with high rainfall and a short growing season so that it was not well suited for agriculture.

The destruction of mountain ash and blue gum in the Beech Forest area was appalling. On scores of land selections trees with a height to the first branch from 120 to 200 feet were ringed barked. The ringing work was valued by the Lands Department as an improvement at 3/- an acre. But sawmillers in the district were appalled at the wastage and considered the value of the timber destroyed “would have paid the national debt”.

Immense quantities of magnificent young timber were also destroyed by the 1898 bushfire.

The story of land alienation in the Otways set-out in the Royal Commission report reveals an extraordinarily confused saga –

“In the year 1879 the temporary reservation of the eastern area of 193,000 acres was cancelled with the object of making certain lands in the Apollo Bay district available for selection, about 36,000 acres only of the southern portion being retained. In 1886 Beech Forest was thrown open for selection. In 1890 such portions of this extensive tract as were unoccupied by the bona fide selector or the speculator were withdrawn from further selection on account of the value of the timber but were again made available for settlement in April 1893. In December of the same year and again in 1895 the western part of the area (36,000 acres) at the extremity of the Peninsula known as the `Otway State Forest’ and containing 18,000 acres, was thrown open for selection”.

The report also suggested –

“It is doubtful whether in any other part of the colony there is to be found such a variety of valuable timber trees as in the Otway peninsula”.

It also found that settlement in the Otways had been a –

“great administrative blunder and that most of the timbered areas should have been reserved for timber harvesting and water supply”.

The conclusion of the Royal Commission report on the Otway Ranges, was that in the short space of fifteen years immense tracts of the finest forests in Australia had been devastated by axe and fire in the pursuit of settlement.

It was the same story in the eastern Strzelecki Ranges which became known as “The Heartbreak Hills”, where many families simply walked off the land.

Voices opposing the wasteful clearing, such as from the Conservator of Forests George Perrin, went unheeded by the powerful Lands Department.

As early as 1887, the Minister for Lands, John Dow, had been expressing regret that the magnificent blue gum ridges throughout south Gippsland had been alienated by the Crown and that

“every acre of this land has passed into the hands of private selectors”.

The 1897-1901 Royal Commission into the destruction of the state’s native forests proved a significant turning point in forest conservation in Victoria.

However, another push for alienation in the western Otways in the early 1920s, led by the Minister for Lands David Oman, was successfully rebutted by the Forests Commission, but at the expense of the new FCV Chairman, Owen Jones.

But the great irony was that large areas of these wet forests in the Otways and Strzelecki Ranges were, at great expense, reforested and replanted by the Forests Commission and private forest growers from the 1930s onwards.

https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2015/reading-papers