As gold revenues declined, selling Crown Land to accommodate the thousands of new arrivals on farms and settlements became the next untapped frontier of wealth for the new colonial government.

Producing enough food for the expanding population was another important consideration.

Besides, farming was believed to provide a “healthy and pleasant pursuit” for ex-miners who might otherwise become “discontented and dangerous to public safety”. For many Irish immigrant families (like my own), who had been driven from their homeland by the potato famine, poverty and repression, a new life in agriculture in Victoria presented a more attractive alternative.

“Yeoman Ideal” was a popular and romantic belief in the worthy and noble figure of an enterprising and independent family-based farmer being the cornerstone of a prosperous rural society. It became a guiding principle of Victoria’s land settlement schemes.

To people from Great Britain – where every inch of land had been owned and traded for centuries – it must have seemed incredible that settlers in the new colonies of Australia could simply trek into the bush, mark out a large parcel of land and claim ownership without reference to anyone else.

The British Government, which claimed all land in Australia as terra nullius, stepped in and tried several different ways to regulate the system of private land ownership.

Not long after John Batman sailed up the Yarra River in 1835 to establish Melbourne, the squatters began arriving in Victoria, mostly from Van Diemen’s Land and NSW to illegally claim large areas of grazing land. The Henty Brothers had been squatting on Crown land at Portland from 1834.

In other examples, the Colonial government in Sydney either sponsored or sanctioned privately funded expeditions to search for new grazing lands and in return granted generous concessions.

By the end of 1838, according to the Crown Lands Commissioner, there were 57 squatters in the Port Phillip District.

“Squatters” carved out large estates on Crown Land they called runs and there was little the colonial government could do to stop them. They often objected to the term because it had originally been applied to ex-convicts who had illegally occupied small parcels on land. Instead, they saw themselves as “pastoralists”, an antipodean aristocracy living on large estates and homesteads built from the profits of the wool trade. But critics dismissed their upper-class pretensions by calling them the “squattocracy”.

In 1844, the Governor of New South Wales, George Gipps, required squatters to pay a yearly £10 licence fee and limited the size of each run. The license enabled the squatters to become legitimate pastoralists and to set up where they chose on Crown Land to graze cattle and sheep while waiting for it to be surveyed. The only limitation was that there would be three miles between stations.

Pastoralists then had a right to raise livestock on their “run” but licences could also be sold, and stations were constantly changing hands.

“Pre-emptive rights” were established in 1847 for squatters who had settled and made improvements to their land. They were permitted to purchase 640 acres (1 square mile) at the minimum upset price of £1 per acre. In this way the homestead, land and improvements could be secured before any surrounding land was made available to the public.

The squatters, who had good knowledge of their runs, claimed the best sections of land in a practice known as “peacocking”. The pre-emptive rights system was deeply flawed and widely abused.

By 1845, fewer than 240 wealthy squatters held all Victoria’s pastoral licences and proved a powerful political and economic force. They founded the exclusive Melbourne Club in 1838, which still exists today.

Prior to separation from NSW in 1851, there were five million sheep in the Port Philip District, but only 77,345 people. Wool was particularly profitable for these early pastoralists, and from the 1820s economic growth was based on the sale of fine wool to England which deeply shaped many Australian beliefs and identity.

After self-government was granted to Victoria in 1851, land continued to be administered under Imperial Acts and Orders-in-Council of the Governor of New South Wales. The first meeting of the Victorian Parliament wasn’t until November 1856.

At the time, the State’s forests and Crown Lands were still commonly regarded by the general public, and by most of their parliamentary representatives, as the inexhaustible “Wastelands of the Crown”, and ready for disposal via alienation and sale into freehold property for the purposes of agricultural settlement.

Influential and vocal segments of the community continually criticised the State Government for not exploiting and developing these remote and untamed lands.

But the Squattocracy and Land Barons were not about to cede their vast western district estates to settlers, nor their power in the Upper House of the Victorian Parliament. A pattern of conflict between the two Houses of Parliament continued for the next twenty years.

This growing resentment led to the formation in 1857 of the “Land Convention”, which began campaigning for reform. It was successful, and the Victorian Government introduced the Sale of Crown Lands Act (1860), also known as the Nicholson Act.

The Nicholson Act released 3 million acres of Crown Land for settlement and offered allotments between 80–640 acres of surveyed land at £1 per acre. Settlers could pay for half the allotment and lease the other half for up to seven years at one shilling per acre per year. Once the remaining balance was paid, they received a Crown Grant.

While there were some serious flaws in implementation of the Nicholson Act, this provision made an incredible difference to advancing land settlement. It also generated considerable and much-needed revenue into the colonial State Government coffers.

But the Nicholson Act provoked continuing confrontation with the squatters.

Access to water remained hotly contested, especially on the dry plains of northern Victoria. Pre-emptive rights typically secured access to reliable water in creeks or rivers. But in a visionary move, the Colonial Government established Crown Land frontages, which are narrow strips of public land along major rivers and streams. The law also forbade control of dual water frontages to prevent pastoralists from strategically monopolising all the permanent waterways for their own private use. A practice that could unfairly lock up the water resources and thereby excluding vast tracts of adjoining agricultural land from other settlers.

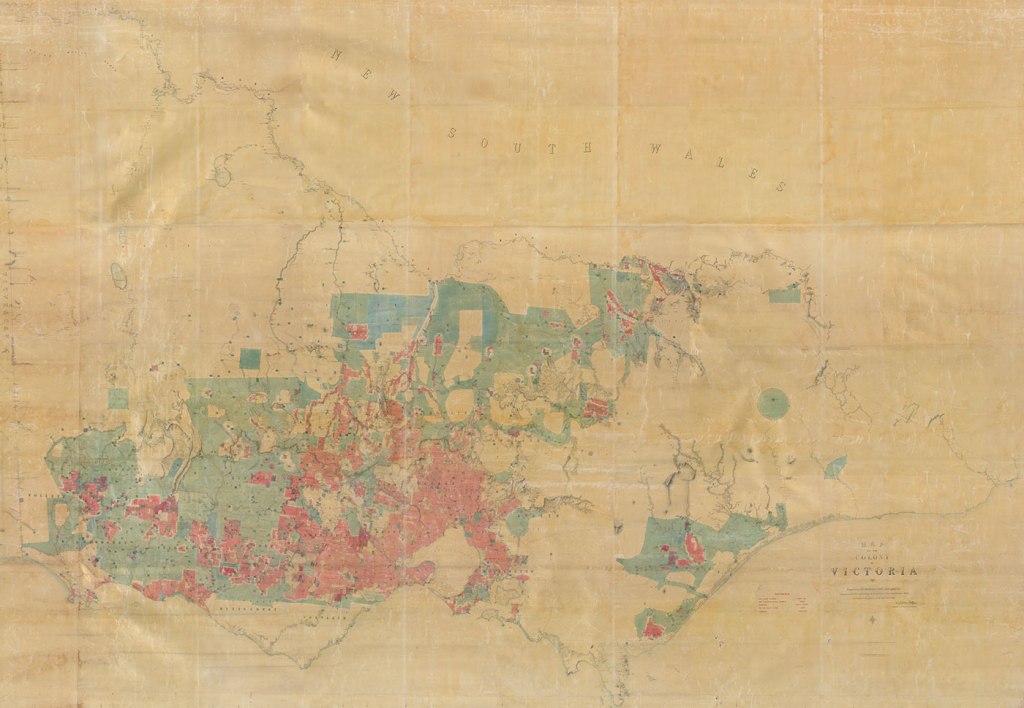

European settlement quickened with the passing of the Sale and Occupation of Crown Lands Act (1862), which was known as the Duffy Act, and attempted to resolve the conflict between squatters, gold seekers and small-scale farmers. The Duffy Act and subsequent amendments under the Grant Act (1865) released a further 10 million acres. The Act was accompanied by “the big map” which was one of the largest maps ever made in Australia, measuring 15 feet by 20 feet.

The term “Cocky” arose around 1870 to describe struggling farmers and settlers trying to scratch a living from the soil like cockatoos. But the nickname grew to reflect a sense of pride and self-assuredness, highlighting their resilience and connection to the land.

Importantly, a Section 41 of the Amending Land Act (1865), or Grant Act, allowed the Governor-in-Council to “…reserve from sale any Crown Lands which were required for the growth and preservation of timber…”. The Governor also approved the granting, cancellation, revocation, and transfer of licenses. The Act made provisions for bridges and level crossings.

The later Land Act (1869) allowed for the selection of up to 320 acres, including unsurveyed land, via the process of licensing, leasing and grants. A licence could be issued for three years at an annual rent of 2 shillings per acre, paid half yearly in advance. After that, the selector could apply for a seven-year lease at the same rent. After paying a total of £1 (20 shillings) per acre, the selector could apply for a Crown Grant, that is, land held by the Crown could be granted to the selector as the new owner.

Licence holders were also specifically barred from mining their selections under Section 20.

The Land Act (1884) was a revision of the earlier Land Act (1869), but under Sections 32 and 42 selectors had to pay the same price for land, £1 per acre, regardless of its quality.

This Act also allowed a grazing lease of up to 1,000 acres at an annual rent between 2d and 4d per acre, but the land could not be purchased and would revert to the Crown by 29 December 1898.

The 1884 Act also required selectors to make improvements, but those with poor-quality land could not make enough income to pay for the improvements.

For example, lessees of grazing areas were required under Section 32 to destroy all vermin within three years, enclose the land with fencing within three years and not remove timber except for use on the selection.

While licensees of agricultural selections under section 42 were required to destroy all vermin within two years, fence the land within six years, cultivate at least 1 acre in 10 during the licence period, occupy the land for at least five years and make improvements to the value of £1 per acre within six years. If these conditions were met, they could apply for a lease or Crown grant.

Needless to say, there was a lot of grumbling from cockies about the onerous provision of the 1884 Land Act. In 1898, the Commissioner for Crown Lands and Survey, Sir Robert Best, introduced fairer legislation to enable closer settlement and a new concept of land classification.

Settlers paid £1 per acre for half of an allotment but were required to make “improvements” regardless of its quality. They leased the other half for up to seven years at one shilling per acre per year and could pay off the balance at any time to receive a Crown Grant, which gave them ownership of the land.

However, Victoria was emerging from a financial depression in the 1890s associated with a post-goldrush hangover. It was also in the midst of the serious Federation Drought.

The Best Land Act (1898) also included a concession for existing agricultural leaseholders who were not able to pay arrears of rent.

The clearing of forests and timber by the early pastoralists for their sheep and cattle was intensified by the hopeful men who aimed to grow crops on their selections particularly from the 1860s onwards.

The latter tackled the more thickly forested areas which the squatters had avoided, such as the Otways and the great forests of South Gippsland.

The big trees were ringbarked in spring when the sap had risen. With a sharp axe the selector took off a one-foot strip of bark all around the tree and to make sure of killing large stems, chopped into the sap wood.

Although the tree remained standing, it soon lost its branches. This was a cheap way of “improving” the land as required by the selection acts. A competent axeman could kill three or four acres of trees a day.

The forested areas were frequently cleared of trees by fire which, more often than not, was not restricted to the landowner’s property but allowed to spread to adjoining forests.

The settlers were also permitted to obtain timber for their own use free of charge and this concession did little to instil a forest conscience in the community. A culture of forest destruction developed, almost without thought of the consequences.

During the 1800s, the State’s forests were controlled by the powerful Lands Department whose primary function was to survey, map and sell land for settlement.

Between 1849 and 1871 Victoria was divided into 37 counties and nearly 2914 parishes. These parishes were progressively surveyed by the Lands Department into allotments. This in turn allowed the colonial government to record the sale and transfer of land from the crown to selectors.

The Torrens Title system was introduced in Victoria in 1862 which provided a single record, or “Certificate of Title”, as conclusive evidence of land ownership. It gave confidence to land buyers.

However, there were still many serious allegations of coercion, and even corruption, within the corridors of power including the Lands Department, by those who sought to profit handsomely from the release and sale of Crown Land.

There was also evidence of “land banking” and “dummy bidding” whereby shady and wealthy speculators deceptively obtained land without actually occupying it, with the view to future sales and profits.

Furthermore, the colonial government viewed forests and wood as something that should be available for next-to-nothing for the large number of people battling to make a subsistence living from the earth. The government exerted only the lightest of controls in the form of annual licences to obtain timber for a modest sum, with no restrictions on species, sizes or quantity. Vast quantities of timber were felled by squatters and selectors and wasted.

While timber cutting for the mines during the goldrush had huge impact on the State’s forests, they were often left to regenerate naturally. Whereas clearing for agriculture was the primary cause of permanent forest removal.

By 1878, about 40% of the Colony had been alienated which coincided with its first surplus of food.

Not surprisingly, the Colonial Government had little appetite for changing the status-quo and introducing restrictive forest legislation.

However, the era of land alienation basically came to an abrupt end around 1925, with only minor acreages after that. Foresters and the newly formed Forests Commission played an important part in that massive change by pushing back against the Lands Department and calls for more land to be released.

The other key forces were a rising “forest conscience” within the community, and the political pressure of the big gold mining companies and the parliamentarians representing mining town electorates. They were seeing a timber drought firsthand with shortages of structural timber for pit props and firewood for boilers to run mining machinery. Shortages due in large part to deforestation in central Victoria caused by mining with no reforestation or planting.