In mid-1968, Sir William “Blackjack” McDonald, a pastoralist from western Victoria and the Minister for Lands, Soldier Settlement and Conservation, controversially announced a new rural settlement scheme which involved clearing of remnant mallee woodlands and then selling Crown Land in the Little Desert. Some two hundred thousand acres was slated for agricultural subdivision.

The immediate outcry over the Little Desert proposal galvanised public opinion and threatened to become a major political issue for the Liberal government led by Sir Henry Bolte.

For the first time, the many disparate and divided conservation groups joined forces into a peak body known as the Conservation Council of Victoria.

An unlikely alliance of farmers, agricultural experts, economists, academics, suburban activists, scientists and conservationists banded together to stop McDonald’s scheme. The plan was even opposed by some Liberal politicians, including a young Bill Borthwick, who later replaced McDonald as minister.

For more than 100 years there had been occasional bitter disputes between foresters and the Lands Department over the clearing of forests and selling of public land. The new Conservation Council of Victoria enjoyed the support and benefited from the considerable political nous of some very influential forestry bureaucrats. Those quietly offering valuable contacts, insights and advice from the sidelines included the recently retired Chairman of the FCV, Alf Lawrence, the local FCV District Forester and noted ornithologist on the edge of the Little Desert at Wail, Bill Middleton, together with Dr. Peter Attiwill, a respected forestry lecturer from the University of Melbourne.

Leading Wimmera naturalist and National Park Ranger at Kiata, Keith Hateley, who the father of notable forester and gifted VSF lecturer, Ron Hateley, was also outspoken against McDonald’s plan.

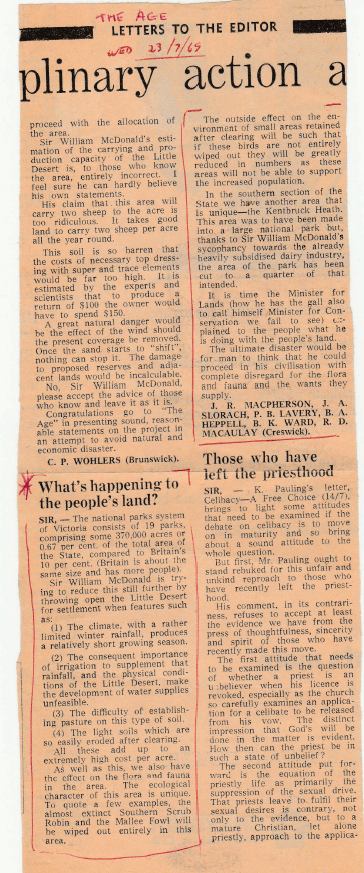

In July 1969, several students at the Victorian School of Forestry also joined the protests with a jointly signed letter to The Age.

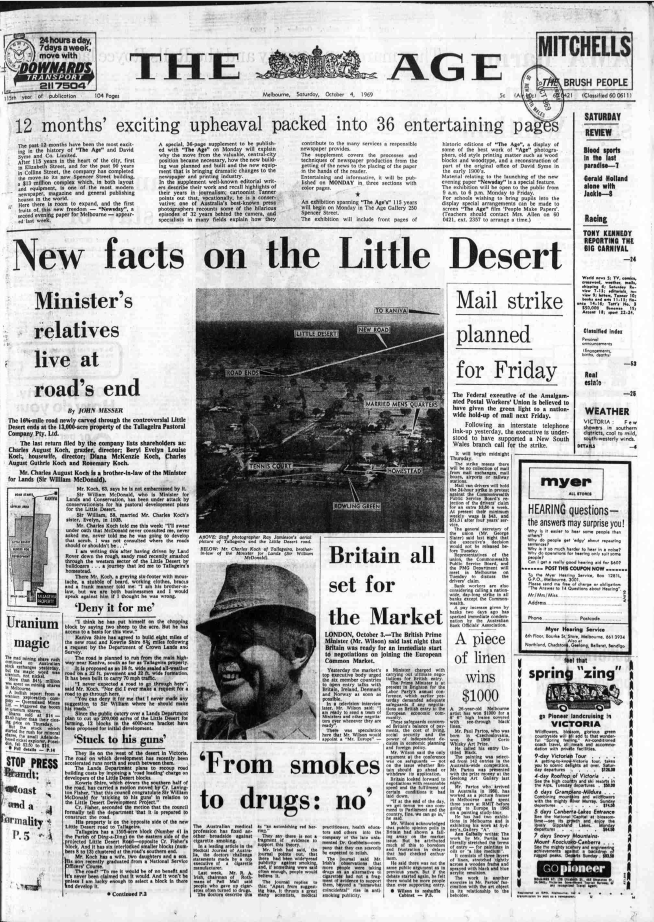

The Age Newspaper was fiercely critical and ran months of reports and editorials opposing the proposal.

Controversially, on 4 October 1969, a front-page story revealed a 16-mile road to be built through the desert would end at the property of Blackjack McDonald’s brother-in-law, Charles Koch. McDonald denied any wrongdoing or conflict of interest and demanded an apology from The Age for what he deemed “the tactics of low-class spectacular journalism”. He remained defiant and indignant and later sued The Age for libel, but eventually settled the matter out of court.

By November 1969, Sir William, who had initially dug in for a fight, was forced to capitulate and scale back his bold scheme to just twelve sheep farms, while at the same time announcing the creation of a new 90,000-acre Little Desert National Park.

But on 4 December 1969, the Labor and Country parties combined in the Legislative Council to block the Bill and McDonald’s poorly conceived scheme was consigned to oblivion.

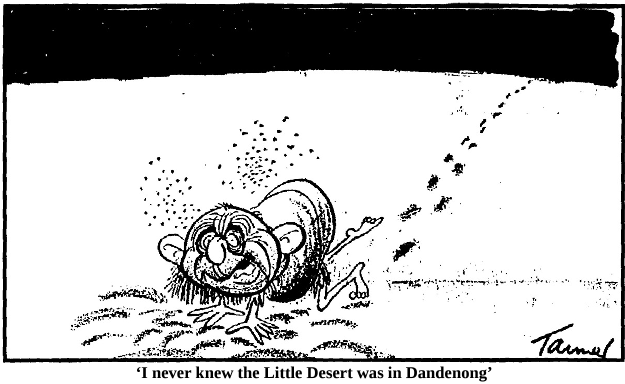

Furthermore, the surprise loss of the safe Liberal seat of Dandenong to Labor’s Alan Lind (the nephew of long serving politician for East Gippsland and former Minister for Forests Sir Albert Lind) on the 6 December 1969 byelection sounded alarm bells and forced the government’s hand.

The State Premier, Sir Henry Bolte, was at a loss over the unexpected public outrage and wanted to diffuse the newly emerging “greenie” disquiet. As the longest-serving Victorian premier in history, he was not about to end his reign with an inglorious electoral defeat over a bit of mallee scrub.

During the 1970 election campaign, the usually hard-nosed Bolte promised at a public meeting in Ararat to increase the size and number of national parks, establish an environmental protection agency and acquire large areas of the Dandenong Ranges for public use and to improve fire protection.

But there remained a widespread electoral backlash against the Bolte Government in the May 1970 elections when the Country Party directed preferences against the Liberal Party across the State. Bolte narrowly won the election, but McDonald ignominiously lost his safe Liberal seat of Dundas, after holding it for over 15 years.

The summation of these tumultuous political events in the late 1960s proved a watershed moment and are often considered to mark the beginning of widespread environmental awareness and activism in Victoria.

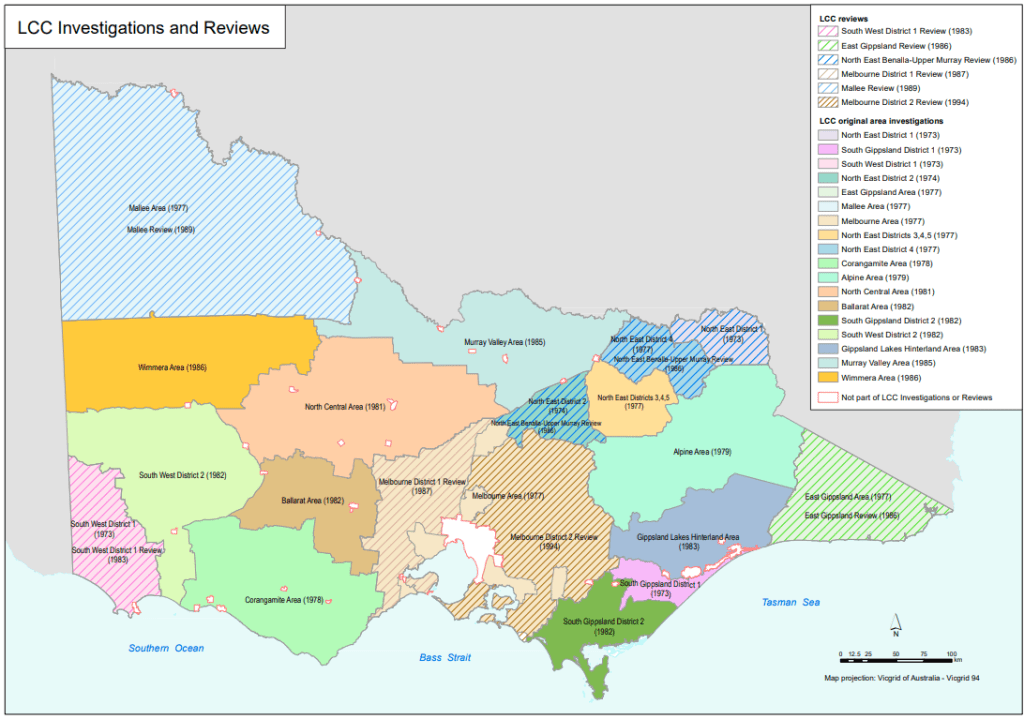

Ironically, McDonald’s failed Little Desert plan laid the foundations for the State Government to create the Land Conservation Council (LCC) later in 1971. Its main charter was to make recommendations to parliament on the balanced use of Victoria’s public land.

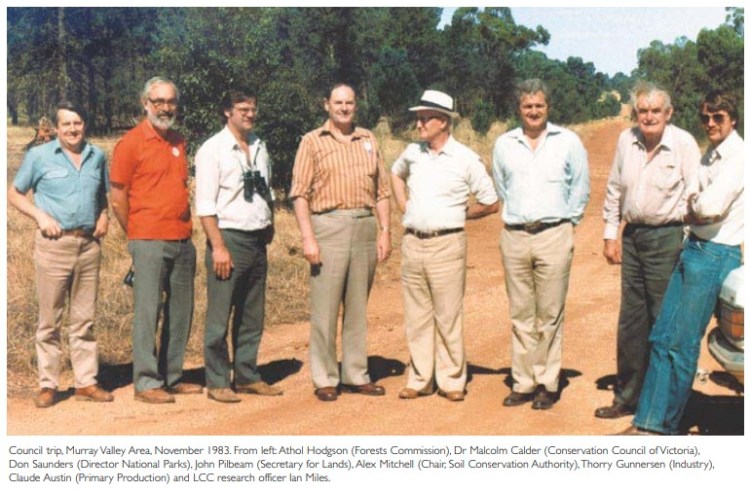

The LCC was chaired by the formidable and politically well-connected figure of Sam Dimmick, while the Forests Commission was represented by its Chairman, Dr Frank Moulds.

The Council was proposed as an impartial mechanism to assess public land use but there were criticisms of its early composition as a “closed shop”, dominated by permanent heads of government departments. But the LCC pioneered processes for community input and many FCV staff moved over to the new organisation. One of the first was the talented Roger Cowley who drafted the policy that led to the initial definitions of reserves.

In its early years, the LCC’s community members included Professor John Turner, head of the School of Botany at the University of Melbourne, and John Landy (later Governor of Victoria) who was an agricultural scientist working for ICI and was also well-known for his sporting achievements. Later Dr Malcolm Calder brought his considerable botanical expertise to the LCC’s deliberations.

When Bill Borthwick, Victoria’s newly minted Minister for Conservation, delivered his welcoming speech to the freshly formed council members he advised them to make their recommendations… “as if for a thousand years”… And with that, he left them to it…

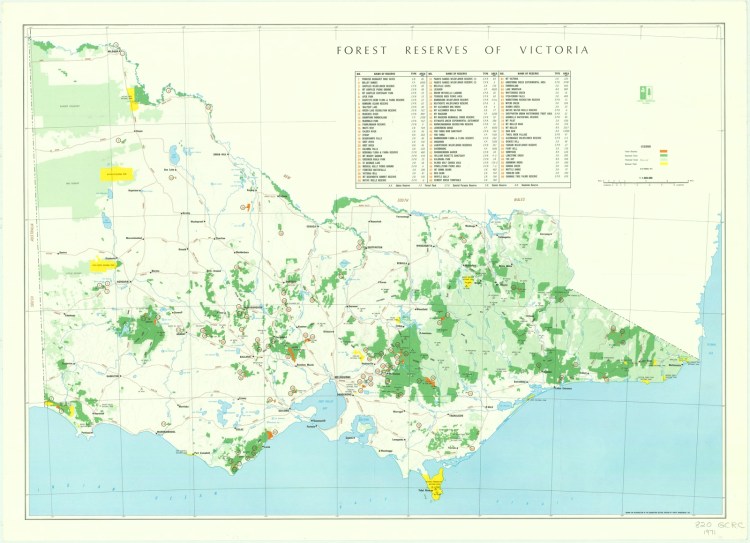

More than a decade earlier, in 1958, a major revision of the Forest Act included a new provision known as Section 50 which gave the Forests Commission powers to set aside State forests for special purposes such as recreation, conservation, landscape and so on.

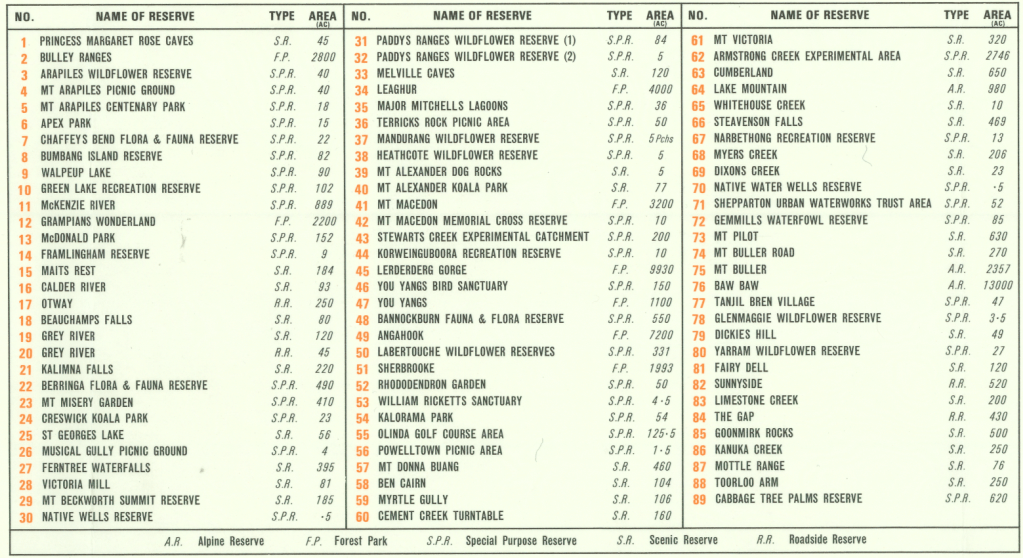

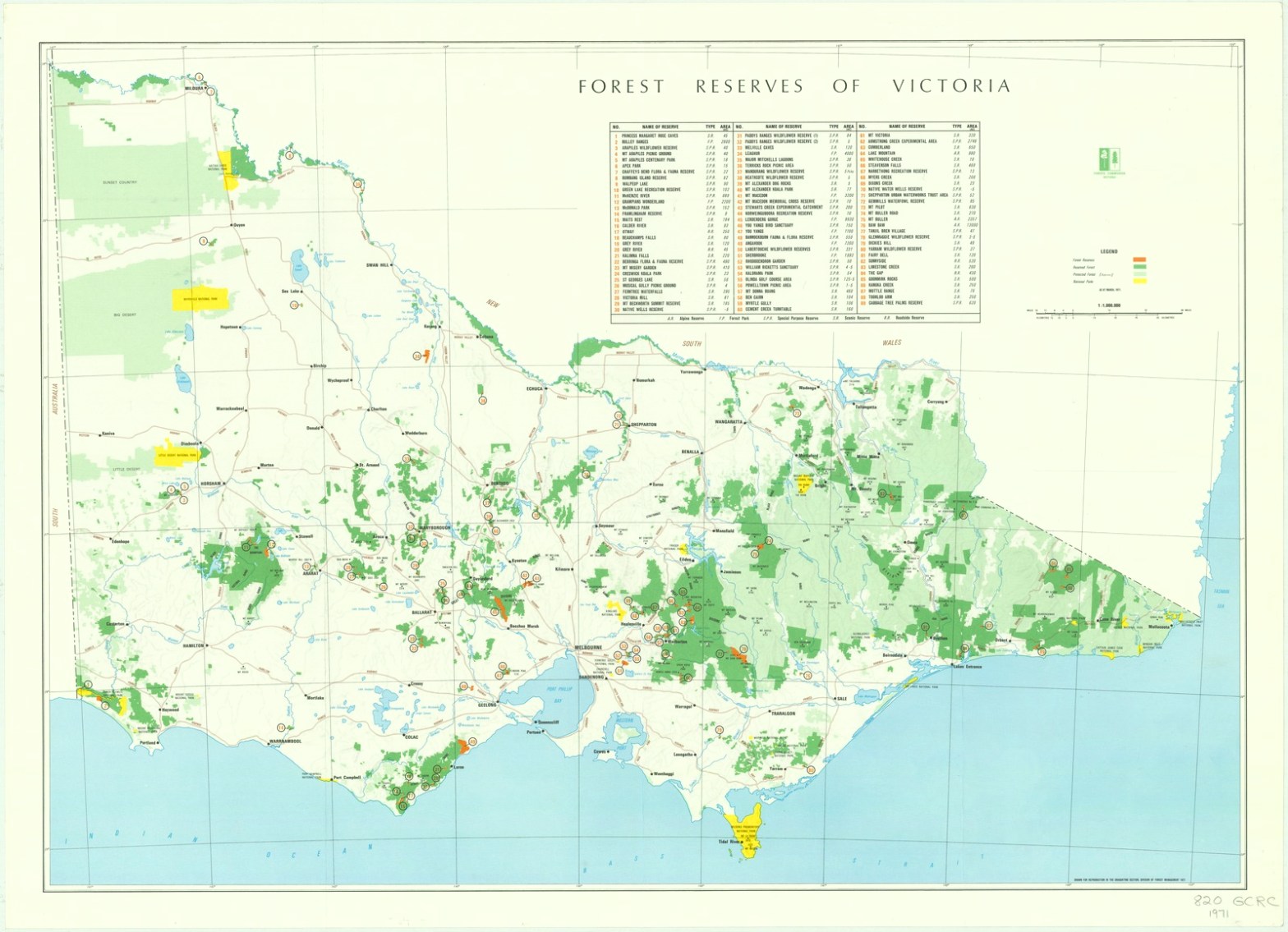

By the time of the formation of the LCC in 1971, the Commission had set aside some 88 Section 50 Reserves including Sherbrooke Forest, Grampians Wonderland Reserve, Mt Macedon, Angahook, and Mt Baw Baw.

In response to shifting community moods, the Commission, under new Chairman Dr Frank Moulds, also formed the Recreation Branch. By 1972, its responsibilities had been considerably broadened and it became known as the Forest Environment and Recreation Branch (FEAR). This new direction did not initially enjoy whole-hearted support throughout the organisation, but it was soon embraced, and other State forest agencies quickly adopted the idea. FEAR Branch was first headed by Athol Hodgson.

Meanwhile, the Commission continued to strongly advocate for multiple use of the State’s forests as its core policy. The idea aimed to use forests for more than one purpose and compliment the more formal conservation reserves such as national parks. The central objective of multiple use was to balance timber production and other forest products such as firewood, farm timbers, fence posts, poles, sleepers and honey. It also provided for active recreation, protection of landscape, historic places, as well as water and biodiversity conservation. Protection from fire remained an overarching theme.

The visionary and robust deliberations of the LCC ultimately led to a progressive expansion of Victoria’s magnificent National Parks and Reserves.

In 1956, when the first National Parks Legislation was enacted, only 13 Parks existed including the iconic Mt Buffalo and Wilsons Prom. But by 1975, when the first of the LCC’s recommendations were tabled in parliament, that number had increased to 26, totalling over 226,000 ha.

The LCC morphed into the Environment Conservation Council (ECC) in 1997 and then into the Victorian Environmental Assessment Council (VEAC) in 2001.

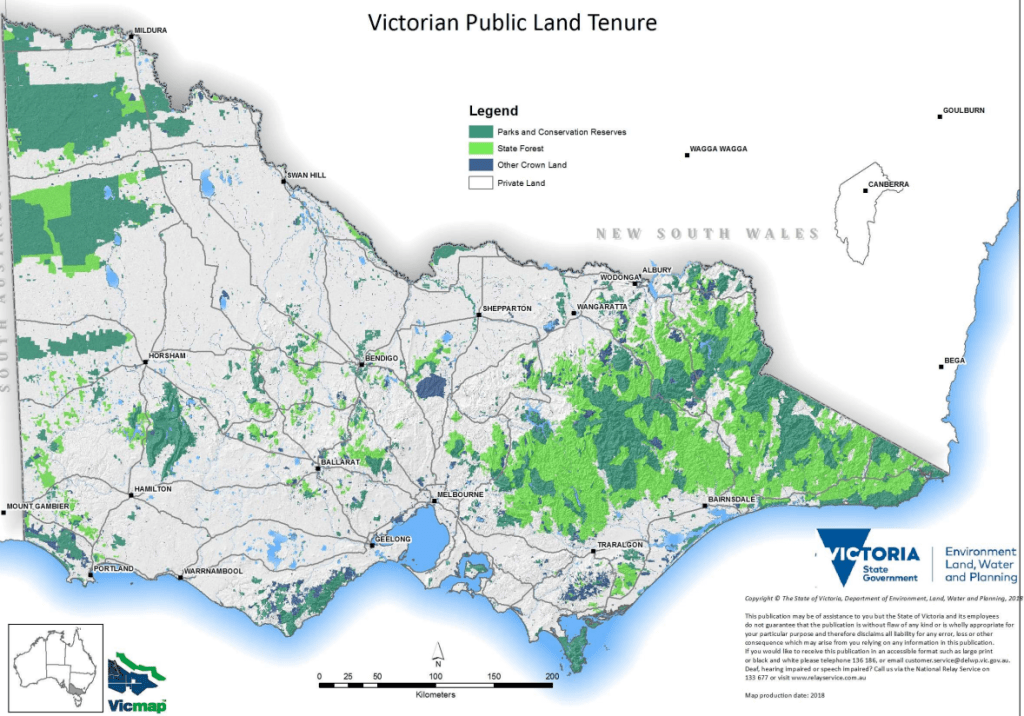

By 2024, a bit over half of Victoria’s public land estate of 7.1 million Ha was set aside as Parks and Conservation Reserves with the remainder as State forests.

New parks in western Victoria around the Wombat Forest have recently been added and some controversial parks in the Central Highlands are proposed and being vigorously debated.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1zt7JwloS6gpO78WUfckkl03gO_TGWh5Z/view