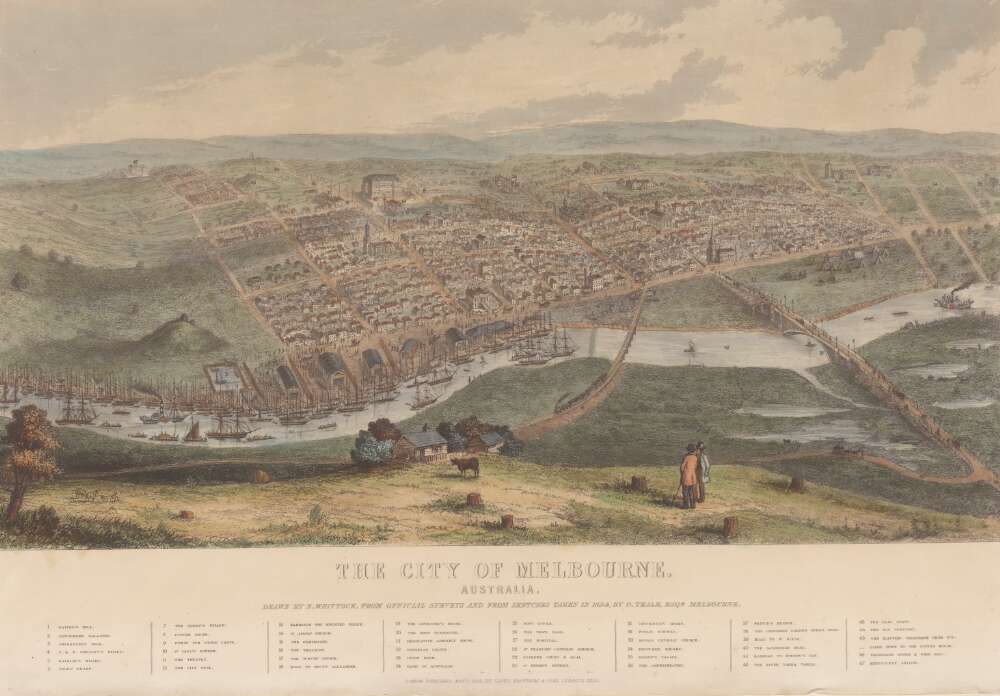

The Marvellous Melbourne we enjoy today began to take shape in 1854 and was paying for it in gold. They were heady times.

The MCG, Flinders Street Railway Station, Port Melbourne’s Station Pier, the University of Melbourne, both St Paul’s and St Patrick’s Cathedrals, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Customs House on the Yarra, while the Melbourne Museum and the State Library shared a site in Swanston Street. All of these and many more venerated public landmarks got their modest start in 1854.

The first edition of the Melbourne Age was also printed on 17 October 1854.

Melbourne’s own “Crystal Palace” was constructed of glass and wood in 1854 on the corner of William and La Trobe streets (now the site of the Royal Mint). It boasted 23,000 square feet of floor space and was built in just 70 days. The first of its type in Australia, it was designed to show off the gold-rich colony.

Australia’s first steam-powered city train, operated by the Hobsons Bay Railway Company, choofed on its first short journey on June 12, 1854, a full year before Sydney had any form of railway.

The thirsty citizens of Melbourne received their first public water supply in 1854, when a 150,000-gallon tank was built in East Melbourne, initially storing water raised by a steam pump from the Yarra River before the Yan Yean Reservoir came on stream three years later.

The goldrush lured thousands of hopefuls from around the world: Americans fresh from their own rush in California, arrived alongside Germans, Scandinavians, South Africans, Brits and Chinese among others.

Australian history was being made in other ways on the goldfields that were feeding Melbourne’s enormous wealth. And before 1854 was done, out on the Ballarat diggings, a ragtag gathering of miners fed-up with unjust treatment from the colonial authorities made the Eureka Stockade and the Eureka flag hopelessly romantic symbols of rebellion within the Australian story.

The explosion in immigration and the consequent demand for imported goods, presented Victoria’s administrators with their own bottomless money pit.

In addition to the hated mining licences, duties were levied on all imported luxuries brought into the suddenly wealthy colony, while a tax was levied on the export of gold. Customs revenue in 1850, immediately before the goldrush, was only £84,000, but by 1854 customs officers collected the same amount in a month.

To avoid the tax, ships carrying Chinese passengers dropped them off in Sydney, Port Adelaide and Robe in South Australia – requiring them to traipse many hundreds of kilometres on foot to the goldfields.

When the huge number of gold-seeking immigrants, at first housed in tents and crowded lodgings, finally turned their attention to more permanent accommodation, housebuilding leapt to a new level of activity with a 50% increase in the first few years of the 1860s. Steam powered sawmills together with the mass production of nails, and access to corrugated iron (rather than English thatch which was very fire prone), enabled thousands of new timber houses to be built. This added considerably to the pressure on the native forests.

But the goldrush and Melbourne boom petered out by 1880s and was inevitably followed by a financial crash in 1891, which combined with the Federation Drought from 1895 to 1902, depressed economic conditions for a decade or more.

But in February 1854, an Act to Restrain the Careless Use of Fire was passed.

Source: Tony Wright – Melbourne Age