Melbourne grew rapidly after the 1851 gold rush and struggled to maintain adequate water supplies and sewerage disposal.

All the night soil, trade waste, as well as waste from kitchens and homes was just thrown into open channels in the street and it simply flowed wherever gravity took it… mostly into the Yarra River. The problem got so bad that some British journalists unkindly described the city as ‘Smellbourne’.

In response, the Yan Yean reservoir was built on the Plenty River in 1857 as Australia’s first water supply reservoir, followed by the Werribee sewage treatment farm in 1897.

But water-borne diseases, particularly cholera, remained fearful killers in cities throughout the nineteenth century. A Royal Commission was established by the Victorian Government in 1880 to address these concerns.

In a bold and visionary political move, large catchments in the Upper Yarra River were vested in the newly established Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) in 1891.

A closed catchment policy was also introduced where timber harvesting, recreation, mining, farming, settlements and all public access was not permitted, mainly as a step against the threat of disease.

The relatively small O’Shannassy watershed was vested in the MMBW in February 1910 and an aqueduct commenced soon after to carry water some 50 miles to the Surrey Hills Reservoir to supply the fast-growing eastern suburbs of Melbourne.

Its sometimes claimed the aqueduct was named after Sir John O’Shanassy, three times Premier of Victoria, although I have my doubts because the spelling is slightly different and the dates don’t align with the period of his reign.

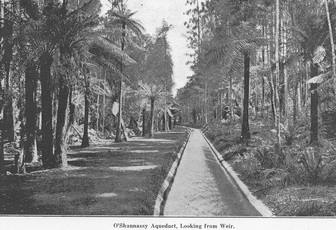

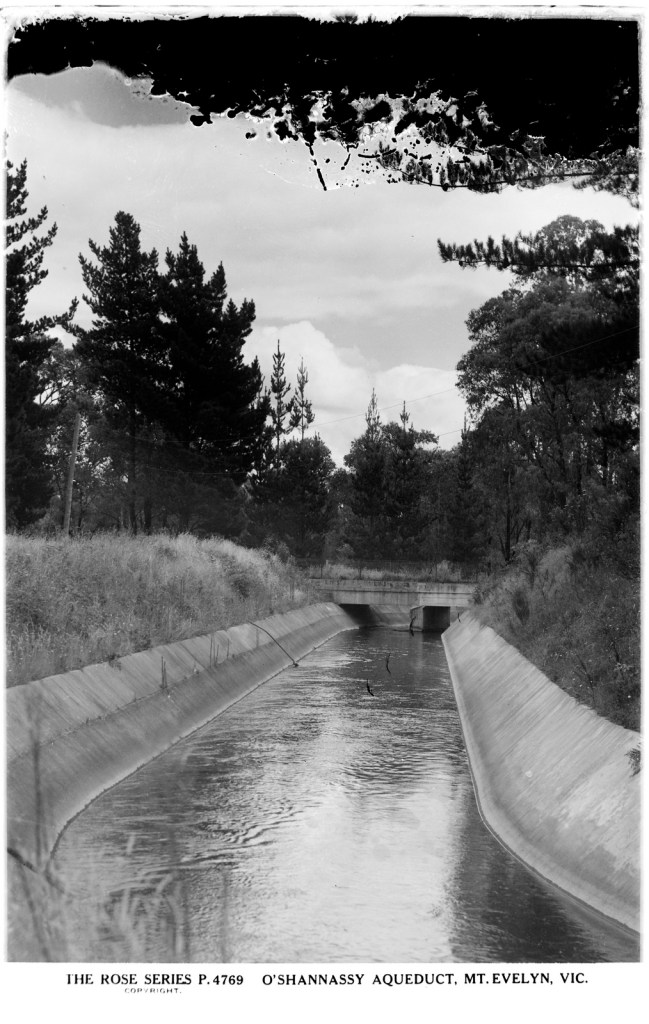

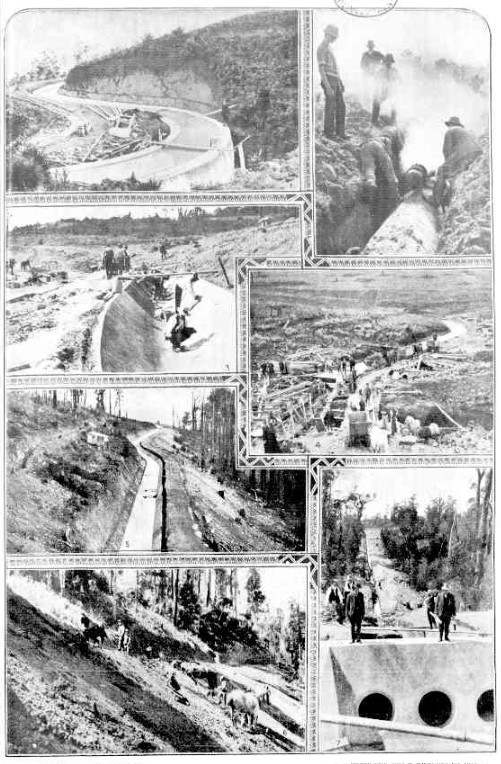

The open concrete channel skirted along the southern slopes of Mount Donna Buang on a constant gradient of 2 feet to the mile and operated completely by gravity.

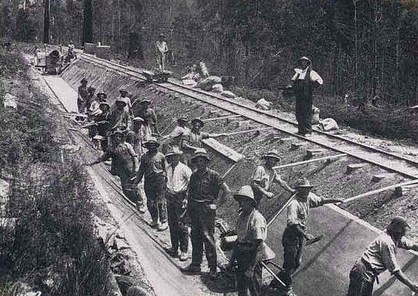

The channel, 9 feet 3 inches wide at the top and 3 feet 4 inches deep, was dug by hand and horse-drawn scoops.

Next to the cement lined channel, a flat access track was constructed from the excavated material with a rail line on top to deliver heavy construction materials like timber, stone, pipes, steel and cement.

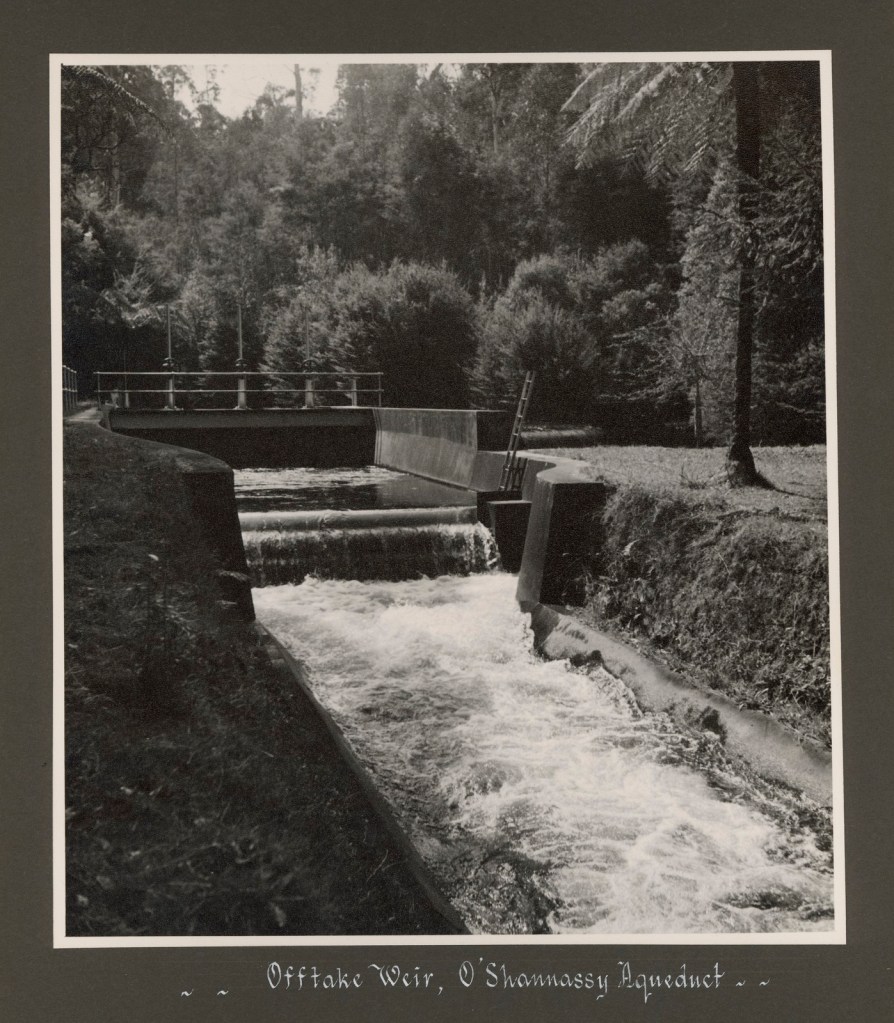

Water was also carried up and down the steeper slopes, across roads, creeks, rivers and through both farmland and residential areas by siphons, pipes and weirs. Some of the pipes were made from timber staves and some from steel.

The total cost of construction of the O’Shannassy aqueduct on its completion in 1914 was £426,890.

But Melbourne’s water supply woes continued and in 1924 the channel was increased in size to 12 feet 11 inches wide and 5 feet 2 inches deep. Its capacity effectively tripled from 20 million to 60 million gallons per day.

The O’Shannassy scheme was augmented in 1929 by a new weir on the Coranderrk Creek near Healesville which diverted water into an aqueduct that joined near Woori Yallock.

Resident caretakers stationed along its length carefully controlled water flows with a series of manually operated locks and gates. They also patrolled the channel to keep it clear of debris and functioning properly.

The next major phase in the O’Shannassy project was the construction of Silvan Dam in the eastern foothills of the Dandenong Ranges. Works began in 1927 and were completed by 1930.

The sumptuous O’Shannassy Lodge was also built near the aqueduct. It was mostly used by the MMBW Commissioners and their guests as a private weekend retreat. The Lodge famously hosted Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip when they visited Melbourne in 1954.

But by the mid-1990s, the ageing aqueduct was nearing the end of its service life. There had been several serious collapses over the years, the main one being at Dee Road above Warburton which placed the town and community at severe risk of flash flooding.

Eventually in December 1996, the open aqueduct was closed and replaced with large underground pipes to carry the water to Silvan.

Today, a 34 km section of the old O’Shannassy aqueduct is a spectacular bushwalking and bike riding route.

https://oshannassyaqueduct.weebly.com/