By Rob Youl – Reproduced from Victorian State Foresters Association (VSFA) Newsletter #38 April 1977.

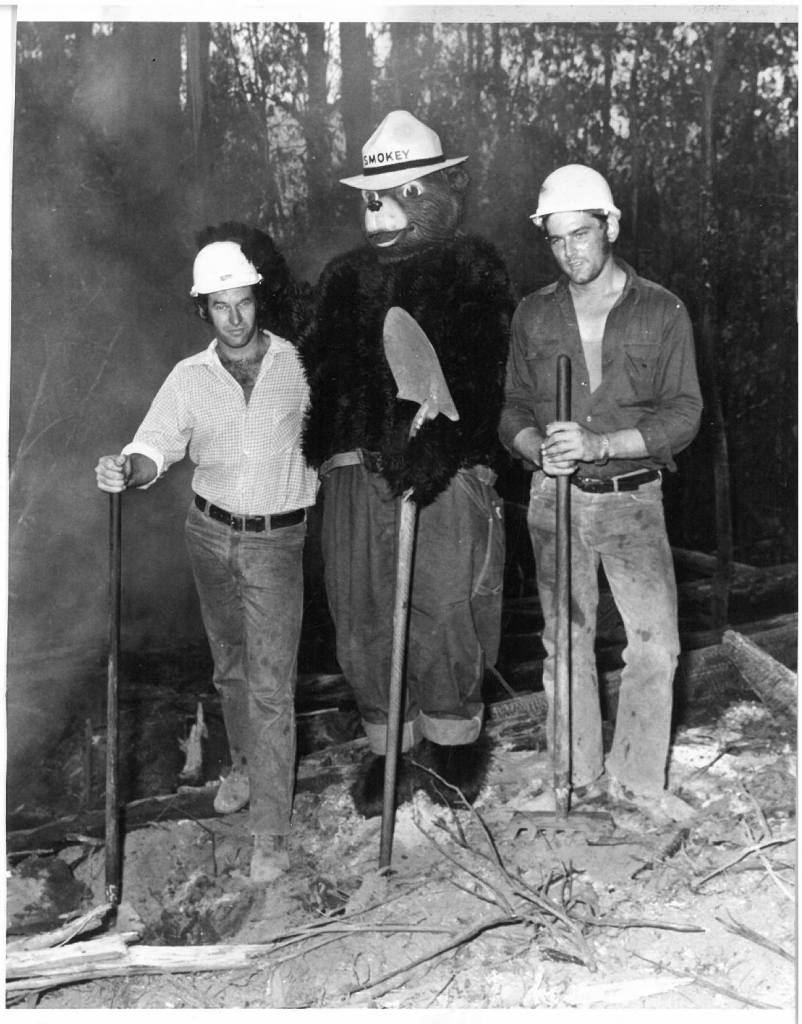

Almost 50 years later, the author apologises for his sexism, insensitivity and excess testosterone. Furthermore, he trusts his readers will discard their disgust and accept this as the zeitgeist[1] of the 1970s. But more embarrassingly, I ask myself now, why didn’t I brandish a rakehoe in the photo?

I’d led a drab and conservative life until that fateful day.

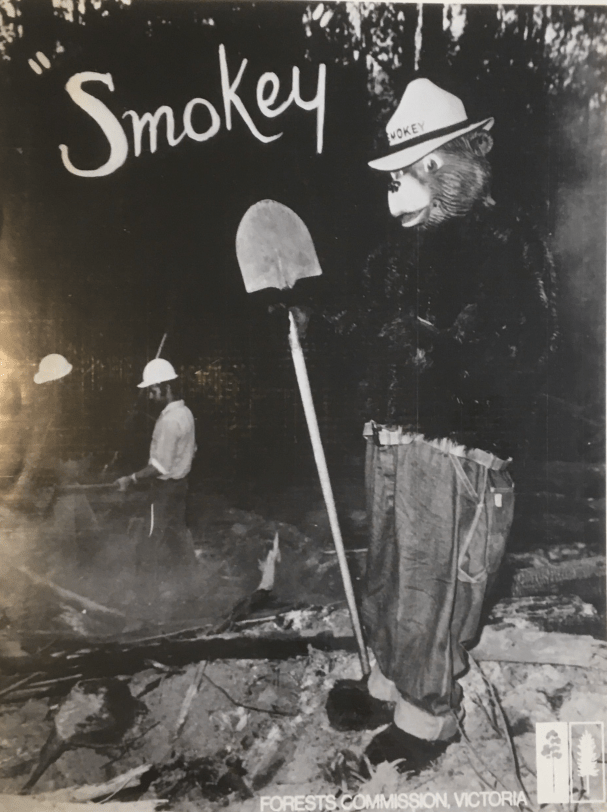

The Public Relations Officer called me in. The US Consulate just rang offering us Smokey Bear. We want to put him in Moomba. My reply probably reflected my interest in the protection of our national culture and my knowledge, as a gardener, that horse manure made excellent compost. But we need a human body to drape the suit around. How about you? I agreed. I knew that a few others would be silly enough to ley themselves in for such a task and I thought that seeing half a million Victorians through Smokey’s eyes would be interesting (for I presumed that he had ocular orifices).

I met the bloke from the Consulate, and he showed me the United States Forest Service Information. I suddenly realised that the whole effort had to be taken more seriously than I usually approach things. One suddenly had responsibility on a nation-to-nation scale. I therefore resolved to stay sober and decorous, to never wander around with my Smokey head under my arm and to always ensure that my jeans were clean. It was intriguing to see State Department cables from Washington describing the famous bear’s visit – doubtless quite a frivolous change from the usual cryptic messages about shipments of hamburger beef and sales of F-111s.

The first appearance was at Tullamarine. The media would meet Smokey, but first they had to see Bobby Vee, ageing US rock star of the Brylcream days of yore, who’d arrived on the same plane as I ostensibly had. I’d loved “Rubber Ball”, “Be True to Your School” and “Take Good Care of my Baybee”, but, waiting in the wings under wraps, dressed up for the first time and ready to go myself, I wasn’t able to ask him for his autograph.

Smokey was ushered in. Arc lights glared. The sweat flowed as if through opened floodgates; the RH rose. Athol and Big Frank did the talking – Smokey is advised to stay mute. The media jocks took photos of him leaving the Pan Am jumbo with the hostesses. These young, and not so young, ladies were quite affectionate. As I hold them before the camera they speculated on my gender, and I found the massive size of my paw convenient camouflage for carnality until i was reminded by my shrewd mentor from the Consulate, “Now, now, Smokey. Decorum!”

Walking about the terminal I realised the anonymity of the suit prevented me from being embarrassed. It was also excellent in that it allowed uninhibited perving.

Outside the terminal Athol., looking handsome in his FCV uniform shirt, ably parried the probing questions of the splendid young TV interviewers, even a hard one about Blinky Bill. A couple of kids spotted me then and came running over, and I immediately realised Smokey’s greatest strength and, in fact, his raison d’etre. The children were excited, but pleasant and friendly. They recognised Smokey from television cartoons they’d seen. We were to drive off triumphantly in MZF*000 led by police motorbikes; I climbed into the limousine but was jammed in a foetal position because my unfamiliar hat added inches to my height.

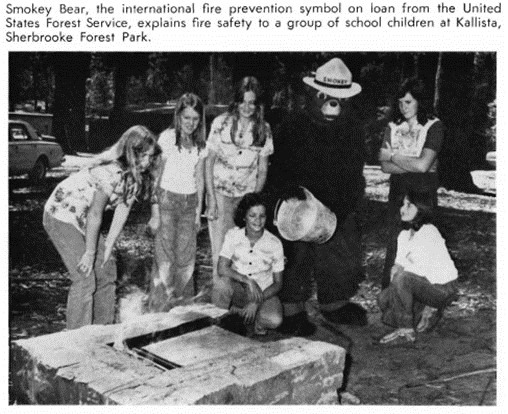

The next engagement was days later at a Mulgrave kindergarten. The kids were a delight although some of the photos taken showed Smokey looking like a child molester. Then we drove off to Sherbrooke. A group of pensioners on a coach trip enjoyed the unexpected anthropomorphic spectacle and the Kallista school marched down to hear John Lloyd and Bill Clifford talk about fire prevention. The Sun photographer took pictures of Smokey holding two kids on his shoulders. The pose had to be held for a couple of ultimately agonising minutes. I was mobbed by the kids, and in the melee, lost a bear paw. Thank God it was quickly found and tied into place. I could hear the kids debating below me. Despite the evidence of the briefly glimpsed boot underneath the paw, most of the children refused to believe that Smokey was human and not ursine[2].

The girls from St. Monica’s Convent, Footscray, wanted autographs and I discovered the thrill of being a celebrity. For 10 minutes I was Dennis Lillee. “From Smokey to Debbie and Wayne”. “From Smokey to Pia and Shane”.

Healesville was next with a Rod Incoll pyrotechnical master touch. We drove in, bear on tailgate, with Dave Osborn holding aloft a yellow smoke bomb. Rod told the 500 children I’d sign autographs and suddenly Smokey was surrounded by clutching, clawing, tugging, grabbing, pulling, pushing, probing, thrusting, jostling, bustling organisms. I recalled Hitchcock’s film “The Birds’ and all that I’d ever read about mass hysteria. One kid was heard to say “Let’s see whose Dad’s inside! There was only one thing to do. Military training provided the instinctive reaction. “On the command Abort Mission, Abort Mission! OK, Abort Mission”. We were away.

Then it was off to Marysville, and Smokey’s greatest thrill in a brief career as a multi-media personality. The energetic and capable young headmaster had the kids outside the school with placards and ready to cheer. Smokey was escorted through the gate to a green-painted, bracken-garlanded throne made from beer boxes and then given presents – the school’s entire output of arts and crafts for that day, in fact. The children took Smokey to a camp they’d set up with tents and fire pit and confidently told him why they’d taken the precautions they had. One lad came forth with a brown paper parcel which had a reassuring cold, metallic, cylindrical feel, a present from the teachers. Smokey was escorted back out the gate and was very moved by the warm and polite juvenile adieux like “Come back again, Smokey!” repeated by so many.

The Moomba sun rose, and we assembled at Carlton. I felt like Clark Kent as I changed in a basement car park. Added fuel to my fetishes was provided by the rubber urine bag (the suit itself has no drain holes) with AD/DC, S&M, B&D undertones and overtones, which I lashed to my thigh. From the float I recognised and amazed an old friend I hadn’t seen for years. I don’t think he’s sure even now who he was talking to.

The parade began. Immediately behind was the delightful Ms Italian Community. (Trevor Brown had been doing his bit to make Australia a more assimilated and happy nation by keeping her company and calming her nerves). I soon discovered that I had little time to leer or even look.

I discovered also the Queen has a very difficult job. Waving makes you tired. The cheering was intense as the masses of humanity, orchestrated by the enthusiastic Tony Manderson, roared approval of our float. I leapt around trying to acknowledge everyone, but even at one km/hr that was difficult. Ask Jim Stirling, intrepid photographer. He found taking shots of the procession from all angles hard going at that speed too. At one point our smoke generator caught fire, but quick-thinking Kester Baines solved that problem. One noticed the police were rarely wreathed in smiles, but that the dignitaries outside the Town Hall were as extroverted in their behaviour as everyone else who formed the crowd.

The parade slowed down in the gardens, but the kids still shouted and cheered.

A crisis developed. The suit had to be in Sydney that night for a tourist promotion. The plane left Tulla in about half an hour. A quick strip behind the float’s grove of brush box trees and a police escort got the suit dispatched.

One reverted to life as a human. When I waved no-one cheered. When I waved no-one responded. When I held my arm out in front of me i didn’t see a furry paw, but distinctly Caucasian hand. I was Rob Youl again. The experience gave me an insight into the life of a professional actor and how the characters one plays could dominate your own character. I thought that I could see why George Reeves, the former Superman, had killed himself.

Impressions from the parade were that there’s still a lot of kids in Victoria, even if population growth is close to zero, that this country still produces very attractive women, that our population is now exceedingly heterogeneous, and that Melbournians aren’t entirely staid and stolid.

Quote of the week was the statement by Alan Threader, “You should be in a rat’s suit, not a bear’s!

A couple of late performances at Creswick (thanks a million, Tom [Morrison]), Yooralla, Toorak and Heathcote and we packed Smokey into his crate. It must be bloody cramped in there for him. Back he’ll go to the USA.

And you might criticise our use of an American Madison Avenue folk figure. Keith Dunstan did (The Sun, 21 Mar 77). Well, we never said that Smokey was anything else than that. Like my other visiting fireman does, he came for a look around, and he gave pleasure to many children and plenty of adults too. He also made some of those citizens, of all ages, think about fire prevention. To criticise Smokey specifically is to ignore the overall assault on our culture, and on the remnants of our national identity. In a global village, in a world where trade is free, there are thousands of international influences we cannot avoid. We can’t avoid Sony calculators, Abba, London and Liverpool slang, sweet and sour pork, Danish blue movies, Starsky and Hutch, and Peugeot bikes, any more than we could avoid computers, or the environmental revolution or the permissive society.

[1] zeitgeist – the defining spirit or mood of a particular period of history as shown by the ideas and beliefs of the time.

[2] Ursine – relating to or resembling bears.