In about 1900, experiments were conducted in England by Mr William Powell to perfect a new process of preserving wood.

Mr Powell, who owned a sugar refinery in Liverpool, had noticed that the wooden staves supporting the vats on the side where the molasses was spilt lasted longer than those untouched by the solution.

Pondering the reason, he decided that sugar must have some durable effect on the wood, and by experiment gradually evolved the powellising process.

William Powell took out patents in 1904 for his new timber preservation process and companies were formed to exploit his idea around the globe.

The process was very simple. Timber was first cut to size such as sleepers or floorboards and then stacked onto small rail trucks which were run into large iron tanks about 15 ft high and 25 ft deep and then made watertight.

A thin syrup of molasses and other chemicals was poured into the tanks until the stack of wood was completely immersed. Arsenic was added as a preservative against termites.

Brought to boiling point by steam passing through pipes the solution was kept at high temperature for about three hours, or longer depending on the size of the timber, and then allowed to cool.

After about 24 hours the process was complete, and the solution was drained off. The treated timber was then taken out and placed into drying kilns where it was kept for about 12 days. Sleepers were not dried in the kiln but were stacked wet.

It was claimed that the Powellising process could convert both hardwoods and softwoods into nonporous, homogenous timber that was harder, stronger and tougher than the timber in its original state. It was also claimed the treated timber would resist dry rot and termites.

In Australia, the process was first demonstrated in 1905 at a small plant near Perth. The Western Australian State Government then contracted the company in 1908 to supply 230,000 treated jarrah railway sleepers for the Port Hedland – Marble Bar railway.

A plant was also built in Sydney and Powellised timber was used for telegraph poles for the NSW railways, flooring for the Sydney Harbour Trust and wooden blocks for paving the streets of Sydney.

In January 1911, the NSW company wrote to the Victorian Conservator of Forests, Hugh Mackay, seeking details of timber royalty charges and information about the availability of mountain ash forests in the Upper Yarra and Neerim districts.

The Managing Director of the NSW parent company, John Rose Gorton, (father of future Prime Minister, John Grey Gorton) applied for a permit in July 1911 and the proposal was submitted to State Cabinet for consideration. After some due diligence and checking on the financial status of the company, an offer was made in September 1911 for two, 1,000 acre cutting areas with a further 2,000 acres in reserve.

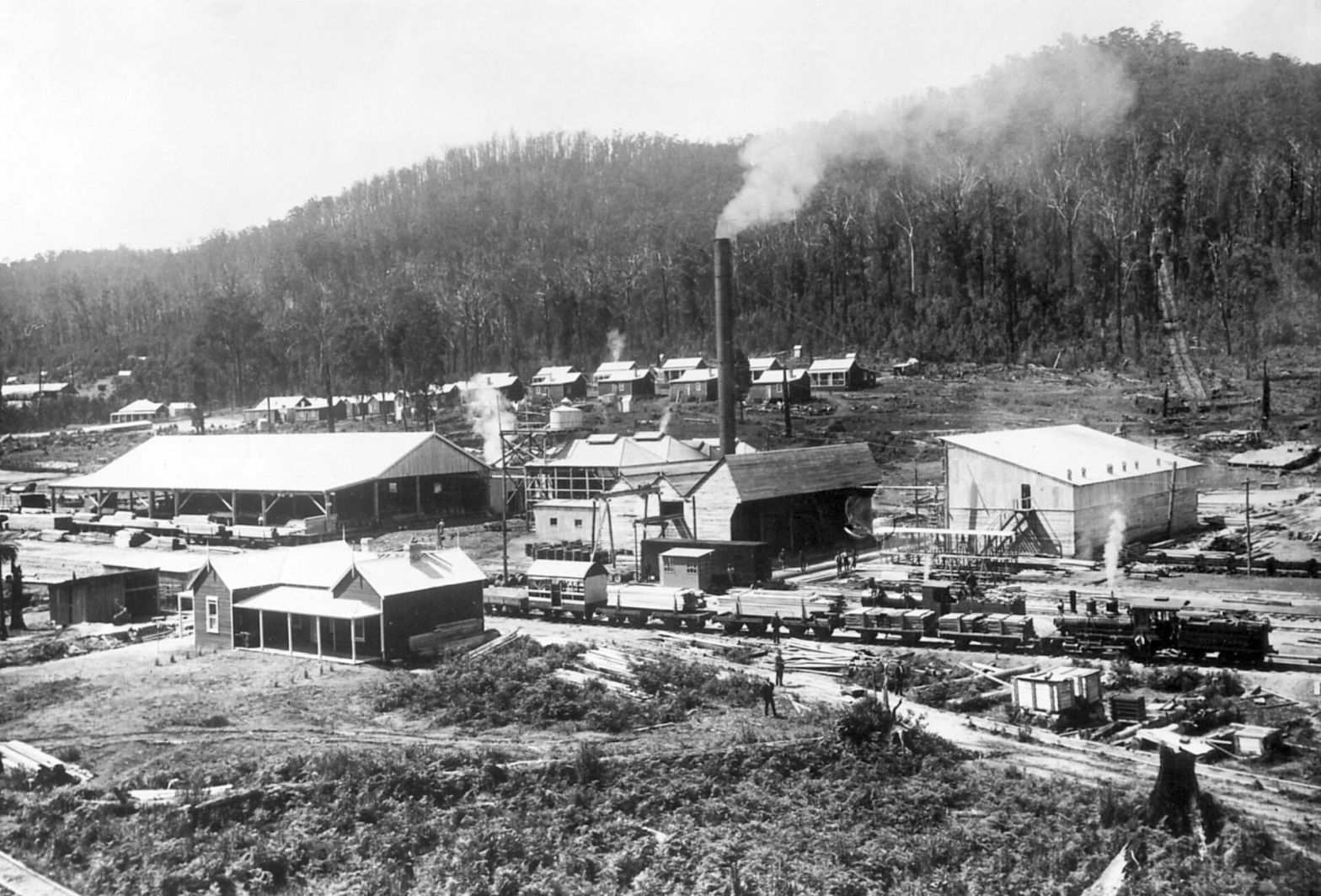

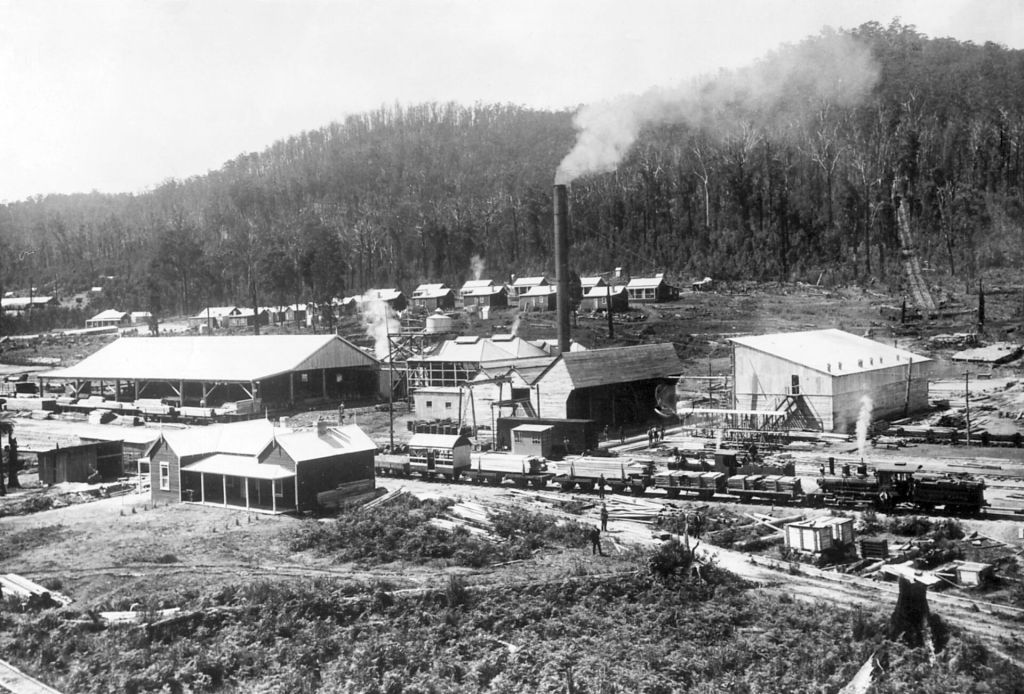

In 1912, the Victorian Powell Wood Process Limited (VPWPL) was established, and during its first year of operations work proceeded rapidly on the construction of a sawmill and timber processing works at Powelltown.

To support the mill the company built a town around it, and to provide transport, it built a 3 ft gauge tramway, some 11 miles long from Yarra Junction.

It’s a long story, but it was called a “tramway” for legal purposes. An Act of Parliament was needed to build a railway, something not easy for a private company to achieve. The Yarra Shire, and not all the locals were entirely pleased about a private line either and would have preferred a Victorian Railways one.

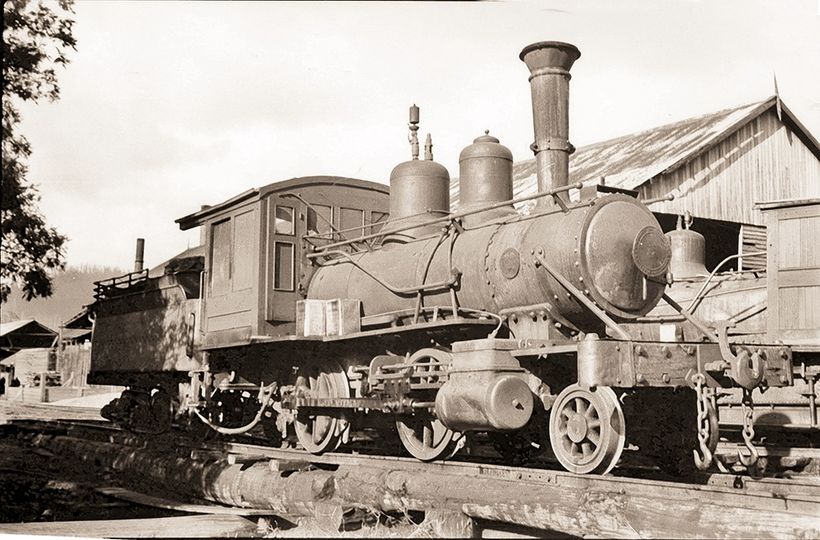

And even before any rails had been laid, a Baldwin 2-4-0 steam locomotive, “Little Yarra”, arrived in Yarra Junction. The line to Powelltown was in operation by May 1913 carrying machinery to the new mill site.

The Powelltown tramway was unique in providing a passenger service and it also carried goods for farmers along the Little Yarra valley. The service continued until the construction of an all-weather road to Powelltown in the late 1920s.

Beyond Powelltown the company built a further two miles of tramway into the bush to access its log supply. This network was progressively extended over the subsequent decades and serviced many small sawmills in the bush.

However, the company was a financial failure and only operated for one year. It had secured a lucrative contract to supply 100,000 Powellised sleepers to the Trans-Australian Railway, then under construction to link South Australia with Western Australia. But of the first delivery of 6000 sleepers, only 500 were accepted, and only nine met the contract specification. The sleepers were cracked and distorted in shape. It was thought that the drying process and sap replacement had damaged the timber. Not surprisingly the contract was cancelled.

This was not the only example of the failure of Powellised timber. A Royal Commission was held by the Commonwealth Government into the fiasco, but the WA Government was uncooperative and refused to give evidence. The Commission heard damming testimony that Powellised sleepers in NSW had been a failure as early as 1909. It was the same story in New Zealand where 66% of the powellised softwood sleepers had to be removed within two years.

Just why the company went ahead in 1911 with such a huge investment at Powelltown after the inconclusive results in WA and NSW remains a mystery. But by September 1915 the company had folded with huge losses.

The site at Powelltown then reverted to a sawmill which was operated successfully for many years by the Victorian Hardwood Company.

Ref: Stamford, F. E, Stuckey E.G., and Maynard, G L. (1984). Powelltown. Light Railways Research Society.

http://media.lrrsa.org.au/ptc/Powelltown_Tramway_Centenary_spreads.pdf

Photo: J L Buckland