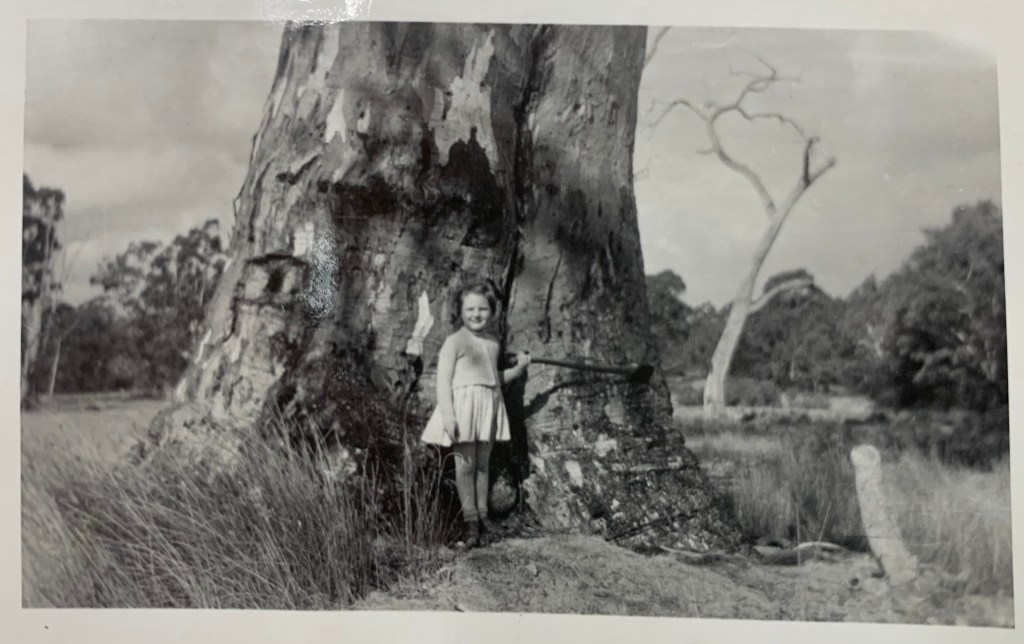

The magnificent Bilston Tree near Brimboal in far western Victoria was a big part of the local consciousness in the late 1950s.

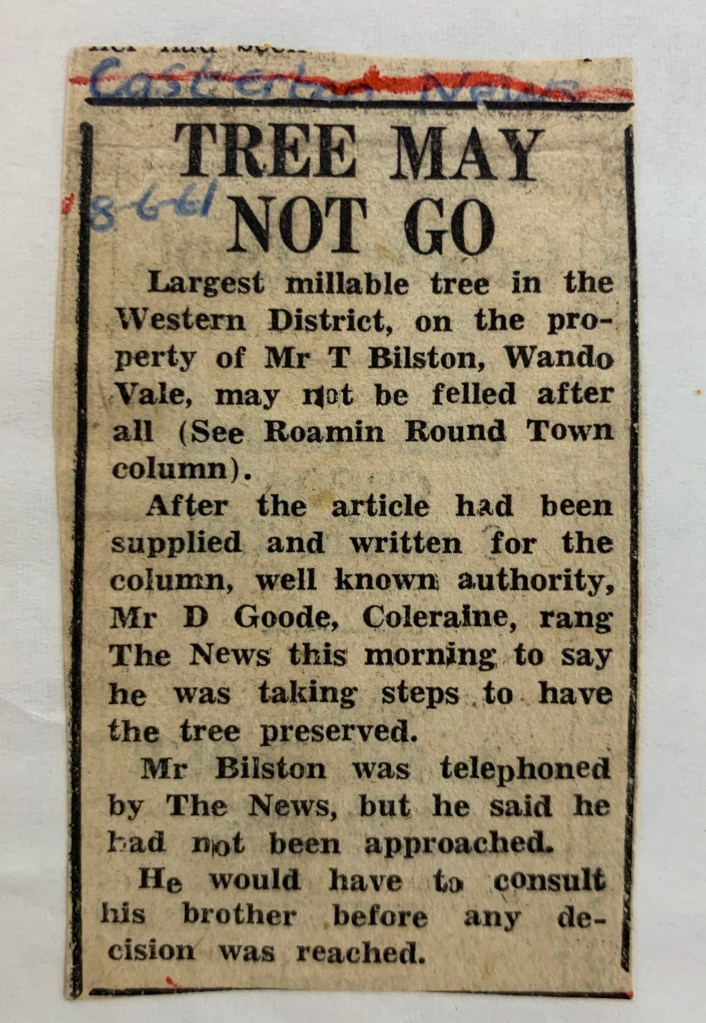

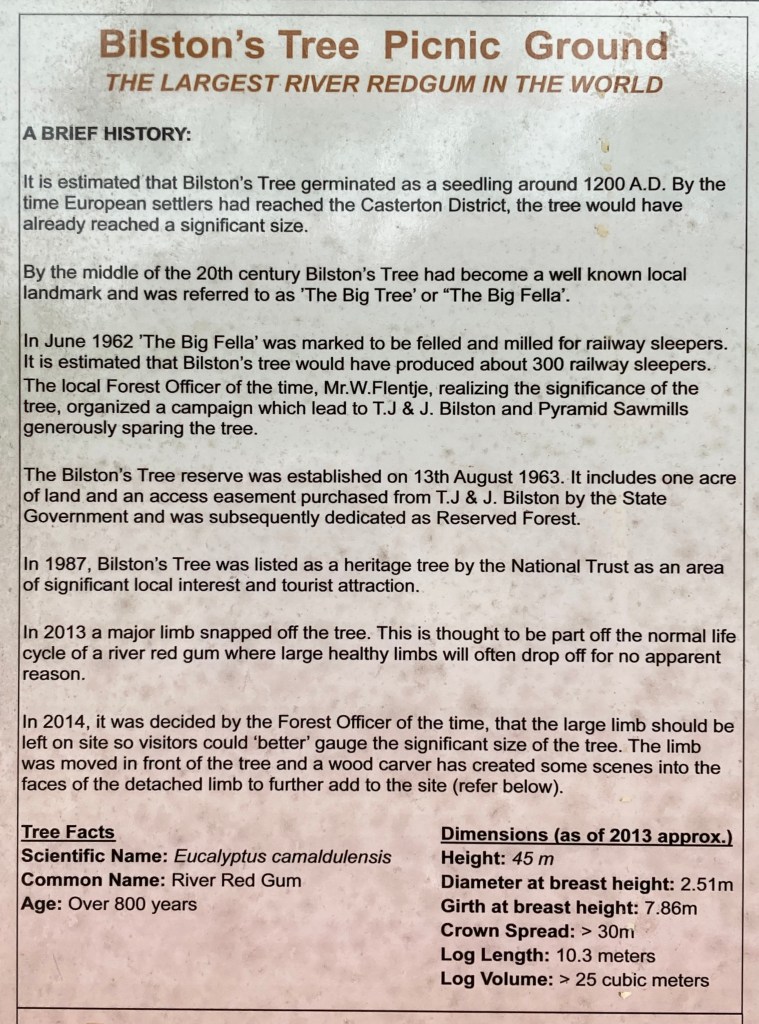

The massive river red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) was scheduled to felled for railway sleepers on 12 June 1961 but was saved by local community action led by Bill Flentje, the District Forester at Casterton.

Subsequent negotiations between the Forests Commission Victoria (FCV) with the landowners, Mr Thomas Henry Bilston and his brother Mr John Wheeler Bilston, as well as Mr Lance Thyear from Pyramid Sawmills, led to the acquisition of the tree by the FCV on 6 March 1962 for the sum of 70 pounds as compensation for the loss of timber.

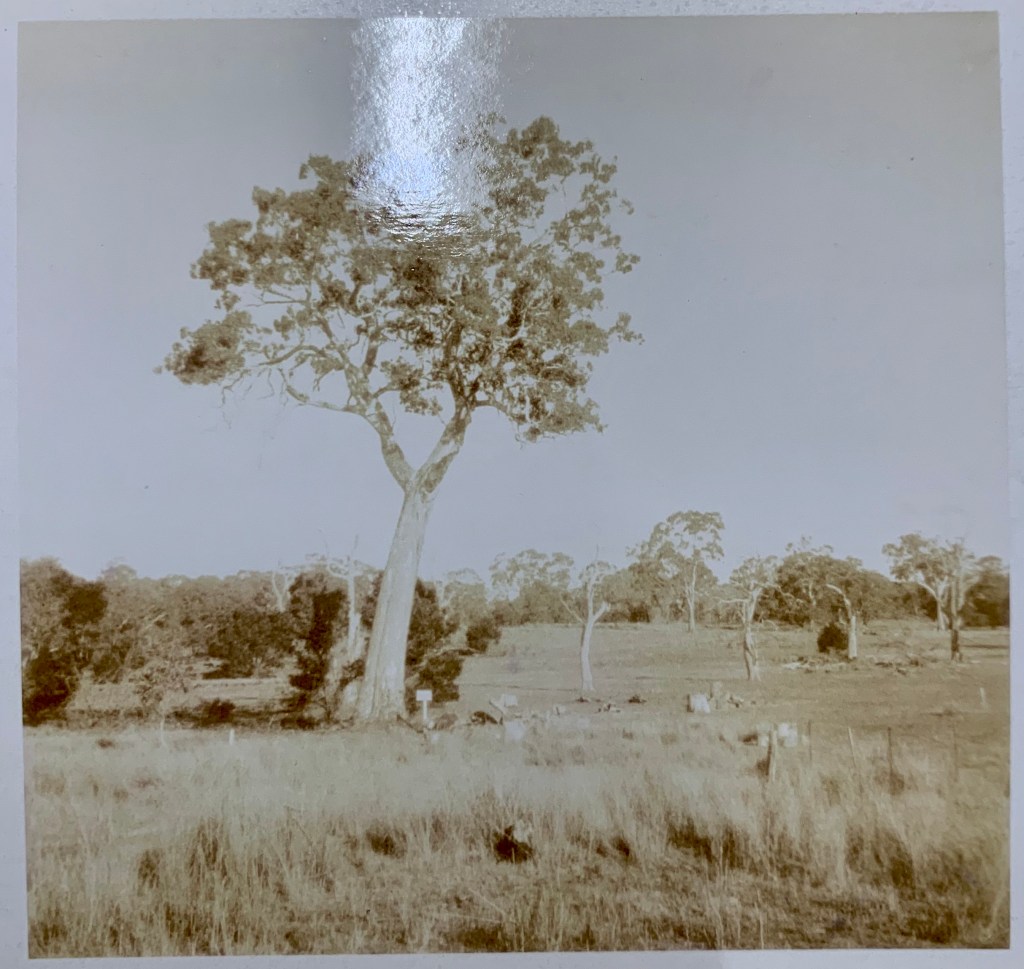

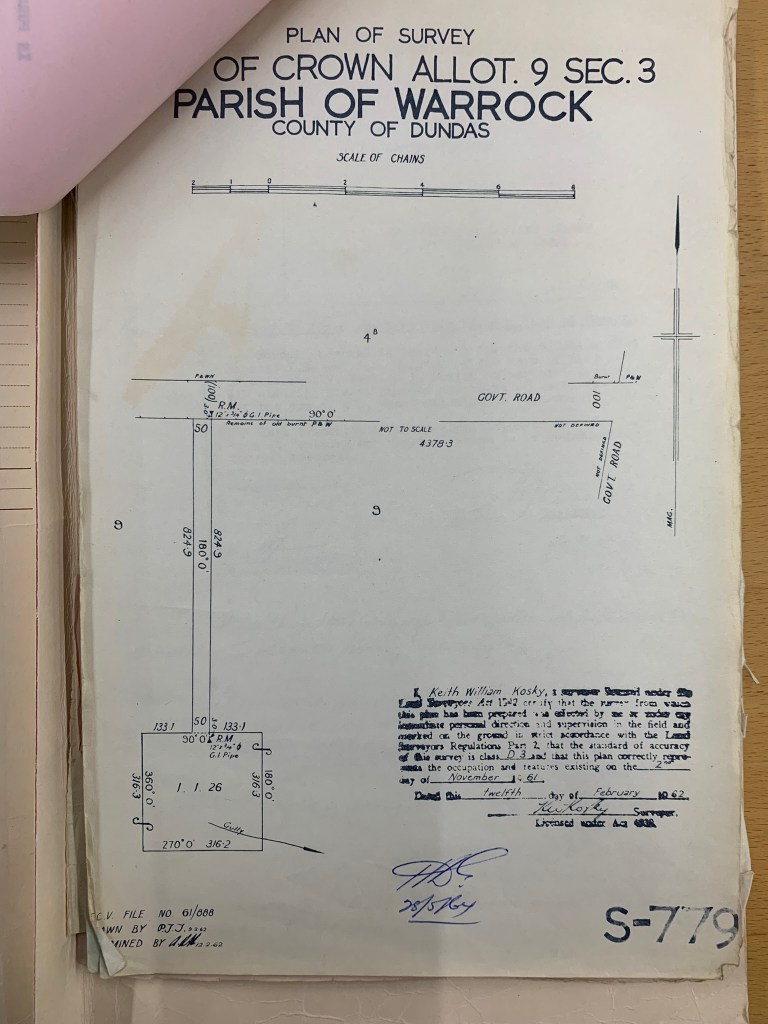

Significantly, the Bilston brothers also donated a small patch of land (1 acre, 1 rood, 26 perches) surrounding the tree, including a half-chain-wide right of carriageway.

The brothers had always wanted to see the tree preserved as a tribute to their grandfather who had been one of the district’s earliest pioneers. Thomas Bilston (Snr) had driven stock into the area in 1839, shortly after Major Mitchell’s historic expedition in 1836, and the Henty Brothers had established Portland’s first permanent settlement in 1834.

In the late 1950s, they had offered to gift the tree to the National Parks Authority (NPA) and contacted Dewar Wilson Goode from Coleraine, a prominent local pastoralist, conservationist and board member of the NPA, but he was not in a position to accept the generous proposal.

All the standing timber on three paddocks of the Bilston’s property was subsequently sold for a cash amount to Pyramid Sawmills at Casterton but the owner, Lance Thyer, could readily see the significance of the big tree to the local community and was instrumental in having it saved.

Lance wrote to the Minister for Forests, Mr Alexander John Fraser, in August 1961 to advise that he had willingly forfeited 10,000 super feet of timber that would have been cut from the Bilston Tree but, instead, had harvested an equivalent volume of unallocated timber from another paddock owned by the Bilstons.

A total of 70 pounds (which was roughly the equivalent of four times the basic weekly wage) was offered to the Bilstons by the State Government as compensation to offset the loss of revenue from the additional timber made available to Pyramid sawmills.

The donated land around the tree was then transferred to the Crown on 16 August 1963, with legal fees of 4 pounds and 4 shillings met by the FCV. The land was subsequently declared Reserved Forest on 28 May 1964.

At the time of purchase, the tree was thought to be about 400 years old – not 800 as is now more commonly claimed.

Its circumference was estimated (annoyingly, not measured with a tape) at between 27 and 29 feet (at shoulder height – 5 foot). The total height was also estimated at 135 feet.

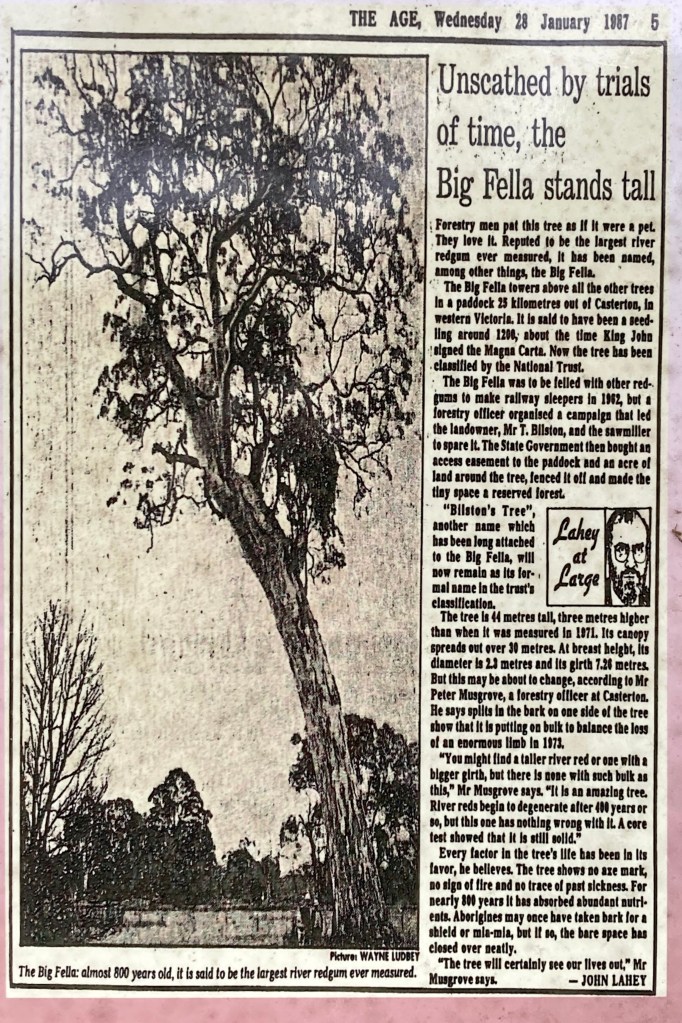

The massive specimen was once known as the “Big Fella”, but now more commonly as the Bilston Tree after the original landowners, is listed on both the National Trust and Victorian Heritage Registers.

A sign on the Casterton-Chetwynd Road makes the bold claim that the Bilston Tree is the world’s largest river red gum. Tourism websites and Google repeat the assertion.

But how do you best measure a river red gum ??? – is it height, girth, diameter, crown size, crown spread or log volume ???

The national register of big of trees, compiled by well-known botanist Dean Nicolle, uses a points-based system combining height, girth and crown spread to identify Australia’s largest river red gums.

The Bilston Tree, with 443 points, makes it onto the list, as does the well-known tree at Guildford near Castlemaine (562 points), but the biggest river red gum in Victoria is the “Morwell Tree” in the Grampians which accumulated a massive 700 points.

The Bilston Tree is not exceptionally tall either. A gun-barrel straight river red gum in the Barmah state forest named “Codes Pile”, after the Chairman of the Forests Commission, William James Code, was measured at 46.6 m. The Bilston Tree is also not of great girth, being only 812 cm measured at breast height (1.3 m) above the ground.

There are certainly lots of river red gums with more bulk (or biomass) but the unique thing about the Bilston Tree is its clear unbranched trunk, with very little taper, up some 40 feet (12 m).

Estimates in 1971 suggested that 9,100 super feet (HLV) or 21.5 m3 of timber could be sawn from the tree, which is enough for over 300 railway sleepers. This probably makes the Bilston Tree the largest “merchantable” river red gum.

The local Forest Overseer, Peter Musgrove, reported in 1987 “you might find a taller river red, or one with a bigger girth, but there is none with such bulk as this”.

River red gums are a bit like people. They shoot up in height in their early years. But, also a bit like people, river red gums then slowly thicken around the middle as they age, and mature trees can come in all different shapes and sizes.

Competition from other trees, soils, droughts, floods, and the rhythm of the seasons all have an impact on growth rates, with wet years encouraging increasing tree dimensions.

Tree size, together with its dominance and spacing in the landscape, bushfire, pests and diseases are also factors in tree growth.

River red gums often regenerate as a dense thicket of seedlings after flood, or wet conditions, and it can take years for a dominant stem to emerge. The mature tree can then suppress regeneration and growth of nearby seedlings by leaching tannins from their leaves, which is known as an allelopathic effect.

The Bilston Tree is commonly claimed to have germinated in 1200 AD making it now 824 years old. This is more than double the estimate made in 1963 when the tree was purchased. The first suggestion of such a remarkable increase in antiquity seems to have been made in a newspaper article (thought to be from 1971), but it’s unclear where the enhanced statistic came from.

But estimating the growth rate and age of trees, particularly old river red gums, which often have a large hollow in the centre, and are sitting out exposed in a paddock, can be a notoriously fraught process, so even the initial 400-year-old claim must be an educated guess at best.

Roger Edwards, a Forest Officer at Cavendish, measured the growth of river red gums in the nearby Woohlpooer State Forest over a 25-year period from 1977 to 2002. The trees probably originated as natural regeneration after grazing ceased in 1913 and the block was acquired by the Forests Commission. The trees were thought to be between 75-110 years old at the completion of his trial. Four of his one-hectare plots had been thinned. Roger found diameter growth rates were highly variable and ranged from nearly zero to 0.6 cm per year, but with an average of 0.26 cm per year. And unsurprisingly, he found that larger, well-spaced trees grew faster than smaller and more crowded ones.

Whereas, I have measured the diameter growth of young, well-spaced, 23-year-old river red gums, near a creek at 2.3 cm/year. Trees planted on farms, with access to ground water, well-spaced and initially well-fertilised also show high growth rates.

So, in June 2024, I decided to practice a bit of field forestry and measure the Bilston Tree for myself with a trusty tape and clinometer, and then compare its size to other records.

But if you look at the attached table I have compiled, there are some odd contradictions and discrepancies for the tree’s dimensions, particularly for 1961, 1987 and 2013. It’s also hard to know what techniques may have been used to measure the tree in the past, or if a standard breast height of 1.3m for diameter was adopted.

For the purposes of this exercise, I have considered the 1971, 1998, 2011 and 2024 measurements to be the most reliable.

If you look at the increase in diameter using the measurements from 1971 to 2024, the Bilston Tree grew a total of 27 cm over the 53-year period. This equates to an annual diameter increment of 0.51 cm/year. That’s the equivalent of a single annual growth ring (or end grain) being only 2.5 mm wide which, as any wood turner will tell you, seems reasonable for red gum timber .

The 26-year period from 1998 to 2024 equates to an increase in diameter of 13 cm, or 0.50 cm/year.

And it’s a very similar story for the more recent 9-year period from 2011 to 2024 which equates to 0.55 cm/year.

So, if we assume an average diameter increment of 0.5 cm per year over its life, and then working backwards, the Bilston Tree might now be more modest 516 years old. (258 cm ÷ 0.5).

However, if we use a lower growth estimate of 0.26 cm/year, based on those trees measured by Roger Edwards at Woohlpooer, it could be nearly 1000 years old (which seems very high).

I accept there are lots of assumptions and flaws with this method, but without cutting it down and counting the rings, or taking core samples, it’s impossible to be 100% certain.

The crown is thinning and showing signs of senescence while there is some epicormic growth from the lower trunk. Unlike many other old river red gums, there is no major swelling at the base or large burls. Large branches fell in 1973 and again in 2013 which may partly explain its shrinking stature over the decades.

I understand a core test showed in 1987 that the trunk was solid. The large branch which broke from the tree in 2013 has been carved by local artists.

The carpark, walking track, interpretive signs and surroundings all looked well-loved and carefully maintained. Although, some of the information on the interpretive sign about the Bilston Tree is contradictory and would benefit from a review. The magnificent carvings on the fallen branches had been freshly coated with preservative. Full credit must go to the local DEECA staff and the adjoining landowner for taking care of this arboreal treasure.

The Bilston Tree may not be the world’s largest or oldest river red gum as is often claimed in the tourist brochures. And maybe it doesn’t really matter because it’s still big, still old, still magnificent and still well worth the visit.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bilston_Tree

Forests Commission Files – 73/1299 & 61/888. “Reprieve for a giant red gum at Wattleglen, Parish of Warrock, Brimboal [Bilston’s Tree], Casterton Forest District”. Held at Public Record Office Victoria (PROV).

Main Photo: Bilston Tree – Feb 1964. Photo: Gregor Wallace.