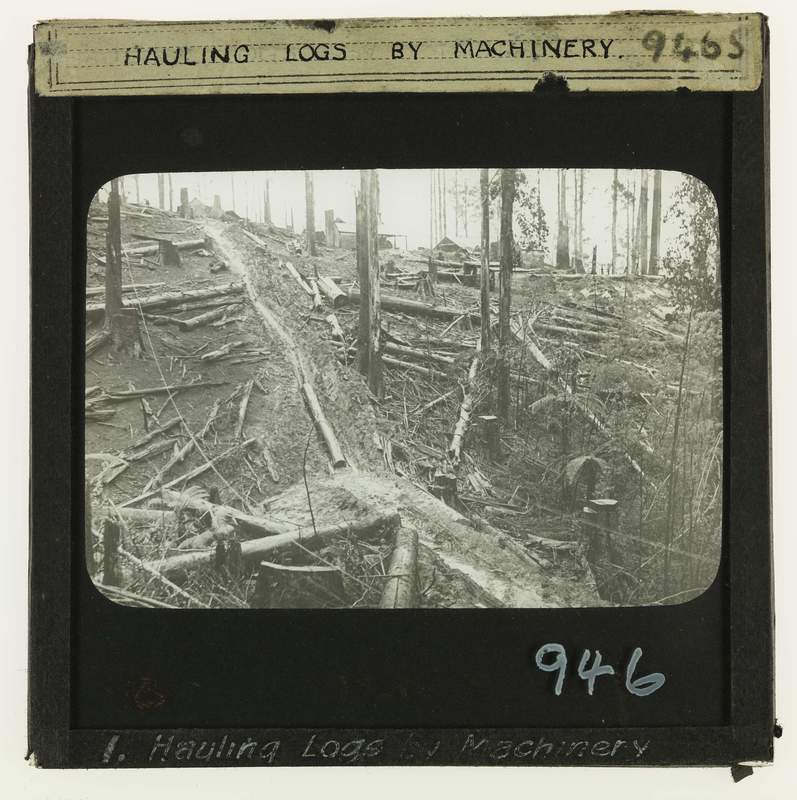

Logging in rough and steep country had always presented serious challenges to contractors and sawmillers. In addition to the obvious safety considerations, delays caused by terrain or weather had impacts on operating costs and ensuring smooth wood flows to the sawmill.

In 1936, Erica District Forester, Arch Shillinglaw, gave an account in the Victorian Foresters Journal about skyline and high lead logging operations by notable local sawmiller Jack Ezard.

Ezards operated a number of mills and timber tramlines in the wet mountain forests along the length of the Thomson catchment. They had previously owned and operated sawmills in the Warburton area from 1907, before shifting to Central Gippsland in 1932, and later to Swifts Creek in about 1950.

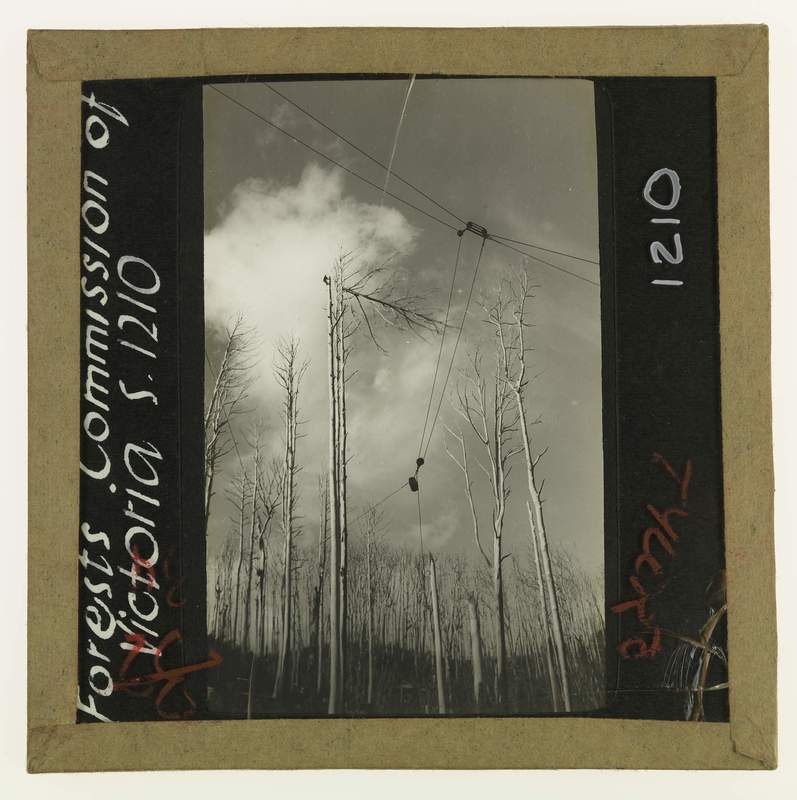

Ground snigging of logs had serious disadvantages at these higher elevations in the Thomson Catchment. The bush was also studded by massive granite boulders and traversed by steep rocky creeks. It often snowed in winter and, other than the timber tramways operated by the company, there were very few roads.

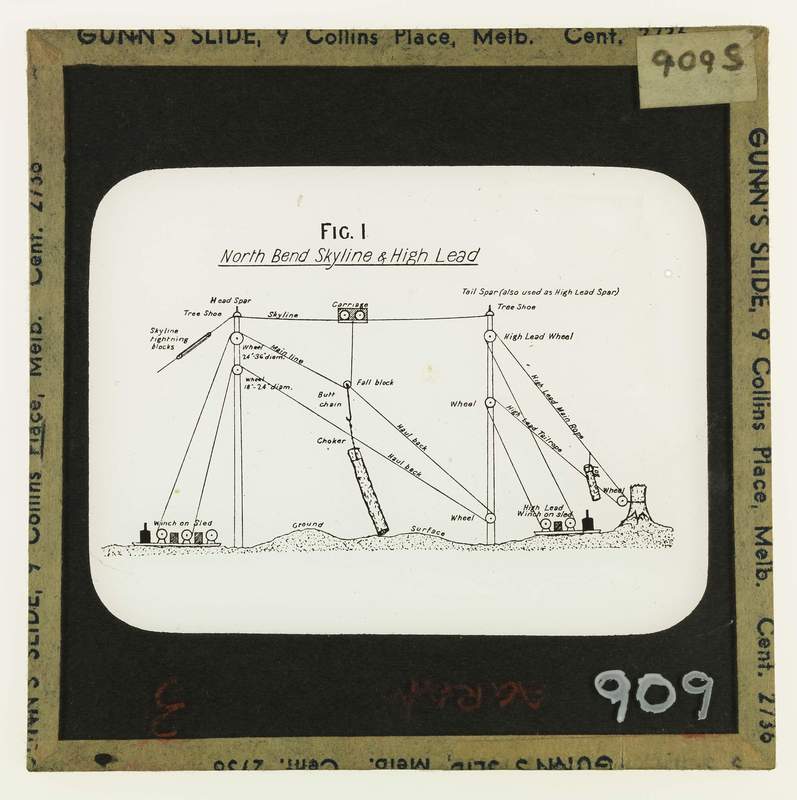

To overcome the steep and difficult logging conditions Ezards purchased an American North Bend Skyline System.

The system was first introduced into the Pacific Northwest by the North Bend Lumber Company based in Washington in 1912 and consisted of a number of key elements.

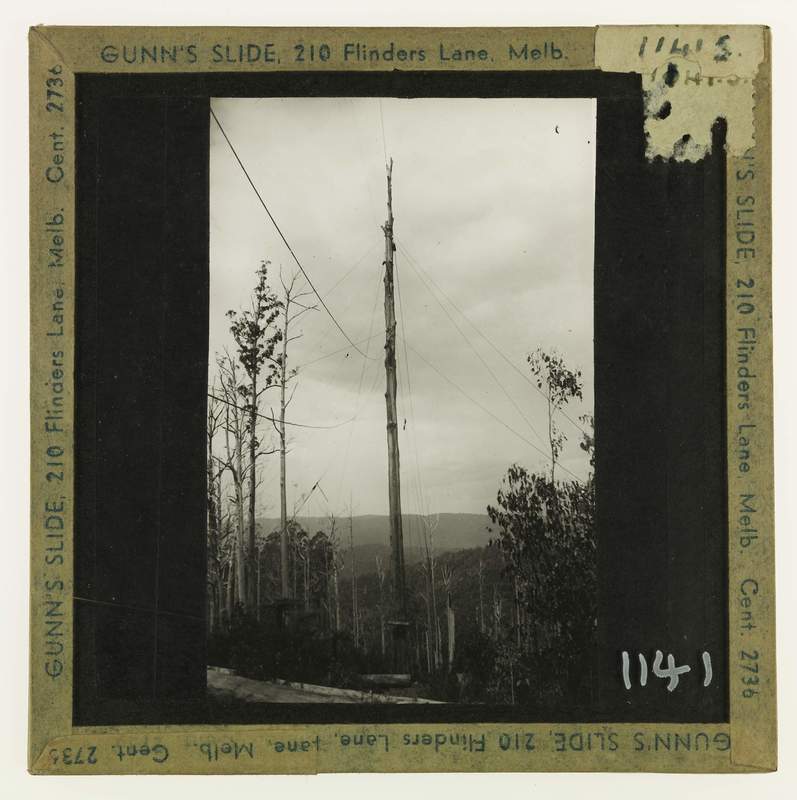

Head and tail spar trees, preferably 200 feet or taller in height, and placed any distance apart to a maximum of 2,500 feet. The spar trees were supported by several stay wires.

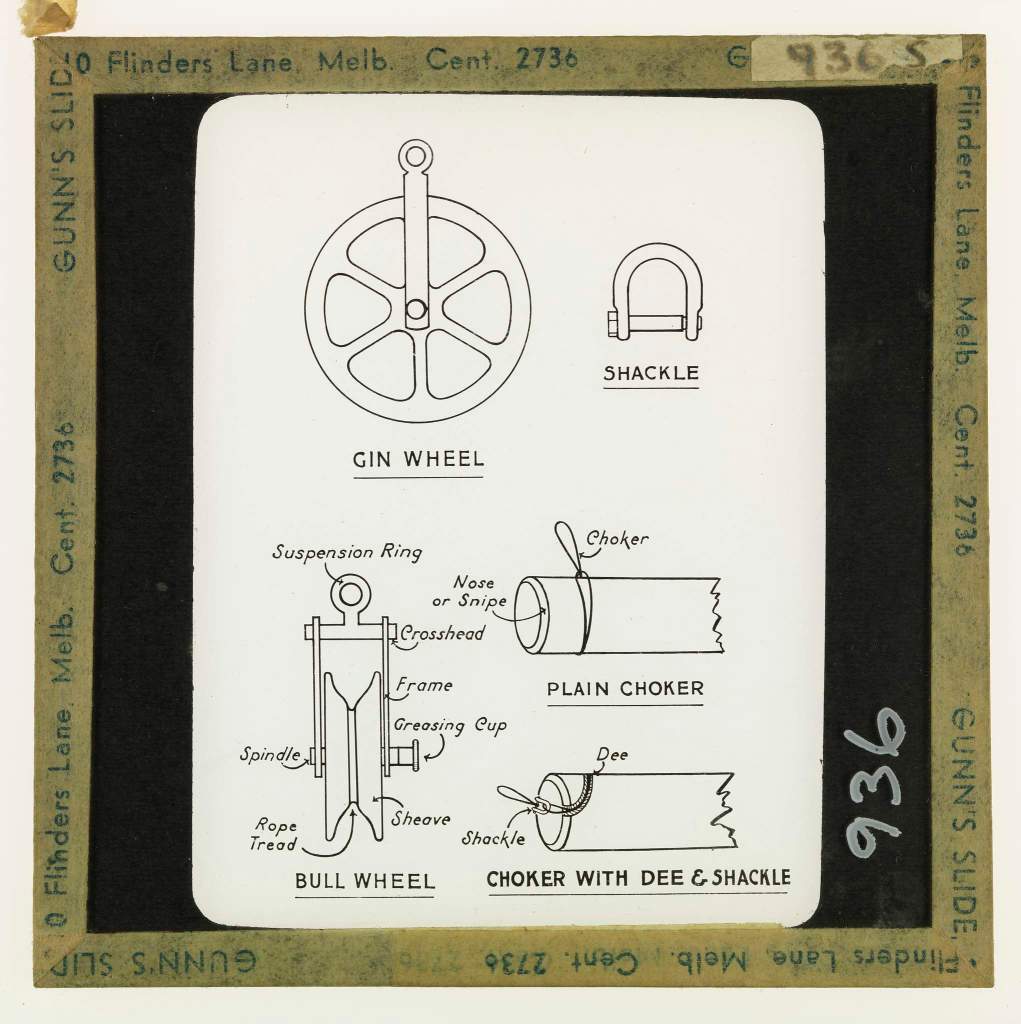

The skyline is a wire rope of about 1 ½ to 2 inches in diameter, passing over a tree shoe at the top of each spar then tightened and fixed at each end. A sag of 5% deflection was allowed to prevent undue strain and breakage of the wire.

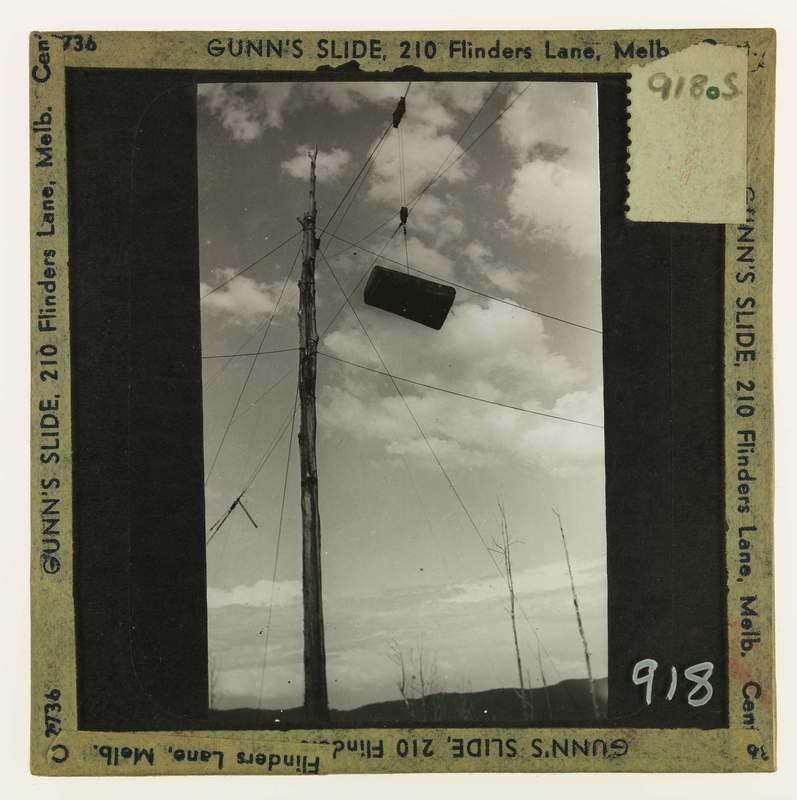

The steel carriage, measuring 4’6” x 2’6” and weighing 7 hundredweight (360 kg) fits over the skyline and runs along on two wheels.

The main line is a wire rope 1 inch in diameter with one end attached to the steel carriage and passing down through a fall block and then over the high lead wheel near the top of the head spar and then to a which drum.

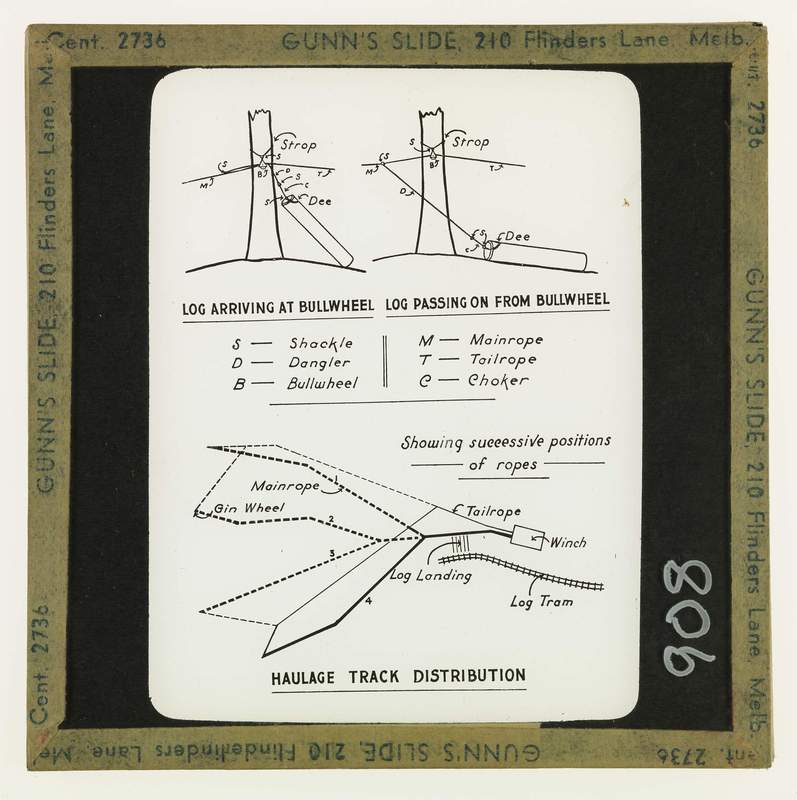

The haul back, or tail rope, is a smaller ½ inch to 5/8-inch diameter wire rope attached to the fall block and then passing over a wheel at the base of the tail spar, then back over another wheel on the head spar before making its way to the winch drum.

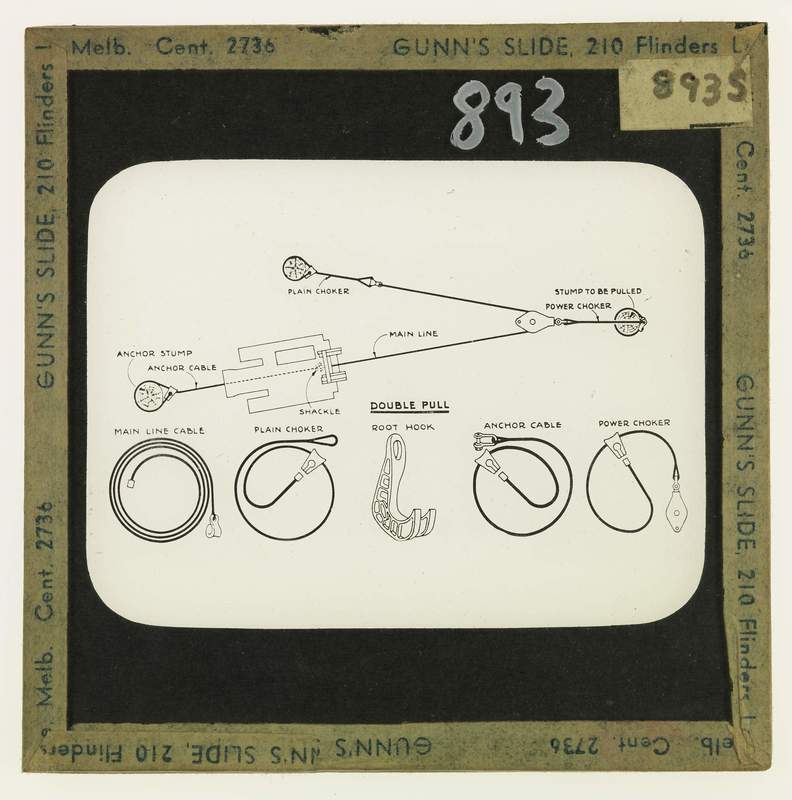

A butt chain is attached to the fall block and to a “chocker” – a wire rope for gripping the log.

The steam winch at the head spar sits on a timber sled to enable movement. It has 10 inch by 12 inch cylinders or greater and operates at 140-200 pounds of stem pressure. If it is a “friction machine” it has two drums for logging (main and tail rope drums) and one drum for loading. If it is a geared machine and additional engine is needed for loading.

The skyline system can log a strip up to five chains wide either side of it. It also lifts logs completely off the ground, or with just the tail dragging. Logs can be brought in much faster than with ground haulage and can straddle streams and go over large rocks.

Once logs arrive at the head spar, they are loaded onto rail trucks by the winch or by tractors.

High lead systems have a slightly different arrangement with the main rope from the winch drum passing over the high lead wheel at the top of the tail spar. The rope then leads off into the bush and is tied to a stump. The rope moves in an arc to another stump as the coupe progresses.

A high lead system can gather up and yard logs to the tail spar over a radius of about 2,000 feet, depending on the height of the spar and the nature of the terrain.

Working in conjunction, a skyline and high lead system, can potentially log over 500 acres.

It’s thought the last steam driven high lead logging operation in Victoria was the Washington Winch near Swifts Creek. It was also operated by Ezards as late as 1960-61.